Richard Shryock’s Vision for the History of Science at the APS

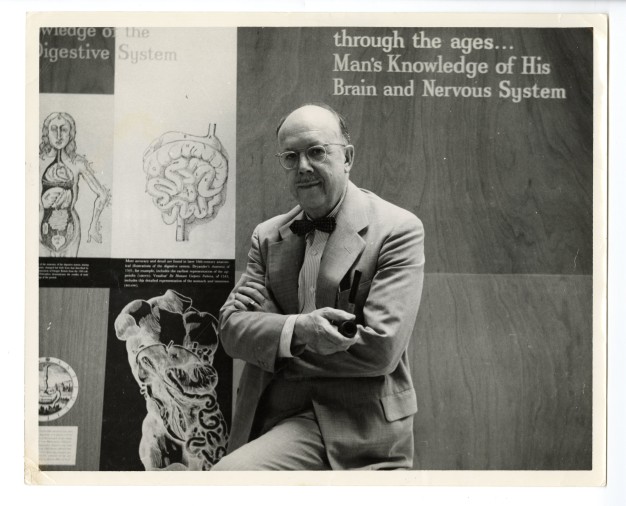

Richard Harrison Shryock, circa 1957. APS.

I’ll admit it: over the past few years, I’ve become more than a little obsessed with Richard Shryock (APS 1944). While some may recognize the name thanks to the American Association for the History of Medicine (AAHM)’s annual “Shryock Medal”, few seem to know about his contributions to the fields of both history of science and medicine, despite his terms as president of both AAHM (1946-1947) and the History of Science Society (1941-1942). Fewer still are aware of Shryock’s role as Librarian of the American Philosophical Society, a position he held at the end of his career from 1959 to 1966.

Born in Philadelphia in 1893, from an early age Richard Harrison Shryock had hoped to study medicine and become a physician; however, following the death of his father and its impact on the family’s finances, he instead became a teacher. He eventually earned a Ph.D. in American History from the University of Pennsylvania following a short stint serving in the U.S. Army’s Field Ambulance Corps during World War I. It was at Penn that Shryock's interest in the history of medicine took shape; yet, while he had hoped to write his doctoral dissertation on the history of American public health, his advisor rejected his proposal on the grounds that while “an interesting subject” it was “not history.”

Shryock would, despite this discouragement, go on to write and publish widely in the history of American medicine, covering topics such as the history of nursing, 18th-century medicine, and the role of quantification in the medical sciences, among others. But his experiences as a nascent historian of medicine at a moment when the field was not yet fully legible to most general historians would come to inform his efforts to professionalize the history of science and medicine for the rest of his life.

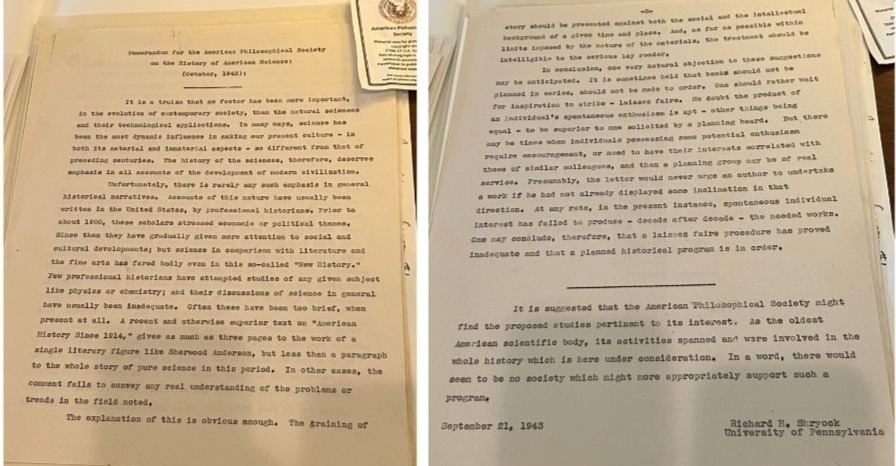

In 1943, as part of his election as a soon-to-be Member of the American Philosophical Society, Shryock delivered a short talk at the Society’s annual fall meeting in which he outlined his vision for the history of science. He emphasized the field’s importance for helping to make sense of modern society and argued that science ought to receive the same level of historical attention as subjects like politics and economics. In his view, one of the barriers preventing more thorough engagement with the history of science had to do with the question of expertise: were historians proficient enough to grasp the more technical aspects of scientific work in their writing? And, similarly, could scientists appreciate the broader intellectual and social contexts in which they conducted research and drew their conclusions?

