Revolutionary PHL: Exiled from Philadelphia: Quakers during the Revolution

In three recently digitized collections for the Revolutionary City portal, the James Hutchinson Papers (held at the American Philosophical Society), the Sarah Logan Fisher Diaries (held at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania), and the Wharton and Willing Family Papers (also held at HSP), users can now read accounts from a network of Philadelphia Quakers about their struggles during the revolutionary era.

Following the Society of Friends’ guidelines for pacifism, most Quakers refused to take up arms during the war. Some even saw taxation or using continental currency as means of involvement in the conflict. Because of this, Quakers were often regarded as being against the new government or aiding the British. In September 1777, 20 Quaker men were imprisoned for refusing to sign oaths of loyalty to the revolutionary government. They were transported from Philadelphia to Virginia to be exiled without an indication of how long they would be detained.

The James Hutchinson papers give insight into a family largely affected by the exile, as Hutchinson wrote letters to his exiled uncle Israel Pemberton keeping him informed of family and war matters. Frequently mentioned in the letters is Mary “Polly” Pleasants, who was at home with at least five young children while her husband, Samuel, her father, Israel, and several uncles were exiled. This collection also includes a letter from Rachel Pemberton to her husband, Israel, about the difficulties getting supplies for the winter and using several types of currency.

One of the most personal accounts of the Revolution comes from the diaries of Sarah Logan Fisher, two volumes of which were written while her husband, Thomas, was in exile. Roughly seven months pregnant and with a toddler, Fisher recounts her longing and despair during the separation. Just days after the exiles were relocated to Virginia, neighbors knocked on her door in the middle of the night, alarming everyone that the British were on their way to occupy Philadelphia. While many fled, she stayed even through several instances of her “being waked very early this morning by a very heavy firing which shook the windows.” After eight months of uncertainty and six months after the birth of his first daughter, Hannah, Thomas Fisher and the other exiles were released. In the years following Thomas’s return, Fisher writes of the triggering anxieties that resurfaced when her husband was away from her for long periods of time.

In the Wharton and Willing Family Papers, there are 12 letters from Thomas Wharton to his wife recounting the health of his fellow prisoners and their attempts to appeal to the government for release. Also in this collection are letters written to government officials while Wharton is in exile, including one to his cousin, Thomas Wharton, Jr., then serving as President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. While imprisoned, he makes his case to his influential cousin. An example of a family on two sides of the war, Wharton starts the letter with, “there would have been a time when thou would have esteemed it agreeable to receive a letter from me and notwithstanding our present situations are extremely different.”

The full scope of this story doesn’t stop with these three collections. In the diaries of two of the exiled men, James Pemberton and Thomas Fisher, we can explore detailed accounts of the exiles’ daily lives. In Elizabeth Sandwith Drinker’s diaries, we can dive into what it was like in Philadelphia for the network of Quaker wives who were left to face the British occupation and quartering soldiers in their homes, all while petitioning Congress and traveling to Washington’s headquarters to persuade the release of their loved ones.

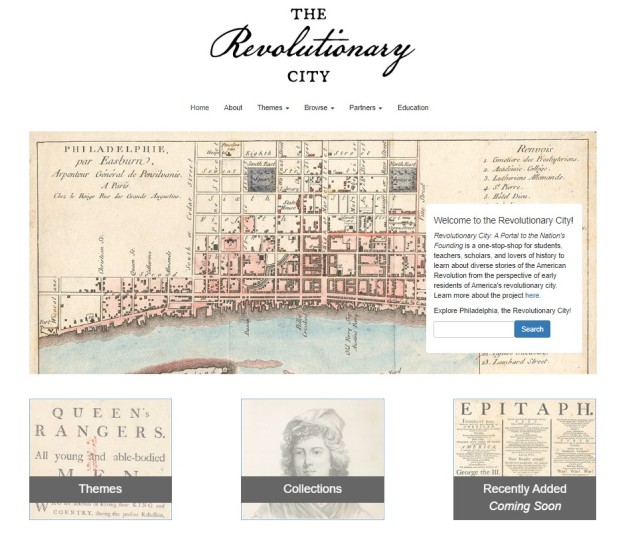

The letters and diaries of these families, now easily readable on the Revolutionary City website, help us understand the war’s impact on both these social networks and the Philadelphia Quaker community as a whole. By bringing together collections from these separate institutions for the first time digitally, portal users can see a more complete version of the Revolutionary War period easier than ever. See these documents and more on therevolutionarycity.org.