A Merchant Witness to Revolution: Miers Fisher, Jr. (1786-1813)

Miers Fisher, Jr. (1786-1813) came from a prominent Quaker family. His father Miers, Sr. (1748-1819) was a merchant, lawyer, politician and civic leader. Miers, Sr. took Quaker principles against violence and oath-taking seriously. He was exiled from Philadelphia during the Revolution as one of the notable Virginia Exiles, though his reputation and station quickly recovered after the War.

The portion of the Fisher Family Papers held at the APS includes extensive letters, merchant accounts, meteorological observations, and a detailed diary of Miers, Jr.'s travels. He witnessed the beginning of the Spanish War for Independence against Napoleonic rule in 1808 and wrote about it at length. In 1809, he traveled to Russia and wrote home about his experience and kept a diary. The letters of Miers Jr. describe the economy and culture of Russia, as well as provide Miers's view on America's foreign affairs as an American living in a foreign port. He notes especially the growing rivalry between Great Britain and the United States and the maneuvers of Napoleon.

Miers, Jr. embarked on a career as a merchant. The record of his travels forms the most interesting part of the small collection of Fisher family papers held by the APS. Donated by a Fisher descendant named Elizabeth Cadwalader Wood, the collection contains, among other items, Miers Fisher Jr.'s journal and correspondence. Fisher was a good observer, writing about business conditions, the people and cultures he encountered, American foreign policy, and the overall political situation. What makes the material particularly fascinating is that his adventures took place during the Napoleonic Wars, and he witnessed some key events.

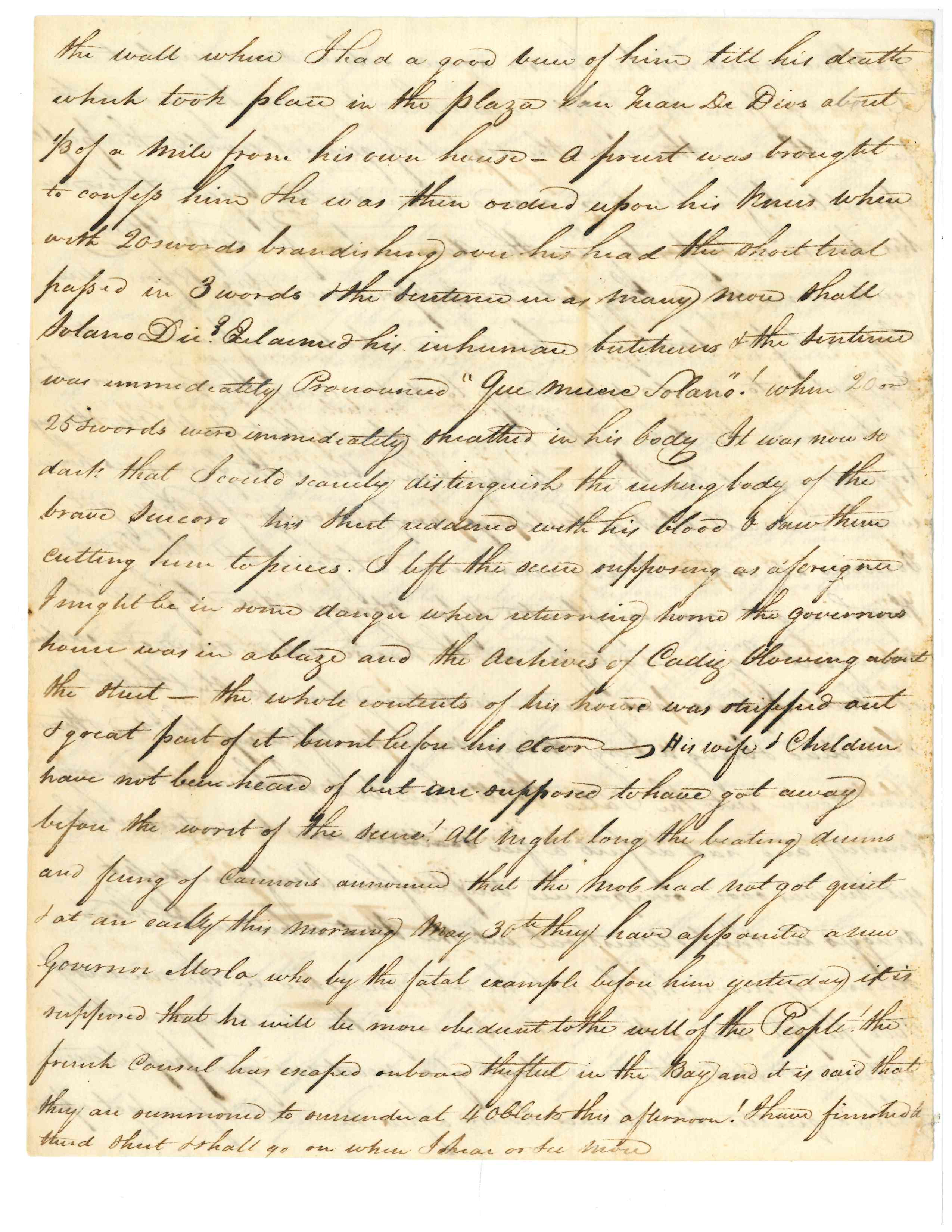

One such event took place in Cádiz, Spain. The anti-French revolution had broken out. Since many elites were pro-French, the revolution started spontaneously among the lower classes. Cádiz itself underwent a rapid shift from acceptance of the French to strong support for the British. Soracco de Solano, the Spanish Governor of Cádiz, thought the British were the true enemies of Spain and misjudged the revolutionary zeal of the populace. In a scene witnessed by Fisher, de Solano was harassed, captured, and killed by a mob. In Fisher’s words, he was judged guilty of:

"inhuman butcheries & the sentence was immediately Pronounced “Que muere Solano!” when 20 or 25 swords were immediately sheathed in his body. It was now so dark that I could scarcely distinguish the reeking body of the brave Succoro[sic] his shirt reddened with his blood & saw them cutting him to pieces."

