Benjamin Franklin’s Papers: Survivors of the American Revolution

This week marks the 315th birthday of Benjamin Franklin, who founded many institutions in Philadelphia, including the American Philosophical Society.

The APS’s Library & Museum holds about 75 percent of Ben Franklin’s papers, but the Society did not receive these items directly from Franklin. Prior to arriving at the Society, the papers went through quite an ordeal.

When Franklin left for France in 1776, he left his papers with his friend and fellow Pennsylvania Assembly member Joseph Galloway. Galloway kept the papers in his vault, a stone building on his property, along with some of his family’s papers and early Bucks County records.

By the time of the American Revolution, Galloway, a Loyalist, believed that the colonies should remain under British rule. On November 30, 1776, Galloway left Trevose and fled to New Brunswick, NJ behind British lines. At some point between the fall of 1776 and 1778, when Galloway fled to England, Trevose was raided. Some of the papers were stolen and others were left scattered about the grounds. Some accounts date this incident to the fall of 1776 and others to during the British occupation in 1777-1778, with some attributing it to "rebels," "a mob," "soldiers," and "a body of armed men," and others to the British army."

Franklin had foreseen this possibility. In 1777, he had asked his son-in-law, Richard Bache, about the papers held by Galloway:

“I wish to know some Particulars from you, viz. Whether when your Family went into the Country you remov’d the Houshold Goods, Plate, &c. and what became of the Chest of Papers I put into Mr. Galloway’s Hands as one [of] my Executors? It was directed to my Son, with the Key in a Letter of the same Direction to be delivered after my Decease. The Chest contain’d all my political Correspondence and some valuable Manuscripts.”

- Benjamin Franklin to Richard Bache, May 22, 1777 (Yale University Library)

Unfortunately no one had retrieved the papers for Franklin. A year later, Bache reported that the chest of papers had been broken open:

“Your chest of papers left with Mr. Galloway I am told was broke open at Trevoes and the papers scattered about. I shall go up thither today or tomorrow to look after them, if I can pick any of them up, shall take care of them.”

- Richard Bache to Benjamin Franklin, July 14, 1778 (American Philosophical Society)

Franklin’s daughter Sarah (“Sally”) Franklin Bache reported that some of the papers had been removed and that some were scattered about, but that they were safe as of October 1778:

“The Chest of papers you left with Mr. Galloway Mr. B. went up about. Bob brought them to town. The lid was broke open and some few taken off the top, Mr. B collected those about the flour [floor] had it naild up and they are all safe here. Mr. Galloway took not the least care of them, and used you as he did every body else very ill.”

- Sarah Franklin Bache to Benjamin Franklin, October 22, 1778 (American Philosophical Society)

Richard Bache later regretted his failure to act sooner and gathered what he could, but could not locate Franklin’s letterbooks with copies of his letters to others. Franklin urged Bache to ask others whether they might have seen or heard of the whereabouts of the letterbooks:

“Among my Papers in the Trunk which I unhappily left in the Care of Mr. Galloway, were eight or ten quire or 2 quire Books of rough Drafts of my Letters, containing all my Correspondence when in England, for near twenty Years. I shall be very sorry if they too are lost. Don't you think it possible, by going up into that Country, and enquiring a little among the Neighbours, you might possibly hear of and recover some of them…”

- Benjamin Franklin to Richard Bache, September 13, 1781. Bristol Rhode Island Historical Society; al (draft): Library of Congress

Three years later, Franklin was still inquiring about his letterbooks:

“On my leaving America I deposited with that Friend for you a Chest of Papers, among which was a Manuscript of 9 or 10 Volumes relating to Manufactures, Agriculture, Commerce, Finance, etc. which cost me in England about 70 Guineas; and Eight Quire Books containing the Rough Drafts of all my Letters while I liv’d in London. These are missing. I hope you have got them. If not, they are lost.”

- Benjamin Franklin to William Franklin, August 16, 1784 (British Museum), published in Smyth, Albert Henry, Writings of Franklin (1906), page 253

The letterbooks were, unfortunately, never found. For this reason, most of Franklin’s papers consist of letters to Franklin, rather than letters from Franklin. However, Bache was able to rescue a large amount of materials, which represent a good amount of the Franklin Papers that eventually found their way to APS.

In his will, Franklin left his papers to his grandson, William Temple Franklin, known as Temple. Intending to publish his grandfather’s papers, Temple set off for London with a portion of them, but left the largest portion with family friends, the Fox family, near Philadelphia. There they sat largely unused for forty years until American historian Jared Sparks used them for his published Works of Franklin, shortly after Temple finally published some of his grandfather’s papers.

In 1840, Charles Pemberton Fox and his sister Mary Fox gave the collection to the American Philosophical Society, where they have been ever since. They were cataloged in the 1840’s and again in 1900, when former APS Librarian I. Minis Hays compiled his multi-volume catalog of the Franklin Papers, with summaries of each document.

