ᏃᎵᏍᎬ ᎪᏪᎶᏗ CNAIR ᎢᏗᎦᎸᎳᏗ: ᏩᏕ ᏌᎻ ᏥᎨᏒ ᎠᎾᏥ ᎠᏣᎳᎩᏃ ᎪᎯᏳᏅᎯ

CNAIR Stories: Watt Sam as Natchez Cherokee Collaborator

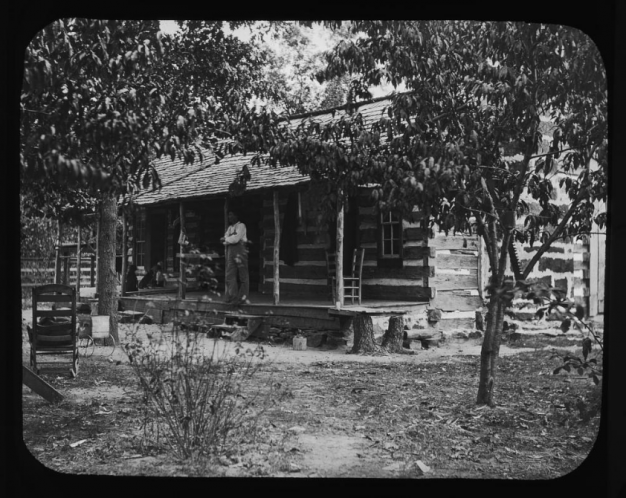

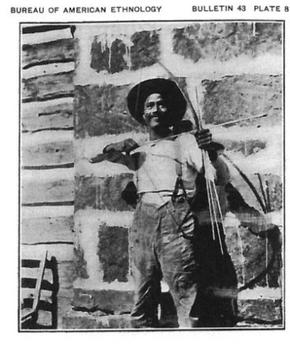

Header image: Watt Sam on his Porch. Lantern Slide by John Reed Swanton. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

As a Summer Intern for the Native American Scholars Initiative deciding on a project that I’d devote seven weeks to researching initially sounded like a daunting task, but it didn’t take long for me to find something interesting in the Digital Collections at the APS. I discovered a mislabeled story that was presumed to be Natchez, told by Watt Sam Jigesv (ᏥᎨᏒ Jigesv is an honorific word in Cherokee ᏣᎳᎩ ᎠᏬᏂᏍᎪᎢ denoting that someone has passed on, used particularly with elders) in the Floyd Glenn Lounsbury Collection of recordings that piqued my interest. Not only was it a Cherokee story, “The Rabbit Dines the Bear,” but it was told in Cherokee. This brought to my attention the interconnectedness of Southeastern Indigenous American peoples. Watt Sam lived in a world often depicted as several separate worlds by academics.

I reviewed the Mary R. Haas Collection for information on Watt Sam. His knowledge was invaluable in numerous ways and the time that he and Mary Haas worked together was critical in cataloging the Natchez language as Watt Sam and Nancy Raven (See Geoffrey Kimball’s The Woman Who Was a Fox) were the last 1st language speakers of Natchez that could still speak fluently.

Watt Sam was born October 6th 1876, presumably in the Cherokee Nation, to Natchez Cherokee ceremonial leader Creek Sam and Eliza Scott, also Natchez Cherokee. He grew up in and around Gore, Oklahoma. Gore is on the border of Muscogee and Cherokee land; Cherokee Nation’s capital, Tahlequah is just Northeast and two prominent Ceremonial Grounds are both within 10 miles. As a young person, Watt Sam was surrounded by prominent ceremonial leaders, and grew up with several of whom would become some of the most well known spiritual revivalists of the Southeastern Ceremonial tradition. Two of these are Pig “Redbird” Smith, adopted brother, and White Tobacco Sam, older brother and eventual chief of Medicine Springs Ceremonial Grounds, the sole Natchez Ceremonial Grounds at the time. He dwelled within the worlds of the Muscogee people and the ᎩᏚᏩ Keetoowah Cherokee traditionalists, fluent in their languages and well versed in their stories, clan structure, and ceremonial beliefs. Watt Sam became a ceremonial leader, serving as the “Head Medicine Maker,” of Medicine Springs, but I suspect he danced all over Eastern Oklahoma. You can listen to him singing in the APS digital collections.

Watt stayed in Eastern Oklahoma all his life and passed in July 1944. In Watt’s lifetime, he saw the Dawes Commission come and force Indigenous people to sign rosters, the implementation of land allotment, and the abolishment of tribal governments. Within his community he saw Redbird split from the Four Mothers society that Medicine Springs continued to maintain, and try to lead the ᎩᏚᏩ Keetoowah down a separate spiritual revival. It was during this time that the cultural survival of all Southeastern peoples was not guaranteed and this uncertainty can be seen in a speech that Watt personally requested Haas to record (Field Notebooks #9. Pp 183-186). Through these era Watt worked with several anthropologists such as John Reed Swanton, whom Watt told stories to, and Victor Riste whom Watt sang and danced with. Only later in life did Watt Sam work with Mary Haas (starting 1933). His intention to work with these linguists and anthropologists was not done without thought. It is because of his work that Watt Sam’s grandnephew, Keetoowah and Natchez cultural revivalist, Archie Sam, discovered Watt’s recordings them to revive several songs and dances that I myself participated in back home at ᏌᎶᎵ ᎤᎾᏓᏢ ᏂᎦᏘᏲ Saloli Unadatlv Nigatiyo Squirrel Ridge Ceremonial Grounds.

When I returned to Oklahoma for a short break this summer I was able to attend the Southeastern Ceremonial tradition of Greencorn and meet with Hutke Fields, the Great Sun of Natchez Nation. In the midst of talking about Watt Sam, Hutke pointed to a couple of his grandkids. They are direct descendents of Watt Sam. When I looked at Jaslyn and Leo it reminded me of the lasting effects of our actions. Hutke is applying for a grant to revive the Natchez language, through the compilation of language resources, with the preliminary goal to digitize the APS collection’s Natchez language material, including over 8,000 lexical files that would not be possible without Watt Sam’s commitment to the language and to Mary Haas.