Fisher eventually left Spain and found further adventures in Russia. On his way to St. Petersburg, privateers captured his ship near Norway, where he was held until an indemnity was paid. Later, while visiting the Russian capital, he met John Quincy Adams, the newly arrived American minister, the first to the country. Fisher would occasionally socialize with Adams over the next four years.

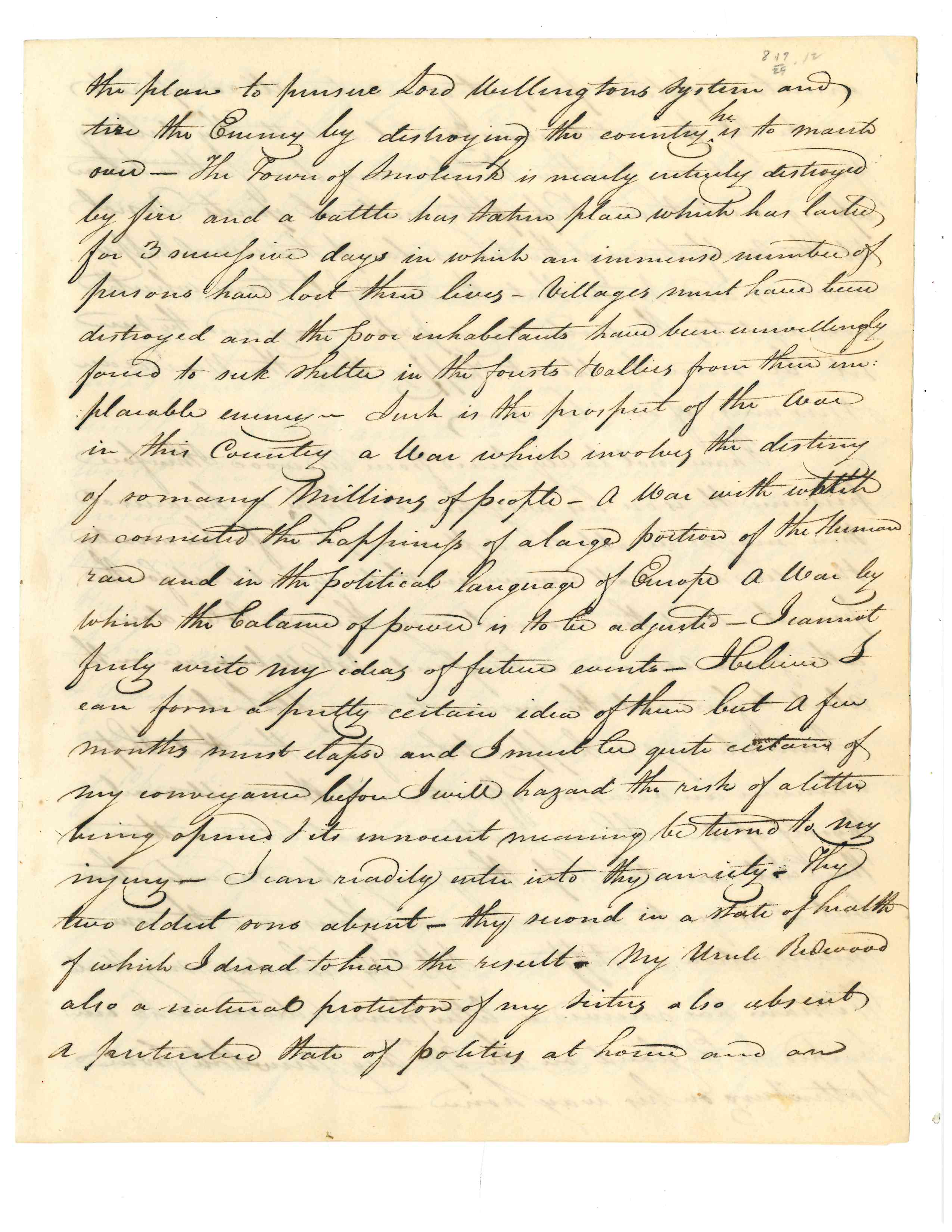

In 1812, one of the most momentous events in 19th-century Europe occurred: Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. Fisher wrote about the French crossing into Russia from the Polish border and then of the Battle of Smolensk, the first major engagement of the invasion. The city was “nearly entirely destroyed.” “An immense number of persons have lost their lives,” he wrote, “villages must have been destroyed and the poor inhabitants have been unwillingly forced to seek shelter in the forests and vallies [sic] from their implacable enemy.” In his letters, Fisher was careful to show respect for the Tsar and did not express what he thought would happen, as he “must be quite certain of my conveyance [for the letter] before I will hazard the risk of a letter being opened & its innocent meaning be turned to my injury.”

He did continue to write some, consistently anti-French correspondence, complementing the Tsar and praising the fortitude of the Russians. Bias aside, he accurately portrayed the situation, which ended with French forces retreating from Moscow. Fisher unfortunately did not live to see the final defeat of Napoleon. He died in Russia in 1813, having witnessed great events in his short life.

Header image: Image of Miers Fisher. Jr., found in Nina N. Bashkina and David F. Task, eds., The United States and Russia: 1765-1815. US Department of State, GPO, 1980, p. 626.