For Shryock, the solution to this problem lay in bridging the two perspectives. As he put it in the talk he gave to the APS in 1943 on the subject:

“If a chemist or biologist essays to write the history of his field, he needs historical training, just as a historian who wishes to deal with the same theme requires some degree of technical understanding. There is no need to decide which of these two types employs the best approach–the scientist or the historian. It may be that, in terms of their respective backgrounds, the scientist will be at his best in relatively technical accounts, the professional historian in the broader or more generalized interpretations. But there is work aplenty for both, and cooperation is clearly indicated.”

What was missing, in his view, was an adequate means to bring together these seemingly distinct sets of expertise. To that end, he appealed to the membership of the American Philosophical Society, suggesting that “as the oldest American scientific body, its activities spanned and were involved in the whole history which is here under consideration. In a word, there would seem to be no society which might more appropriately support such a program [emphasis added].”

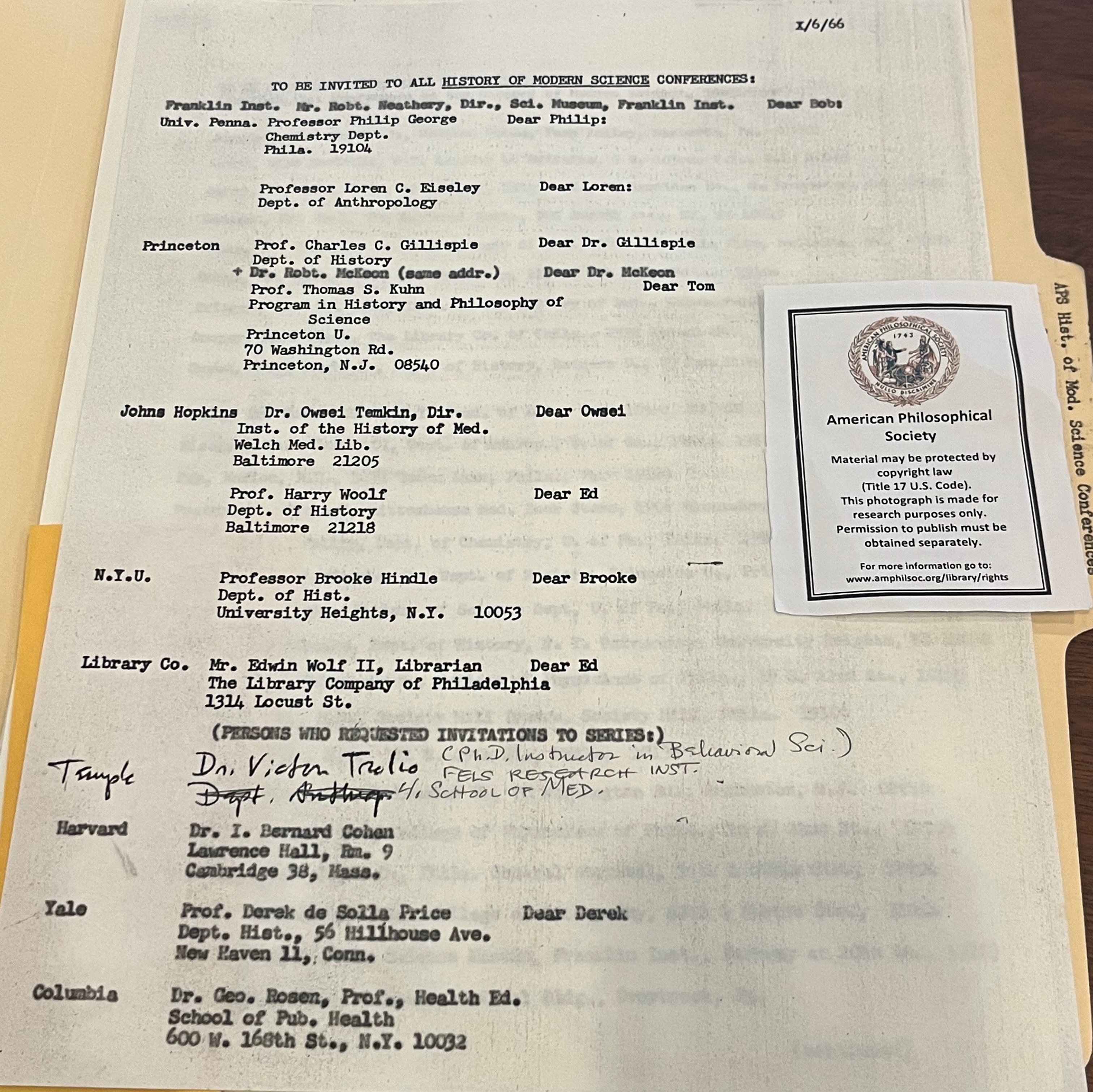

Shryock would have an opportunity to implement his ideas for an APS program for the history of science upon his appointment as the Society’s Librarian in 1959. This program drew upon the expertise of the APS’s scientist Members as well as a growing community of professional historians of science, and was organized around three interrelated components: 1) collection development, 2) academic programming and curriculum, and 3) public outreach. For example, between 1966 and 1967 the Library hosted a series of conferences that brought together experts in fields including medicine, physics, biology (especially genetics), technology, government science, and anthropology to discuss how the APS could strategically build its archives to provide resources to scholars working in those areas. This type of thinking also aided the 1961 creation of the joint Committee on the History of Theoretical Physics, which under the direction first of historian of science Thomas Kuhn (APS 1974) and, later, theoretical physicist John Archibald Wheeler (APS 1951), set out to collect primary source materials and oral histories preserving the history of quantum physics. Shryock later remarked that Kuhn’s publications from this initiative played “an important part of the Library’s public relations program.”

