Society Observes Juneteenth 2020

Juneteenth marks the date that word of the Emancipation Proclamation made its way to Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865 and Union troops informed enslaved people that they had been declared free over two years earlier. On June 16, 2020, the city of Philadelphia declared Juneteenth an official city holiday to recognize the end of slavery in the United States. The American Philosophical Society joins the city of Philadelphia in observing this holiday and will be closed for business so that staff can take time to reflect on the history and persistence of racism in the United States so that we may individually and collectively affect change within ourselves and our nation.

The issue of slavery followed the Society’s founder Benjamin Franklin over his lifetime as he first profited from the system, then advocated for its abolition. He enslaved several people between 1735 and 1781 and published advertisements for the sale of slaves in his Pennsylvania Gazette. As a prominent scientific mind, he also played a complicit role in the underpinnings of scientific racism. Late in his life, Franklin had embraced the abolitionist movement and joined the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, going on to become their president in 1787 and serving until his death. Franklin changed his views on race and equality through learning, listening, and conversations with those who advocated for freedom. We hope this time to reflect on our nation’s failings and opportunities to create a more perfect union will promote the same growth within our Society.

For this year’s celebration of Black freedom, APS Staff and Fellows have identified select collections and resources highlighting moments of Black self-determination over time. We hope you will explore these items, reflect on the long legacy of unfreedom in the Americas, and commit to the necessary work to create a better future. We are also spotlighting some of the great events that our peer institutions are hosting this year online.

Siding with the British paradoxically offered more opportunity for freedom for enslaved people during the American Revolution than fighting on the patriot side. Nearly 3000 Black men, women, and children were evacuated from New York City over the summer and fall of 1783 to Nova Scotia, London, and other places in the British Empire for new lives as free citizens. Interns from the CV Starr Center at Washington College are spending the summer researching Black and white Loyalists from Maryland using the rich collections of the Loyalist Claims Commission and the Carleton papers, available on microfilm in the new David Center for the American Revolution.

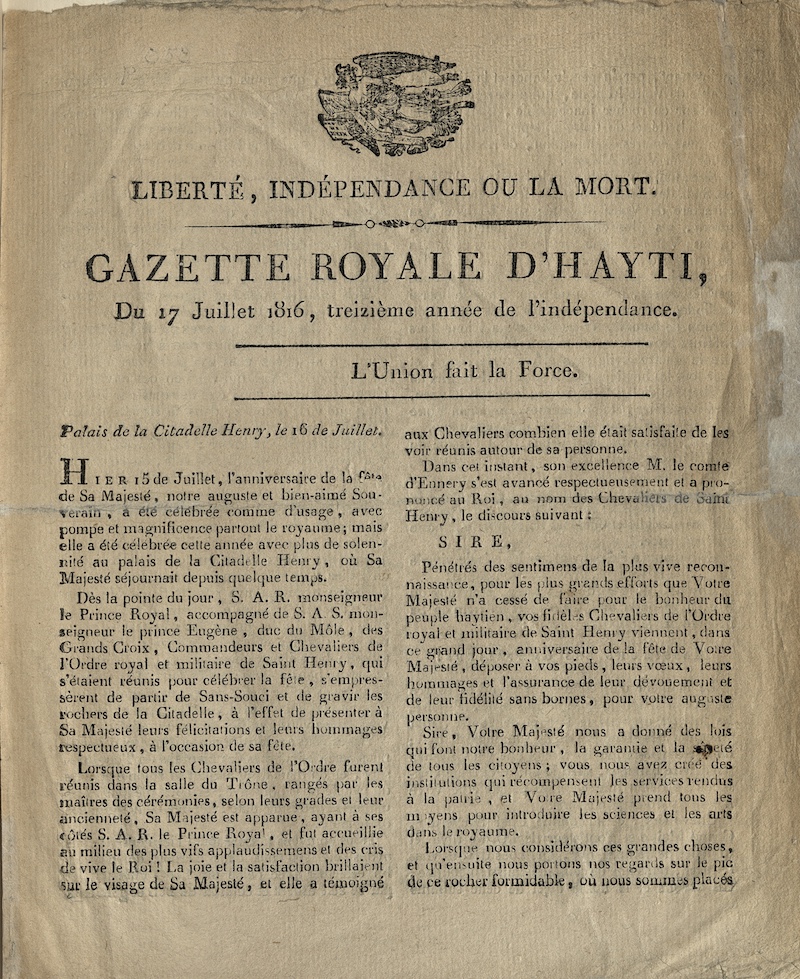

Fifteen years after the Declaration of Independence, the enslaved people of Haiti began a series of revolts that secured the first Black republic in the Atlantic World. Haiti’s leaders—Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, General Henry Christophe, and others—availed themselves of the printing press to do the necessary work of nation building. The APS holds a very rare collection of early Haitian newspapers, which can be read in the Digital Library. They have also been transcribed and put into context on the site La Gazette Royale d’Hayti.

