Sophonisba Angusciola Peale Sellers, scientist and artist

Sophonisba Angusciola Peale was born on April 24, 1786, to noted American polymath Charles Willson Peale and his wife Rachel Brewer Peale. The second daughter of the couple’s six surviving children, Sophonisba (nicknamed Sopy) was named after Renaissance portrait painter Sophonisba Angusciola. Most of the Peale children were named after artists and intellectuals whom Charles admired, and Sophonisba shared her father’s diverse interests in both art and science. During her childhood at the Peale’s family home—now the American Philosophical Society’s Philosophical Hall— she lived among the Peale Museum and its growing natural history collection.

Charles Willson Peale’s interest in natural history developed into his own acquisition and taxidermy of native bird specimens, and his children were involved in his museum and intellectual pursuits as well. By the time she was 17, Sophonisba accompanied her father on ornithology trips with her own Fuzee, or flintlock shotgun. By going with her father on these trips and conducting her own taxidermy on specimens she collected, she is considered the first female ornithologist in American history. Her younger half-brother, Titian Ramsay Peale, followed in her footsteps and became a noted ornithologist himself.

While she and her father remained in Philadelphia during the 1803 yellow fever epidemic, Sophonisba used her extensive education to create labels in Latin, English, and French for 140 museum display cases and the 760 specimens within. Charles considered this task invaluable to the museum, especially as the Peale Museum was the first to use Linnaean taxonomy to arrange and label specimens. Charles wrote in an October 1804 letter to inventor John Issac Hawkins that “Rubens & Sophonisba are somewhat advanced in Latin” and had discontinued their Latin lessons by November of that same year to focus on French. In a June 1805 letter to Rubens (then staying in Cape May), Charles mentions Sophinsba’s skill at painting still lifes of fruit.

Charles wrote to his other daughter Angelica Peale Robinson in 1804 that 18 year old Sophonisba was unable to travel from Philadelphia for her debut in society, though Charles subscribed to the best of the city’s assemblies that season for her benefit, as Sophonisba had “accomplishments” and would “shortly be admired for her Vocal powers, as she improves daily.” During Charles’s travels, his joint letters to Sophonisba and Rubens treated them as heads of the household as they guided their younger siblings to help manage the museum.

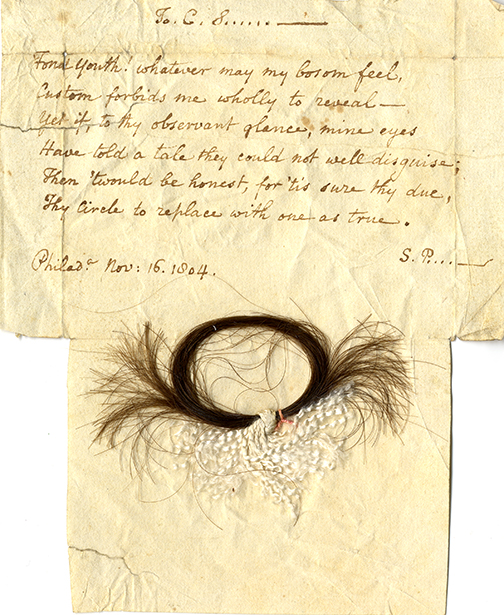

The next year, engineer Coleman Sellers began courting Sophonisba. Sellers was himself a descendent of one of the first land grant holders in Pennsylvania. During their courtship, the couple exchanged locks of their hair. To accompany her lock, Sophonisba wrote: “To C. S….: Fond youth! Whatever may my bosom feel, custom forbids me wholly to reveal—Yet if, to thy observant glance, mine eyes Have told a tale they could not well disguise; then ‘twould be honest, for ‘tis sure thy due, Thy circle to replace with one as true.”

The couple married in 1805 and stayed that winter with her father and his third wife Hannah Moore before moving to the Sellers family estate in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania. Coleman Sellers helped fund his brother-in-law Rembrandt’s trips to Europe for the dual purposes of education and networking. Sophonisba gave birth to four sons and two daughters; two of her sons became noted engineers and inventors, and the youngest, Coleman Sellers II, was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1872. Her daughter Anna became a landscape painter who studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Coleman Sellers died in 1834; Sophonisba never remarried. After Coleman’s death, Sophonisba remained in Upper Darby, taking over her daughter Elizabeth’s household in 1840 during her daughter and son-in-law Alfred’s absence in England. After Elizabeth’s 1841 death, Sophonisba helped raise her two grandchildren, Charlotte and Fanny Harrold, according to an account book she kept for detailing household expenses.

There is little evidence that Sophonisba continued (or was even allowed to continue) her formal scientific or artistic studies after her marriage, unlike her famous brothers. There are indications that she did continue to produce sketches and other artwork, though none have yet been located or identified. The Society retains some of her family correspondence within the Peale-Sellers Family Collection. Like many women of her era, she quilted. One quilt in a variation of the Star of Bethlehem pattern from 1850 survives at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Sophonisba died on October 26, 1859, and was buried in New Darby’s Upper Jerusalem Burial Ground. Her remains were later moved with the rest of the Sellers family plot to West Laurel Hill Cemetery. Interestingly, out of all her living children, both her son Coleman Sellers II and her daughter Anne Sellers were named executors of the will. Anne received all home goods, including pictures, not otherwise bequeathed elsewhere, and Coleman received “my bookcase and the new church books and my scientific works therein.” While Sophonisba did not leave behind the same public legacy as her brothers, her will offers clues of a woman who continued to participate in scientific discourse even after her marriage.