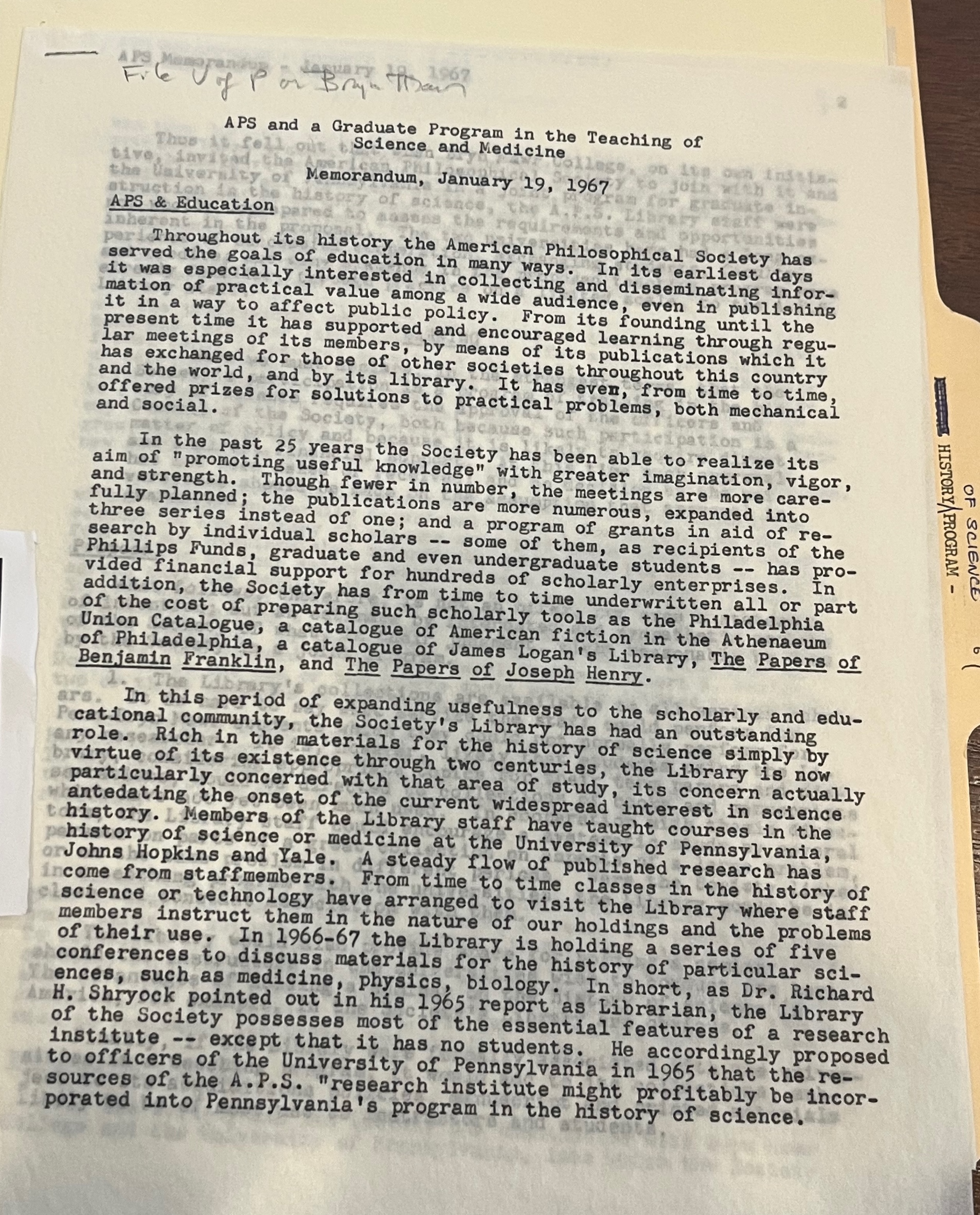

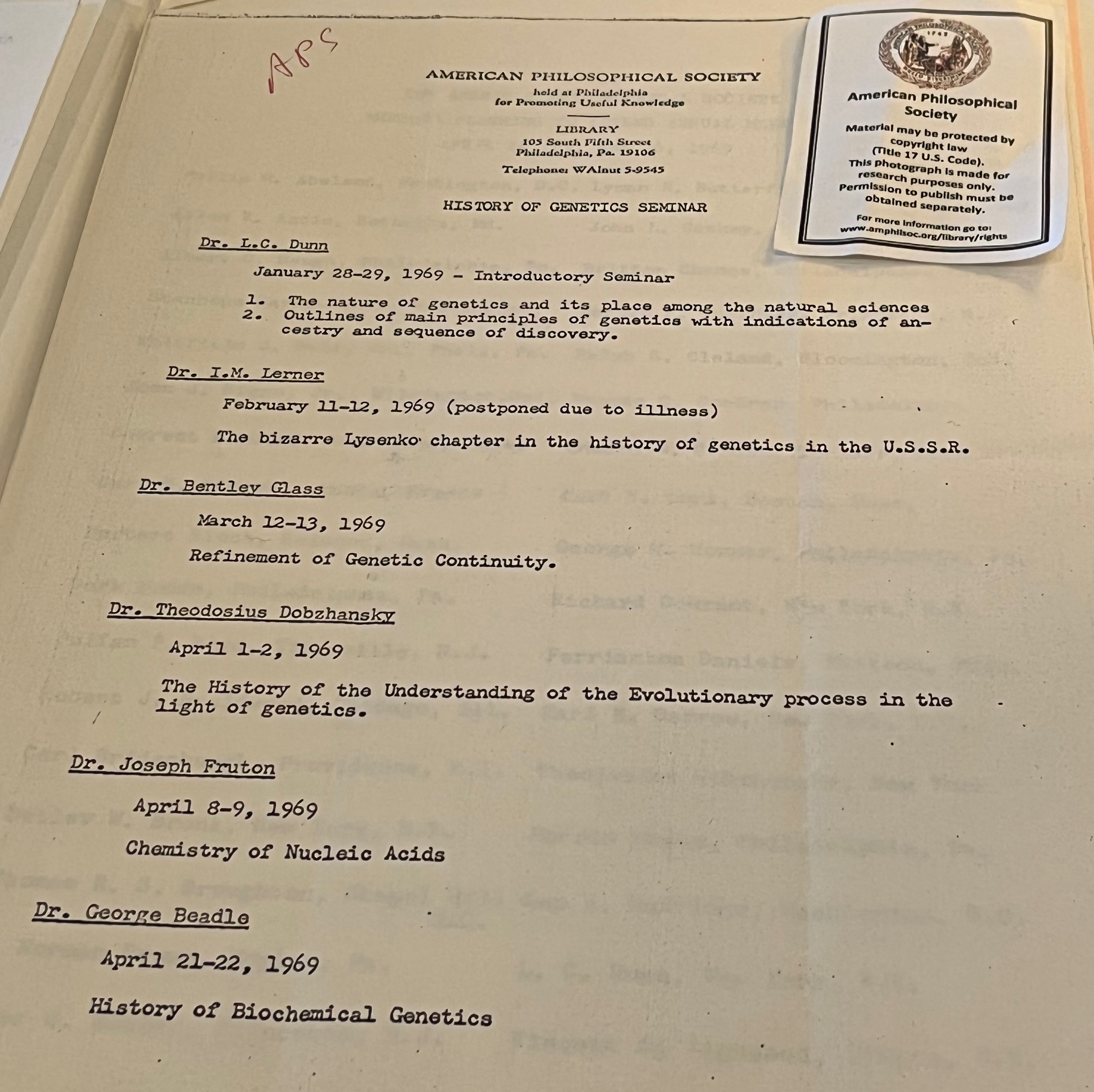

Yet of all the elements driving Shryock’s vision for the field, building a more cohesive relationship between the APS’s collections and the development of dedicated curricula in the history of science remained key. As he described in his 1965 Librarian’s report, while the APS’s Library had “most of the essential features of a research institute… it has no students.” This would change in 1967 when the APS received a $250,000 grant from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation to launch a five-year program in the history of science in collaboration with Bryn Mawr College and the University of Pennsylvania. This funding facilitated the hiring of several new faculty members to teach history of science courses–including historian of chemistry Arnold Thackray, who would become a key figure in the expansion of UPenn’s Department of History and Sociology of Science and the establishment of the Chemical Heritage Foundation (now the Science History Institute). But