Documenting the Development of Banking in Early America: Charts and Pamphlets

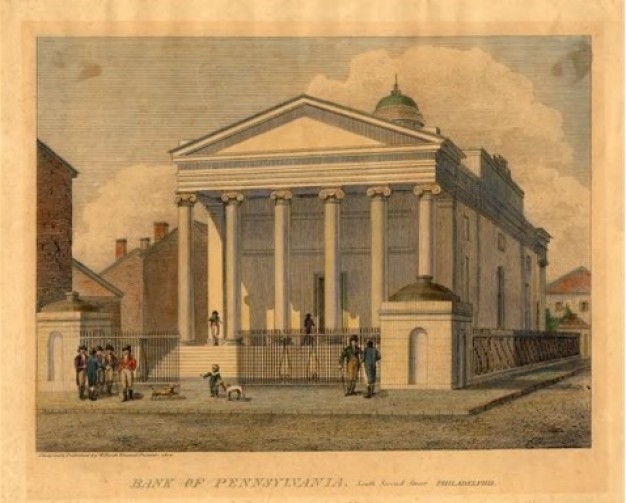

Header Image: Bank of Pennsylvania, South Second Street, Philadelphia, William Russell Birch, 1804. Print engraving. American Philosophical Society (APS).

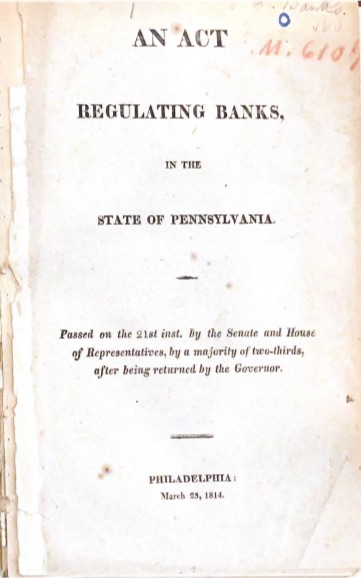

While banking was new in the Philadelphia area in the 1780s (the Bank of North America started its operations in 1782), it developed progressively over the next two decades with the creation of several institutions like the Bank of Pennsylvania. W. R. Birch’s engraving from 1804, pictured above, shows that these banks were mostly carrying the business of wealthy, urban merchants. However, this situation was altered after the Act Regulating Banks in the State of Pennsylvania was passed in 1814. It allowed for the creation of more than 20 new banks in the state, especially in rural areas. The American Philosophical Society (APS) holds a very rich collection of pamphlets that illuminate the way banks were perceived in the early republic. They allowed me to see how debates between those who supported banks and those who opposed them were articulated. Banking advocates saw these institutions as a necessary tool for economic prosperity while opponents feared the value of paper-money might collapse at any moment.

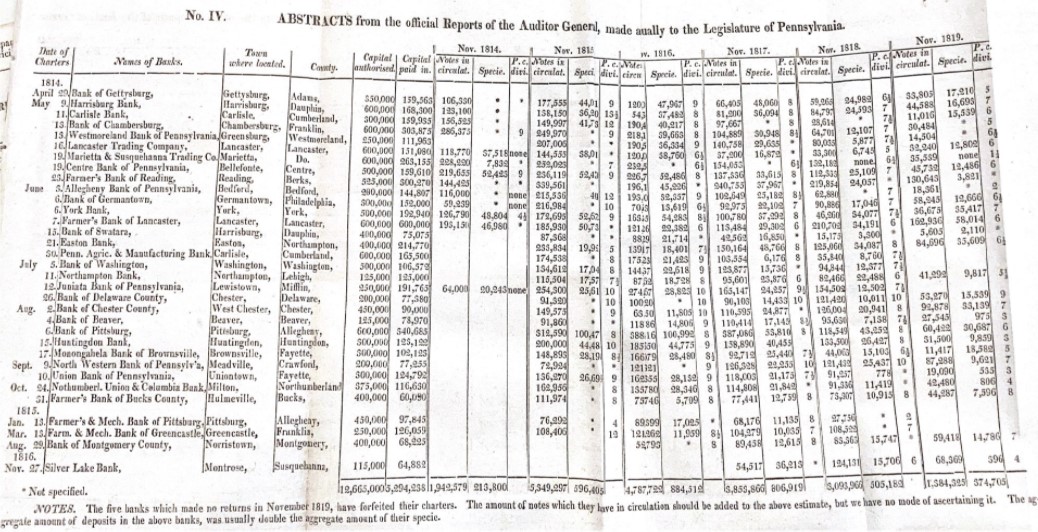

This increase in bank openings led to the creation of tools states used to monitor their activity. The document below is a synthesis of yearly bank reports that were merged into a single chart to help determine the causes of the financial panic of 1819. One of the main causes that people focused on was banknote emissions that many feared were too large, leading to the depreciation of money and a widespread crisis of credit, commerce, and production. Bank reports allowed for this kind of analysis since they recorded both the amounts of banknotes emitted and the amount of specie (gold or silver that seem to have been lacking, according to many Americans’ complaints) held in each bank’s vault. This kind of document also showed how fast banking institutions spread in Pennsylvania. This is not a surprise, since many texts from the early years of the 19th century show that rural Americans wanted banks to open closer to them in order to facilitate their business. For instance, a column was published in the Lancaster Journal on the 21st of April, 1810 titled “The farmers of Lancaster County are rich and honest: they are able to support a bank and they ought not be denied a bank.”

The appetite for banking in rural areas was a real deal, and it was supported by several publications like Petlatiah Webster’s Essay on Credit, in which the Doctrine of Banks is Considered: and Some Remarks Are Made on the Present State of the Bank of North America (1786). Interestingly, pamphlets on banks articulated a political dimension—discussing what the authors felt banking policy should be—with a theoretical approach on economics. In his Paragraphs on Banks (1810), Erick Bollmann develops a striking metaphor in which all banks form a system. He writes, “the banks appear to me like a fleet, buoyed up by confidence and credit gliding down the spacious stream of trade and prosperity, each just comfortably ballasted with specie, and all of them linked together by a mighty chain of debtors and creditors, fastened to that ballast.”

In these few lines, the author suggests that banks are interconnected, forming a sort of network (even if he does not use this term). He insists on the importance of specie to back banknotes and prevent a fall of value for paper-money. This image of interconnected banks also bears the idea that the failure of one of them could endanger a whole economy. In Bollmann’s view, banks are necessary for prosperity and should be developed, but their development, if too widespread or poorly monitored, could lead to a major collapse.