"Uninterrupted Sleighing, and of the Very Best Kind"

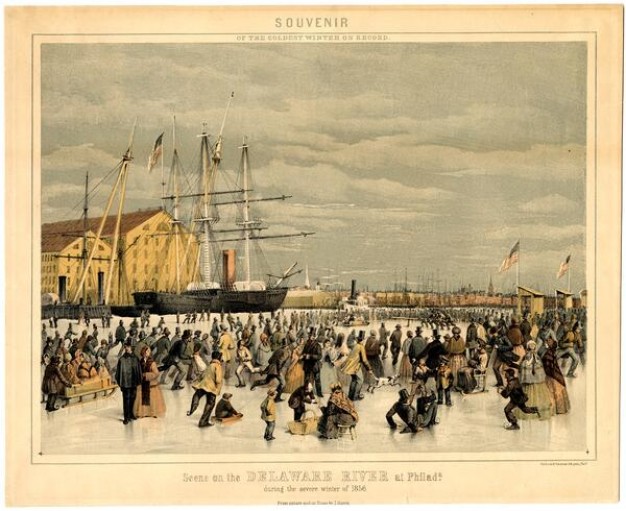

This winter’s weather has been remarkably mild in Philadelphia, so it may be the perfect time to share an artifact in our Print Collection showing a singularly different winter of years past. The color lithograph above, by Southwark-based artist James Queen, titled “Souvenir of the Coldest Winter on Record,” depicts a lively scene on the frozen-over Delaware “during the severe winter of 1856.” In this colorful landscape, revelers of all descriptions frolic on the ice in sleds, on ice-skates, and in shoes presumably studded for traction, while Philadelphia’s docks and buildings are visible in the background. In the center of the group, a team of men push a pole on an axis to create a sort of sled-carousel by centripetal force, which looks like a lot of fun! Another contemporary account relates another picturesque result of the constant ice—from the end of December 1855 “until near the middle of March, there was uninterrupted sleighing, and of the very best kind. Week after week, and, it may be said, month after month, we could hear almost the constant sound of sleigh-bells.”

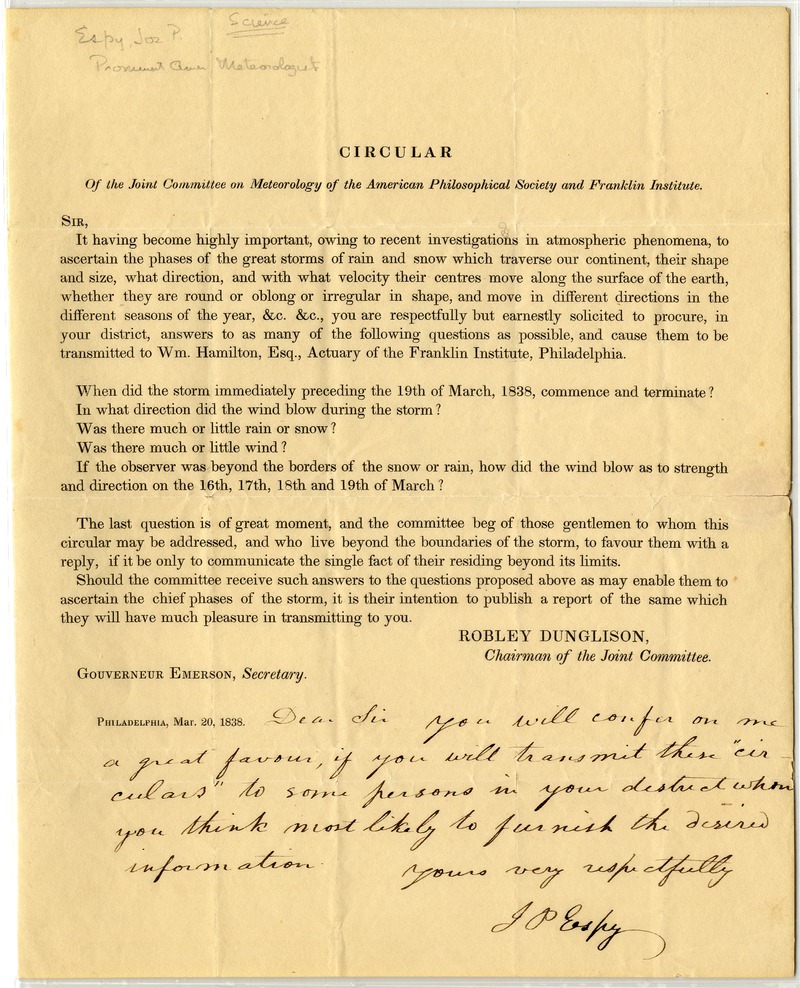

Clearly these winter scenes warranted souvenir status in general jollity. But exactly how cold did the weather need to be considered the “coldest on record”? This is a surprisingly difficult question to answer! The U.S. had no Weather Bureau at the time, and meteorological observation was carried out by volunteer weather recorders spread across the country, communicating their findings to major scientific institutions like the American Philosophical Society, the Franklin Institute, and the Smithsonian Institution by mail or telegraph. These results came from far-flung, relatively non-standardized instruments of different kinds and calibrations. And while they might not be as reliable as we in the present would like, they are the sources that we have to work with.

One major contributor of barometric readings in the city of Philadelphia was James A. Kirkpatrick, a teacher at Central High School and a graduate of its first class (1842). Three times each day, for twenty-five years, Kirkpatrick measured a variety of factors including temperature (wet and dry bulb thermometers), rainfall, barometric pressure, and wind conditions in the city. His observations were considered reliable and published regularly as datasets in The Journal of the Franklin Institute. Kirkpatrick’s readings confirm the chilly conditions indicated by the Delaware River ice-skating scene: he reports the mean daily temperature for the winter of 1855-56 at 29.3℉, a decrease of 2.3℉ from that of the winters over the previous five years (By contrast, National Weather Service data shows a mean daily temperature of 36.9℉ for the winter of 2018-19). The coldest day that winter, according to Kirkpatrick, was January 9th, 1856, when the mean was -1℉. Cold, indeed!

Collections related to historic meteorology at APS:

Meteorology Collection, 1748-1822 (Mss.551.5.M56)

[James Madison] Meteorological journals, 1784-1788, 1789-1793 (Mss.551.5.M26)

[Michael Jacobs] Meteorological observations made for the Franklin Institute, 1839-1865 (Mss.551.5.J12)

References:

“James A. Kirkpatrick,” The Phonographic Magazine 11 (October 15, 1897): 320-322. Retrieved from Google Books.

“Report of the Chester County Medical Society,” Transactions of the Medical Society of the State of Pennsylvania (1857): 131-160. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015076621310.

Kirkpatrick, Prof. James A. “Abstract of Meteorological Observations for February, 1856, and for the Winter Quarter ending February 29th, 1856, made at Philadelphia, Pa.,” Medical Examiner 236 (April 1, 1856): 256. Retrieved from ProQuest.