perhaps more critically, the program’s inclusion of targeted seminars on topics like the history of genetics created a way for leading scientists and APS Members like L.C. Dunn (APS 1943) and Theodosius Dobzhansky (APS 1942) to engage directly with the next generation of aspiring historians of science. This seminar series in turn generated content for a variety of APS publications–including the Mendel Newsletter, launched in 1968–and inspired other scientists to deposit their papers at the APS.

Although the program officially ended in 1974, fifty years later this work offers an important roadmap for the APS’s recently-launched Center for the History of Science. As head of the Center, I have found much inspiration in Shryock’s vision for the APS, and am committed to continuing to mobilize the Library’s history of science collections in ways that honor and bring together the expertise of both scientists and historians. While both the field of history of science and the APS have grown dramatically since the 1960s, Shryock’s words offer a clear direction for the mission of the APS’s Center for the History of Science in the 21st century:

“It would promote the use of the library in a systematic way…it would enrich the Library through purchases recommended by specialists in more fields than any acquisitions librarian is master of, and increase the number of scholarly papers offered to the Society for Publication, since some of the work done by instructors and students in the program would naturally be directed to the Transactions and Proceedings. Most important, it would involve the Society and some of its Members actively in an educational program for which they would be in part responsible in other than a financial way. It would, in short, add another dimension to the Society’s capacity for promoting useful knowledge.”

References

Whitfield J. Bell, Jr., “Richard H. Shryock: Life and Work of a Historian,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 29, no. 1 (1974): 15-31.

Bentley Glass, A Guide to the Genetics Collections of the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia: APS, 1988).