Making a Menagerie: Following Animals in the 13th Earl of Derby Papers

Header image: Banded Mongoose, Plate 5, from John Edward Gray, Gleanings from the Menagerie and Aviary at Knowsley Hall (1846-1850), Biodiversity Heritage Library.

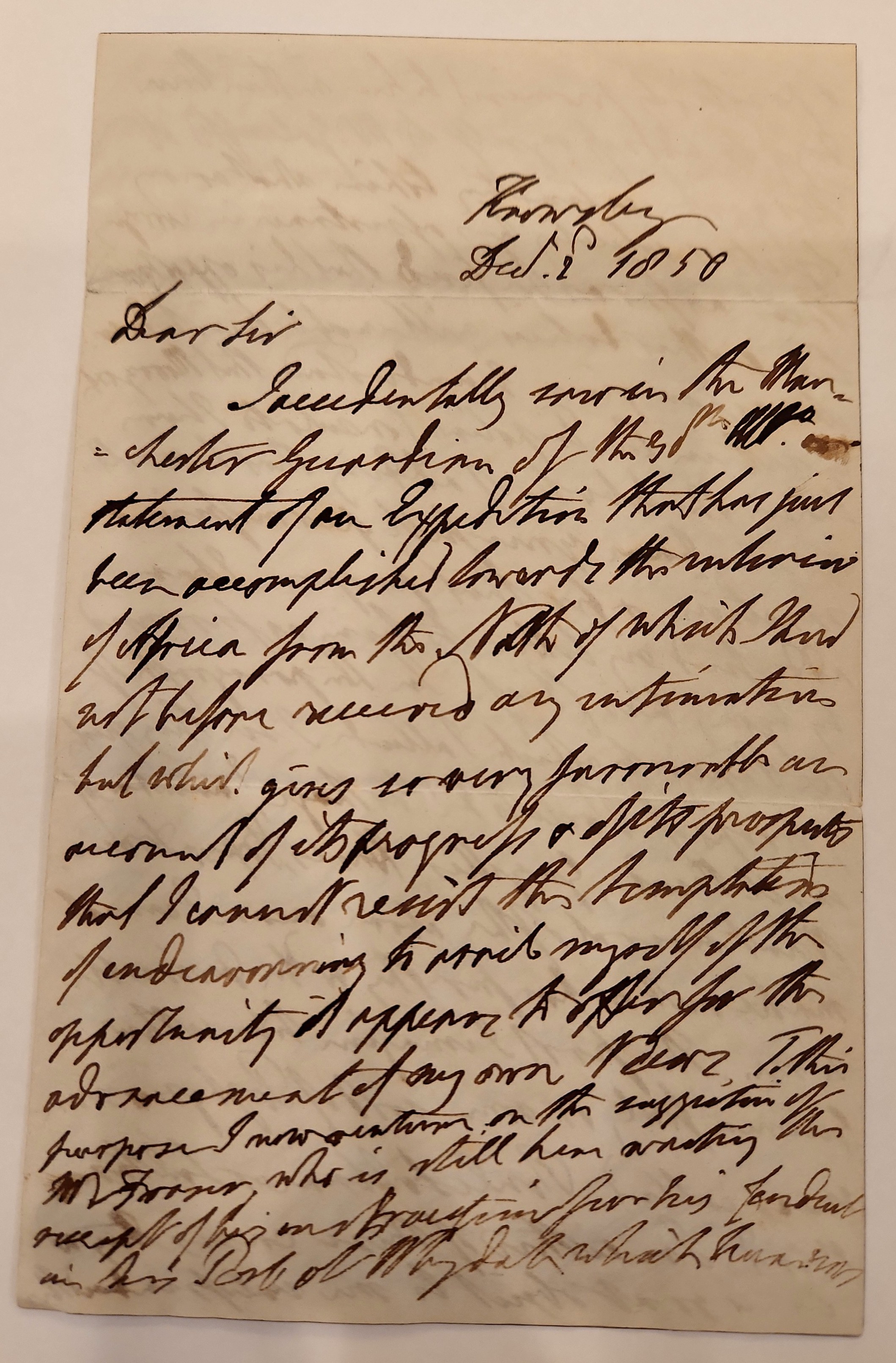

Edward Smith-Stanley stumbled across the news. Perusing the Manchester Guardian in 1850, he spotted a lengthy report of “an Expedition that has just been accomplished towards the interior of Africa from the North.” The journey had taken Heinrich Barth and James Richardson from Tripoli to as far south as Lake Chad, carrying the interests of the British and Prussian governments with them. Exploration offered Richardson new understandings of the North African slave trade, provided Barth with knowledge of Sudanic languages and cultures, and presented the British government with a valuable asset: information. Records of topography, language, and resources acted as vital intelligence, part of imperial knowledge-gathering that made land-grabbing and commercial exploitation possible. For Smith-Stanley, the 13th Earl of Derby, the article revealed new commodities within reach: animals yet to be transported, studied, and “discovered.”

From his Knowsley Hall estate, Smith-Stanley used his wealth, power, and connections to establish one of the largest animal collections in 19th-century Europe. His letters, housed at the American Philosophical Society, offer a rare glimpse into the formation of zoological collections within the British Empire. The bulk of the correspondence is addressed to Richard Reade, the British Consul at Tripoli, who fulfilled the earl’s desires for zebras, flamingos, and other African animals. In return, Smith-Stanley offered money and political favor, ensuring that Reade and his family received favorable consular appointments across North Africa.

Upon news of the expedition, Smith-Stanley wrote to Reade with his latest instructions: to contact Frederick Warrington, the son of the late consul-general at Tripoli, who “possesses so decidedly powerful and expansive an influence over all the tribes of the Arabs that I feel certain, if he would only be so kind as to say the word, my objects would be…effectively carried out.” Behind the confidence of consuls and military officials, the stocking of the