A Traveller’s Tale: What Does DNA Have to Say About Me?

As an APS Archivist, I’ve had the honor of working with the records of the Society’s Members, such as geneticists Hampton Carson and Barbara McClintock. In light of our Dr. Franklin, Citizen Scientist exhibition, their discoveries piqued my interest in exploring genetic data, albeit on a much more modest scale, in the form of a home DNA kit.

I had a general sense of my family’s background because my father had done some genealogical work in the pre-Internet days. The mix was typical for a midwestern family—German, Celtic, and Scandinavian—but certain threads had been lost over time. We are pretty sure that both sides of the family had been farmers for generations, with Quaker and Anabaptist roots. As genetic testing has become popular, I was curious (like many others) to see what was in my genome.*

When I received my results from Ancestry, the afore-mentioned lineages were confirmed, but I was surprised to find genetic mapping to segments found in the Caucasus region, such as Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. How interesting, I thought. Did I have a Central Asian relative who slipped between the cracks of my father’s research? I did an additional test with Living DNA, which provided genetic mapping to the Pashtun people of Pakistan and northern India. With additional research, I found that testing companies use different datasets; while outlier results reflect a decent guess, they are not always conclusive, and assignments can be updated over time (I have since received another vote for South Asian from GenomeLink). Whoever my ancestor was, they seem to have traveled the Silk Road, picking up DNA along the way.**

Given these results, I was now in the position of going back into genealogical research to figure out the unexpected DNA, as opposed to the science easily confirming my dad’s conclusions. On a fateful day last summer, I signed up for a trial of the extended Ancestry database and started poking around. I did not expect to find her, but there she was: Veronica Dilabaugh/Dellenbach Hershberger (1752?-1791), a possible source—an alternative narrative—who raises even more questions than she answers.

According to the anecdotal evidence I’ve found through genealogical circles, Veronica was “a Gypsy*** girl reared by the Amish.” She was reportedly adopted by the Dilabaughs/Dellenbachs, Swiss farmers who settled in western Pennsylvania. However, the timeline for Veronica’s story in the Ancestry database was confusing, with details that seemed a bit scrambled. I analyzed the documentation and she seems to have been born or adopted in Pennsylvania around 1752, while her adoptive sister Barbara was born in Bern, Switzerland in 1755.

Fortunately, the Head of Manuscripts Processing at APS, Valerie-Anne Lutz, is an expert genealogist (recently elected President of the Pennsylvania Genealogical Society!) and came to my aid. I was grateful for her guidance and glad to find sources in the APS collection to support my genealogical research. For instance, Valerie pointed me towards relevant journals in the Library, such as an article in Pennsylvania Heritage, which confirmed the presence of Romani in the keystone state. Some English sects were deported and/or indentured as servants in colonial America; German-speaking groups also relocated to Pennsylvania in the 1750s. They were referred to as “Black Dutch” or “Chikkeners” (derived from the word “zigeuner,”**** meaning vagabond).