In the early 19th century, Black Philadelphians fought for freedom in any way they could. The desire for freedom to worship God unencumbered by white prejudice drove Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and others to found the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1794 as an independent Black denomination. Mother Bethel Church (seen in the image here) began as a repurposed blacksmith’s shop that was moved to a few blocks away from the APS. The Hare-Willing Papers and the Kane Papers at the APS hold important financial and administrative records for early Black Philadelphia churches.

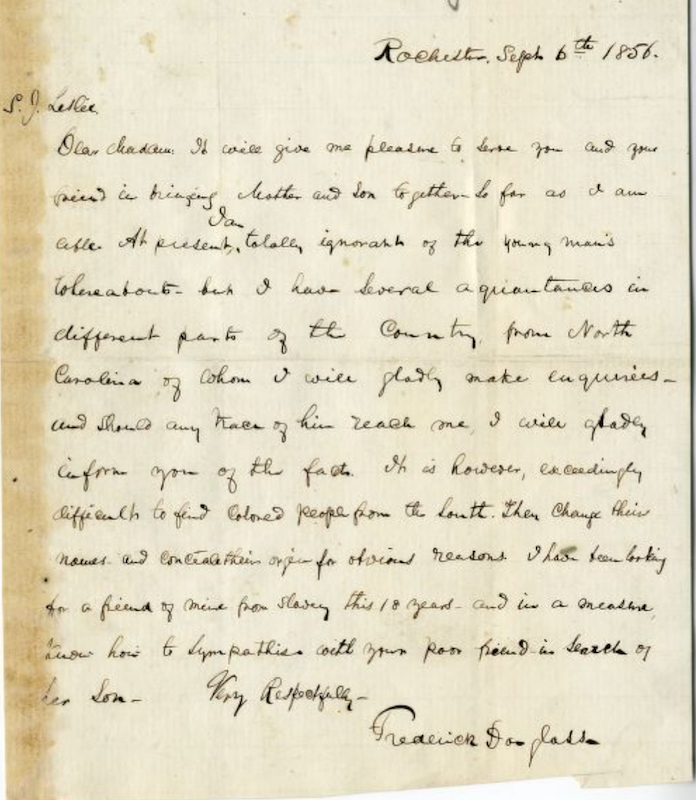

“It is exceedingly difficult to find Colored people from the South,” Frederick Douglass wrote in 1856 to an abolitionist helping a formerly enslaved mother find her son. “They change their names and conceal their origins for obvious reasons. I have been looking for a friend of mine from slavery this 18 years …” Douglass’ reflections remind us of the lengths to which people went in order to free themselves from slavery and the overwhelming desire to reconnect with family once free. In the same collection are letters from Mary Walker, the woman trying to find her son. Walker escaped from slavery when her owner brought her to Philadelphia from North Carolina in 1848. The decision to free herself, however, entailed leaving her mother and three children in bondage. You can read letters by Walker in the Lesley Collection. Read more about Walker’s life and efforts to reunite her family here.

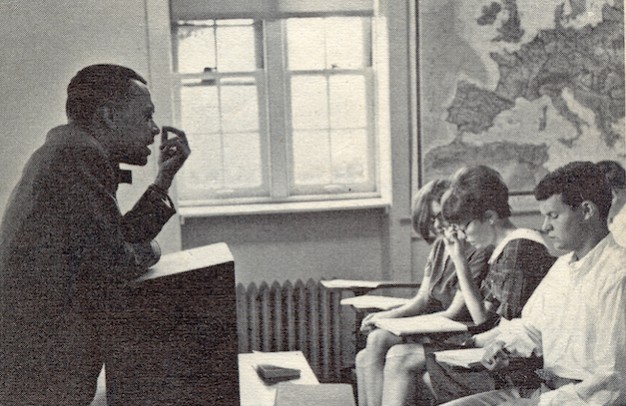

While the APS is known for its Early American collections, it also stewards important 20th and 21st century collections. A recent blog post highlights the career of William Shedrick Willis, a leading Black anthropologist of the 20th century, whose scholarship called for an overhaul of the discipline to advance the goals of social justice and civil rights, especially through cultivating new generations of anthropologists of color. The life of Willis is a powerful reminder that despite the passing of the 14th Amendment, Black claims to full equality in America have remained an ongoing struggle.

APS resources go beyond manuscripts and objects. While celebrating Juneteenth, it’s worth watching these two videos from previous APS lectures. The first is from Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw on Portraiture and the Development of African American Identity in the 19th Century in which she discussed how any piece of art can represent the layers of the creators behind them through the example of Moses Williams’ life and limitations as a slave of the Peale family. The second, from Thomas C. Holt, is Legacies “Dis-remembered:” Re-reading Moments of Emancipation, in which he re-tells moments of Emancipation during the Civil War, preceding and after the Emancipation Proclamation.

Please explore what some of our partners and peer institutions are doing to commemorate the day. Our friends at the Museum of American Revolution have a full day of programming planned and our friends over at the African American Museum in Philadelphia are co-presenting the 2020 Juneteenth Virtual Festival.