At that time they were also silked by manuscript restorer William Berwick of the Library of Congress. The silking process, no longer used, consisted of gluing documents on to stiff paper with a layer of fine silk to preserve them. Silked documents have a stiff, board-like feeling and appearance.

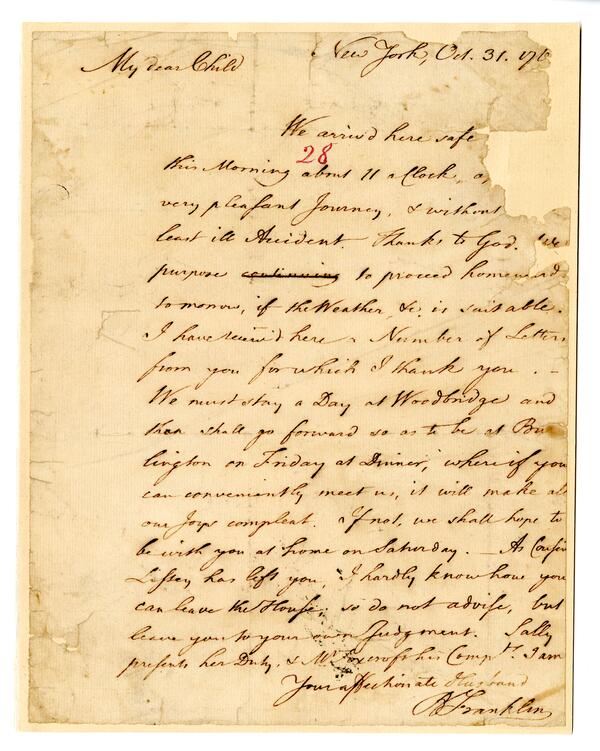

The document seen here bears some evidence of the rough treatment the papers received prior to their arrival at APS, such as tears and residual evidence of the mud in which Richard Bache found them.

A curious aspect of the APS Franklin Papers is that the collection includes letters and Pennsylvania documents dating back to 1642, although Franklin was not born until 1706. An examination of the finding aid for the early portion of the collection shows that 22 of these items seem to have some connection with the family of Grace Growden Galloway, Joseph Galloway’s wife.

The original owner of Growden Mansion was Grace’s paternal grandfather, Joseph Growden, a judge and close friend of William Penn, who also served as Attorney General. Joseph’s son Laurence, Grace’s father, was Chief Justice of Pennsylvania and Speaker of the Assembly. The Growden-Galloway vault building thus had held many early Bucks County and Pennsylvania papers.

It’s possible that Franklin just happened to have these early documents in his possession. However, their presence in the collection more likely stems from the provenance of Franklin’s papers—the history of the papers between Franklin and the APS. The APS cataloged these items at the time and they all became part of the Benjamin Franklin Papers. Given the history of the papers, however, it seems likely that these were intermingled with Franklin’s papers when Richard Bache salvaged them from the Galloway estate, where Bucks County records as well as Growden and Galloway papers were stored.

When Michael Miller, Assistant Head of Manuscripts Processing, re-cataloged the Franklin Papers several years ago, APS made the decision to retain them with the collection, as they already had been assigned “volume” and “folio” numbers and were cataloged as part of the collection by I. Minis Hays at the turn of the 20th century. However, the presence of these Growden and early Bucks County items in the collection most likely resulted from the incident during the Revolutionary War.

You can view the inventory of these items with short descriptions in the Benjamin Franklin Papers finding aid.

The Galloway home, Trevose, still exists in Bensalem Township, Pennsylvania. It is known as Growden Mansion, as it was the family home of Galloway’s wife, Grace Growden Galloway, daughter of Lawrence Growden. The stone building in which the papers were kept still stands on the property and the house bears bullet holes from the Revolutionary War. The property is owned by Bensalem Township and is open for tours by appointment.

The APS acquired its second largest accession of Franklin Papers from the Bache family in the 1930s, and continued to acquire Franklin material throughout the years, including what may be a portion of one of the missing letter books. APS now holds about three-quarters of Franklin’s known papers.

A somewhat smaller collection of Franklin Papers held by the Fox family was overlooked for another 25 years. During the Civil War, the family sold some old papers from their barn to a paper mill. A house guest, identified as Mrs. Holbrook, noticed that some of the papers bore Franklin’s handwriting. She rescued them and left the papers to her son, George O. Holbrook, who, with the encouragement of physician S. Weir Mitchell, sold the collection to the University of Pennsylvania in 1903.

As for the papers that William Temple Franklin took to London, they were discovered in the 19th century in a tailor shop below where Temple had lived, where they were being used as clothing patterns. They were rescued, and after a series of legal issues, eventually were donated to the Library of Congress.

Fortunately, most of Franklin’s papers have survived and are housed in several repositories for research. They also are published in the Papers of Benjamin Franklin (Yale University Press) and are available for research and full-text searching at The Papers of Benjamin Franklin website.

More details about the history of the Franklin Papers as described here can be found in Whitfield J. Bell Jr.’s Franklin’s Papers and The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania History, Volume XXII, No. 1 (January 1955).