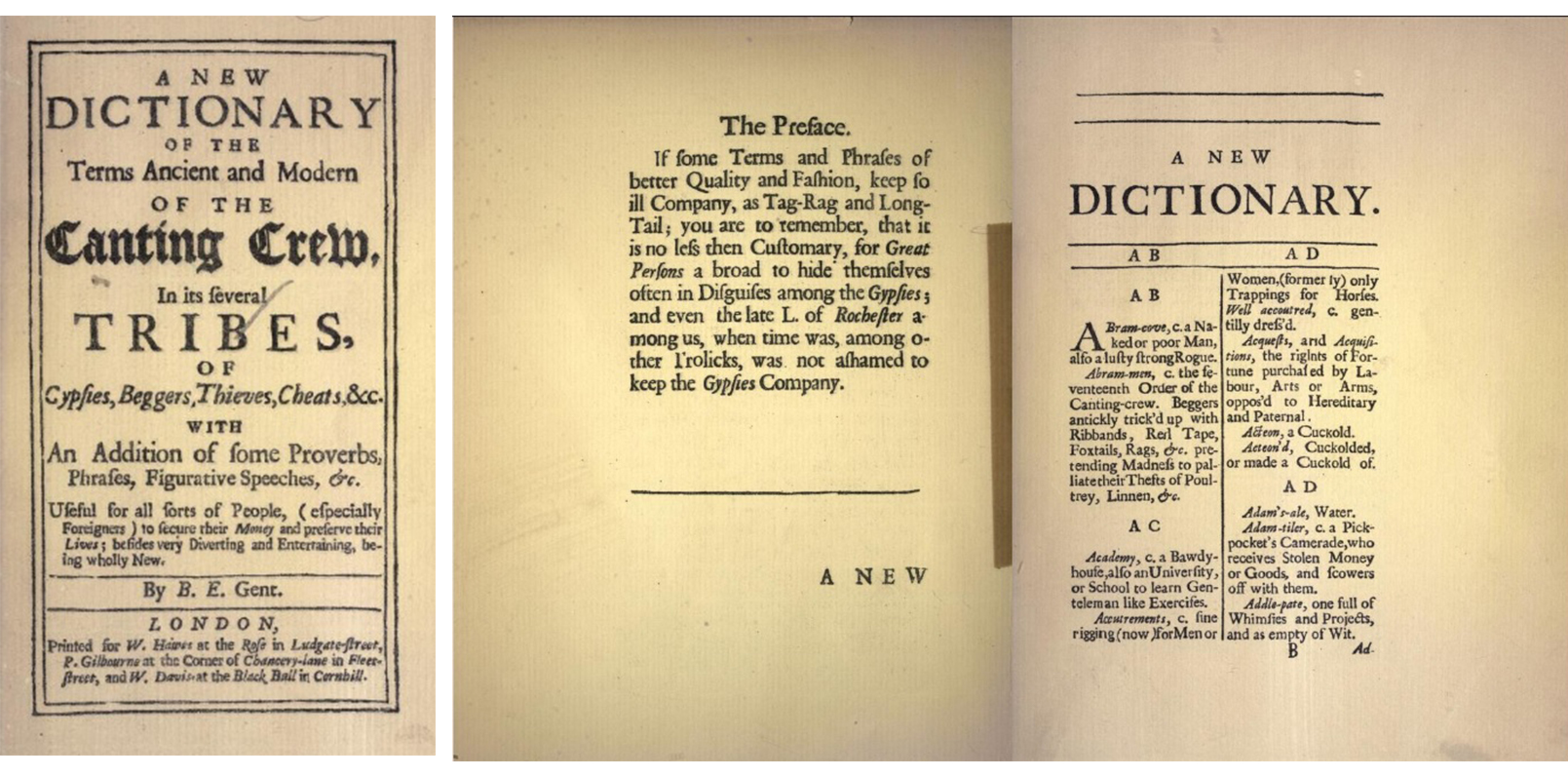

thieves, cheats, &c., with an addition of some proverbs, phrases, figurative speeches, &c., by B. E. Gent [London: Hawes, 19-- (1690)]

Given the linguistic similarity between their German dialects, it was possible for the Chikkeners to communicate with the Amish and do business with them. An early dictionary in the APS collection provides additional phrases by the Romani diaspora, no doubt borne out of the need to adapt and survive in a variety of circumstances (see image above).

I also consulted the Record of Indentures project, looking under traditional Romani occupations such as horse trading, metal smithing, and basket weaving. While I was not able to find conclusive evidence, it is still a good data set to consult for groups who may have been indentured as part of the immigration process, and/or lack documentation in other official records.

