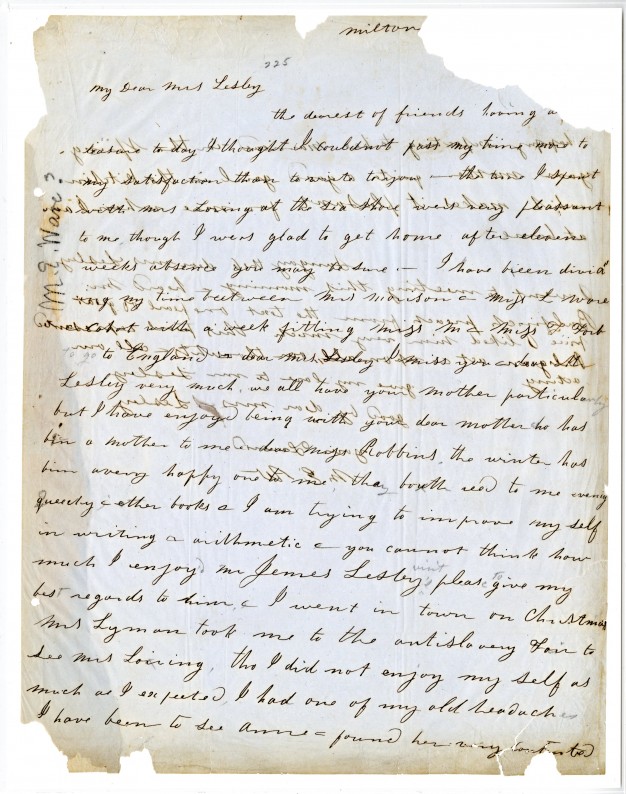

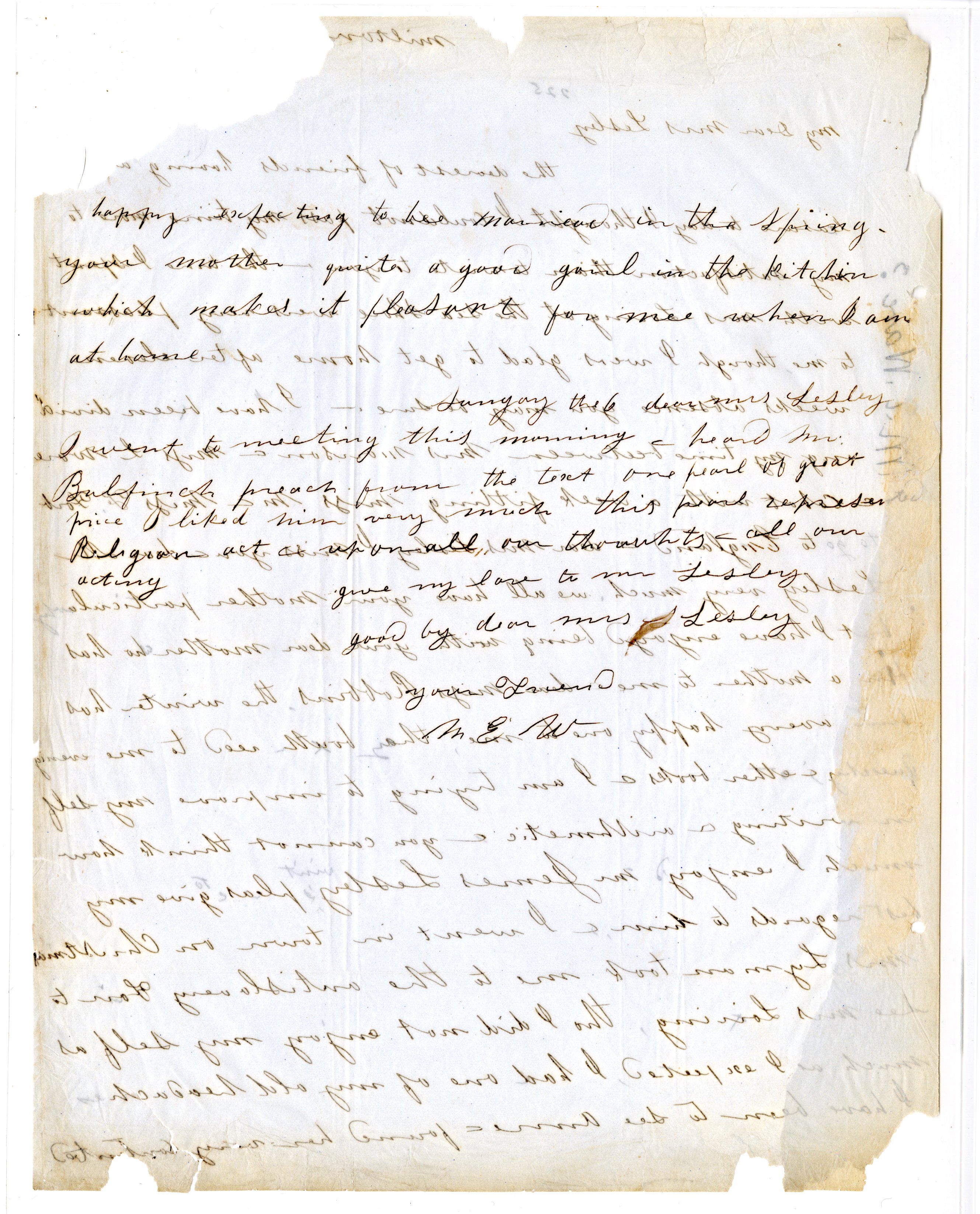

Letter from Mary Walker to Susan Lesley, undated

As the voices of people who were enslaved are too often lost to time, historians and archivists strive to locate every letter and reference and make them available. The Library & Museum of the American Philosophical Society counts among its more significant items a letter from Mary Walker, a formerly enslaved woman who escaped slavery and befriended minister and geologist J. Peter Lesley (APS 1856) and his wife Susan Inches Lyman Lesley. This letter to Susan Lesley is a friendly update on Mary’s life.

Mary was raised within the household of her enslaver Duncan Cameron in North Carolina, where she spent time with his daughters, attending their lessons and learning to read and write. During an 1848 trip to Philadelphia, she and Cameron had an argument. As retaliation, he planned to send her to another enslaver in the Deep South, a threat that kept too many women enslaved, for fear of separation from their children. With the impending forced choice between enslaved or free, but separated from her children either way, she escaped to freedom.

She became acquainted with the Lesleys, who used their network of abolitionist friends to try to rescue her children. Mary’s son Frank escaped after Cameron died in 1853, but sadly she never saw him again. She tried to get her other children back from the Camerons, but could not. When the Civil War ended, a Union official went to the Cameron house to tell her two remaining children, Bryant and Agnes, that they were free, after which they reunited with their mother.

In the letter, Mary Walker mentions how much she misses the Lesleys and how she spent the day with Susan Lesley’s mother. She also mentions that “Mr. Lyman” (likely a relative of Susan’s) took her to the “anti-slavery fair” to see Mrs. Loring, although she did not enjoy it as much as expected due to a headache. She did, however, enjoy the preaching of “Mr. Bulfinch,” possibly Unitarian minister Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

The letter was apparently written during Mary’s early years of freedom and prior to her reunification with her children, as the anti-slavery fairs were held yearly from 1840 to 1855 in Brookline. “Mrs. Loring” is likely Louisa Gilman Loring, the wife of attorney, abolitionist, and philanthropist Ellis Gray Loring. The Lorings lived in Brookline and were active in the movement there. Their home was a center for abolitionists and for sheltering people who had escaped slavery.