Knowsley menagerie rested upon Indigenous knowledge and non-European labor. These contributions appear between the lines of Smith-Stanley’s correspondence, mentioned only occasionally in practical discussions of capture and infrastructure. When searching for animal care in Tunis, the Earl advised asking “Cloacho Bogo, a Carpenter,” who was “conversant with our scientific names and…particularly well in the Arab language.” More often, however, letters speak of captures and discoveries with little regard for the people behind them.

More broadly, the Earl of Derby’s letters highlight the unique challenges of transporting living animals across the globe. The stuffed, pinned, and preserved specimens of Enlightenment natural history had allowed Britons to protect their expertise and reduce risk. My dissertation, The Living Animal, explores how efforts to capture, nurture, and display living animals from across the British Empire necessitated new systems of colonial infrastructure and knowledge gathering.

For the Earl, postal networks and steamships revolutionized his ability to communicate and move animals quickly, reducing climactic shock. The expansion of British interests into Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa also put new species within imperial reach, such as fennec foxes, banded mongooses, and ostriches. Even so, the animal trade was risky business. On November 20, 1850, Smith-Stanley received word that his agent at Southampton had received “a box, which, I am sorry to say, contained not the living Fennec but its dead body.” The earl made “the best of a bad bargain,” mounting the fox’s skin and bones before restarting his efforts to obtain and breed the living thing.

By the time of his death in 1851, the Earl had accumulated a living collection of 1,272 birds and 345 mammals; along the way, his museum collection had grown to over 20,000 specimens—often by-products of his failed attempts to commodify and reproduce the living. You can still see many of those 19th-century inhabitants at Liverpool Museum today. While at Knowsley, visitors can now drive among zebras and ostriches at its “African Savannah zone.” You still won’t be able to see a fennec fox, but the Earl of Derby Papers reveal the origins, costs, and labor behind making that British savannah a reality.