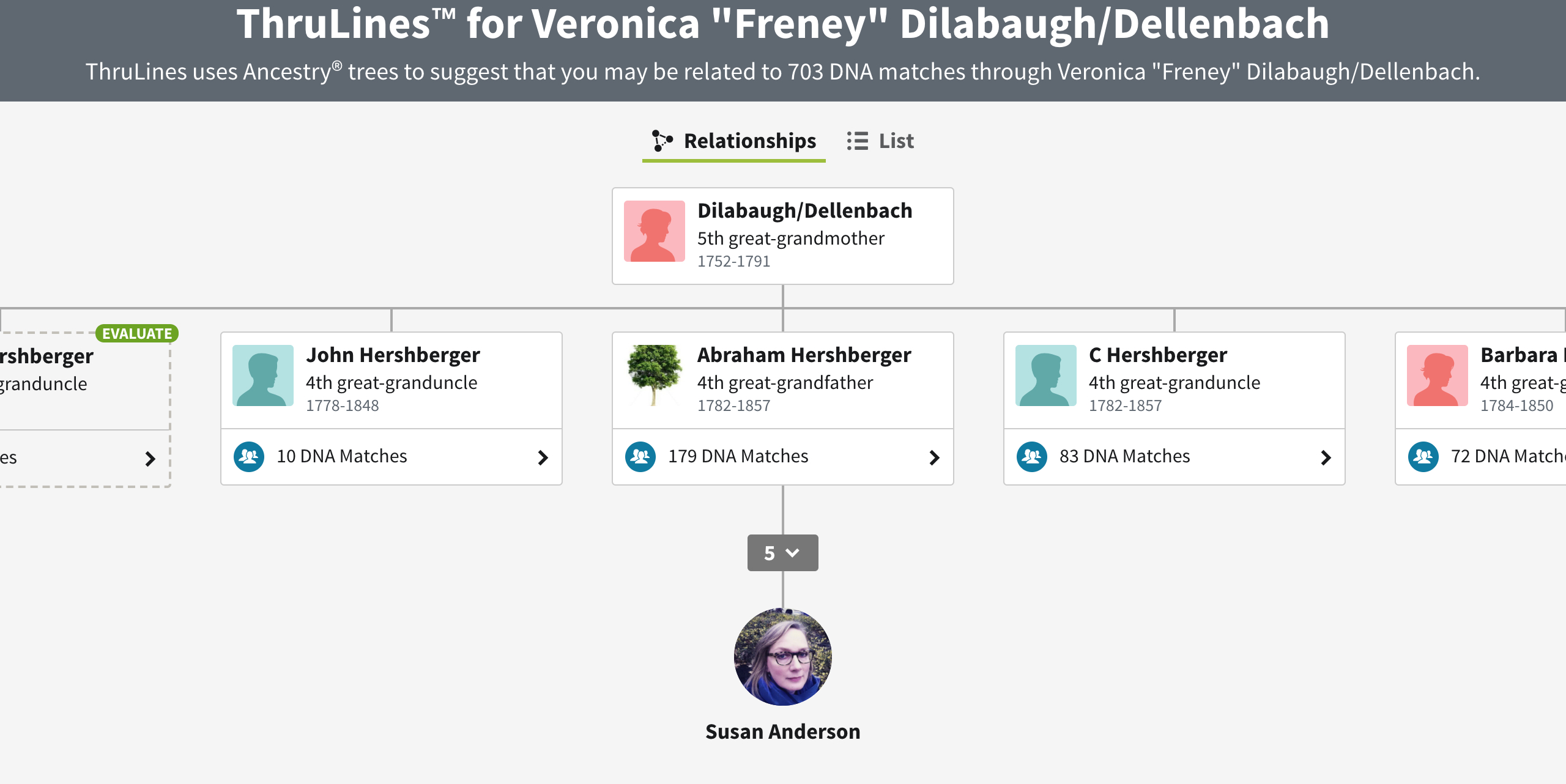

Given these contextual clues, one can see how the Romani had their share of hardship, which may have contributed to a potential adoption. In turn, Jacob and Elsbeth Dilabaugh/Dellenbach raised the child, along with their daughter Barbara, on a farm near Somerset, Pennsylvania. In 1774, Veronica married John Hershberger, an Amish farmer who also lived in the area. The couple had nine children and she passed away in 1791, at the young age of 39. While I haven’t been able to find much else about her, Veronica is noted in her descendants’ documentation in the Lancaster Genealogical Card File. At last count, it’s been estimated that she has hundreds of descendants and is a notable matriarch among Amish “ThruLines” (see image below).

me, as well as DNA matches with other descendants (accessed 6/14/2021; https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-geneticfamily/thrulines/tree/1735588474:9009:66/for/836EB0C2-CE01-4904-9A9C-B9E86478495E)

I’ve learned a lot during this genealogical journey and hope that it might inspire a reader or two to dig into their own past, perhaps even using some of the resources available at the APS!

Header Image: Manuscript Group 213, Postcard Collection, Pennsylvania State Archives

* Thanks to research such as the Humane Genome Project, it has been determined that 99.9% of human DNA is the same. Only a small percentage (.1%) is examined to determine an individual's ancestry.

** Given the scientific evidence that the vast majority of human DNA is the same, ethnicity estimates should be kept in perspective; for further reading, please see Caitlin Harrigton's recent essay, "Your 'Ethnicity Estimate' Doesn't Mean What You Think It Does."

*** Please note: “gypsy” is considered to be an ethnic slur; it’s being used here as a direct quote from the Ancestry database. Preferred terms for this diasporic population include Rom, Roma, Romani, Romnichel, Sinti, Tinkers, Travellers, etc., depending on the subgroup they identify with, mixed race ancestry, and of course individual preference.

**** “Zigeuner'' is considered to be a pejorative term in High German; I’m only using it to explain the etymological relationship to Pennsylvania Dutch (e.g. Deutsche, or German), which was spoken by my ancestors. Perhaps the most troubling application of this status was used by the National Socialist Party; it has been estimated that over 250,000 Romani were killed by Nazi Germany during the Holocaust. The term has also been applied to anyone who could be viewed as an “outsider,” whether it is through a different skin color, ethnicity, religious affiliation, etc.