Mary Walker was close with the Lesley family; the Lesleys named their daughter Mary Lesley (later Mary Lesley Ames) after her. She remained close with the family even after their move to Philadelphia, as evidenced by their references to her in correspondence. Mary continued to live in Cambridge and in 1870 lived with her daughter Agnes and Agnes’ husband James Burguwyn, a carpenter.

Mary’s son Bryant married Ann Garie, an Irish immigrant, in 1866 in Lynn, Massachusetts. By 1870 Bryant and Ann were living in Cambridge, Massachusetts with their children Edward, Frederick, and John, all born in Massachusetts, and Bryant was working as a gardener. The Walkers had three more children: Mary, born in 1870 and named for her grandmother; William, born in 1873; and Hannah, born about 1875. In 1880 Bryant continued to work as a gardener while Ann did washing and ironing work.

Only three letters from Mary have been found, according to Sydney Nathans, author of Free A Family: The Journey of Mary Walker (Harvard University Press, 2013). Mary is mentioned in letters, including one from Frederick Douglass to Susan Lesley, within the J. Peter Lesley Papers (acquired from Charles Ames, a Lesley descendant, in 1942) and in the Chauncey Wright Papers at APS. The bulk of material about Mary Walker, however, is found within the hundreds of letters and diary entries about her in the Ames Family Historical Collection at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute.

Nathans uncovered Mary’s story as part of a larger project on the enslaved people of the Duncan Cameron estate and their descendants. Nathans consulted the Lesley Papers and a dozen other collections of the Lesleys’ antislavery friends and associates along with the Cameron Papers at the Southern Historical Association and the extensive Ames Family Historical Collection. He presented his work in a talk to the Friends of the APS in 2012.

While finding information about enslaved and formerly enslaved people can be challenging, the story of Mary Walker and her family and Sydney Nathans’ research provides an example of how one may find them in the papers of enslavers, abolitionists, and other people with whom they may have been associated and bring their stories to life.