Revisiting the Expedition of Lewis and Clark

By Madeleine Engle, Cultural Fieldwork Initiative Intern, 2021

Over the past few months, I’ve had the pleasure of working in the Education Programs Department at the American Philosophical Society’s Library & Museum. While I had no idea what I was getting myself into when I arrived on my first day, I’ve since met many lovely people who have introduced me to what they’re passionate about. I’ve learned about 18th-century balloon disasters, and that Benjamin Franklin (great as he was) could never master his family’s soap recipe. I’ve learned that certain historical artifacts are so light-sensitive they need to be displayed under a black shroud so they aren’t damaged simply from sitting in the light. I also learned that museum work is a lot more exciting than I originally thought it could be.

During Fall 2021, I worked on a lesson plan about the Lewis and Clark expedition, which took place over two years and across 8,000 miles of the North American continent. It’s something many of us were taught about in elementary school: we hear about their bravery, forging a path through “unexplored wilderness,” and the help they received from Sacagawea. Then, Lewis and Clark are rarely mentioned again.

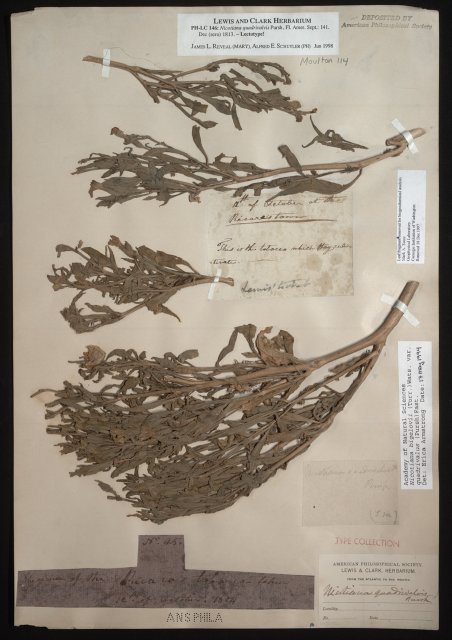

I believe that students can learn just as much from Lewis and Clark in 10th grade as they can in 2nd grade. However, as students get older, the questions they ask about these explorers must get more challenging. The Lewis and Clark expedition can influence how we understand the world around us from a scientific and a social perspective, informing Americans about the flora and fauna of the physical land we call home as well as the cultures and histories of groups that were here long before us (and still are).

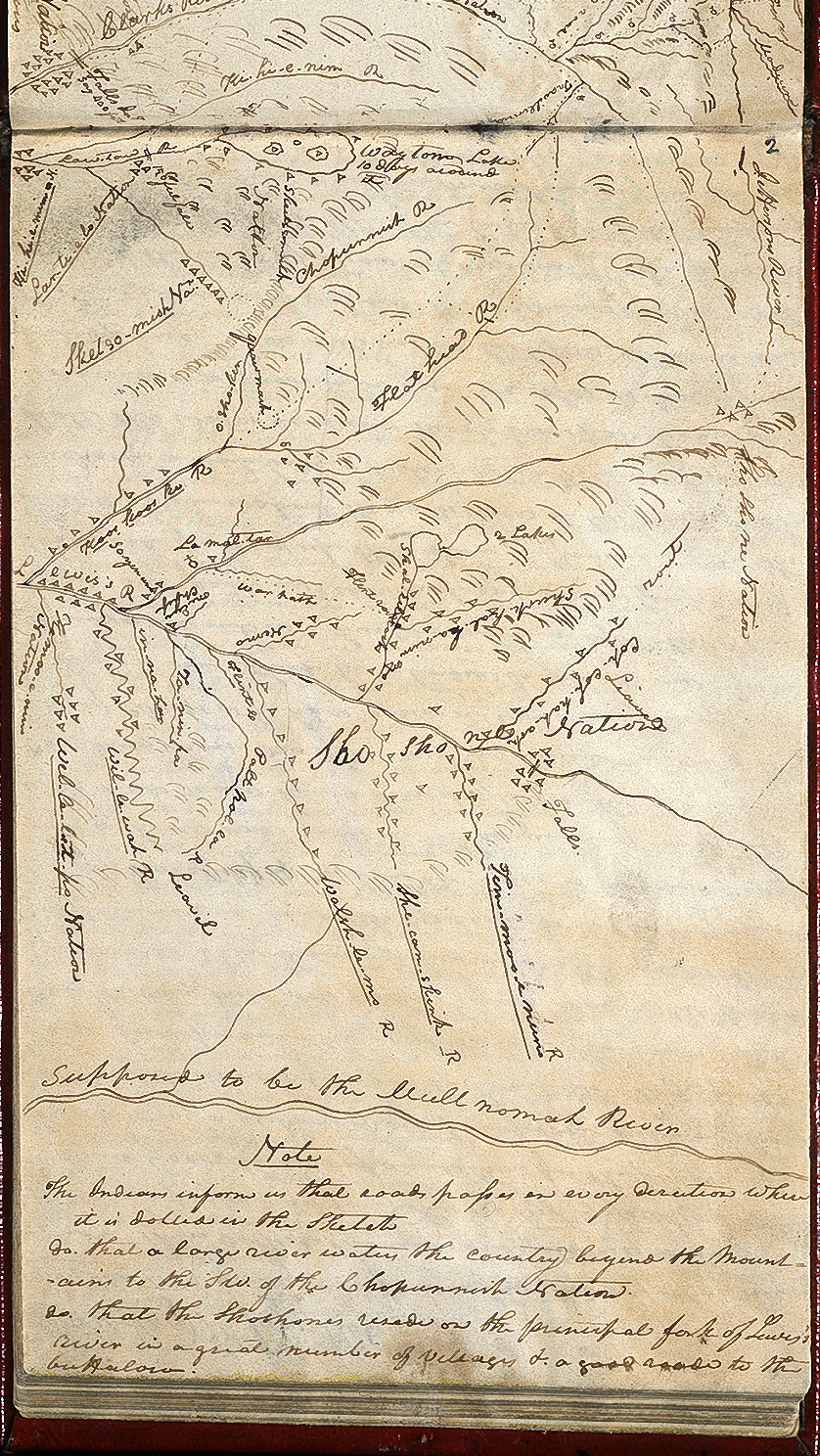

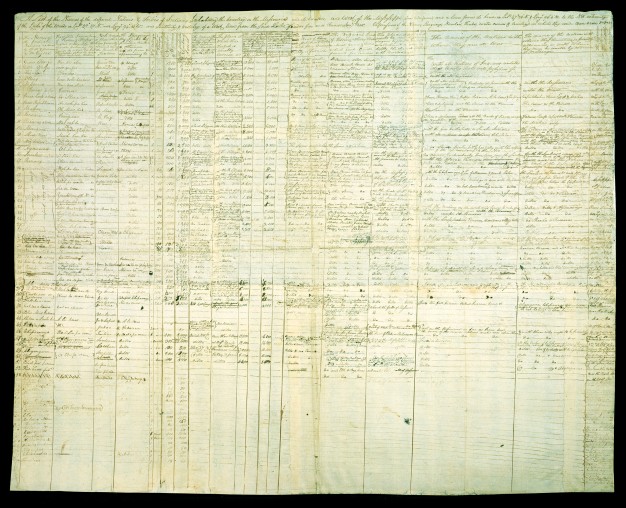

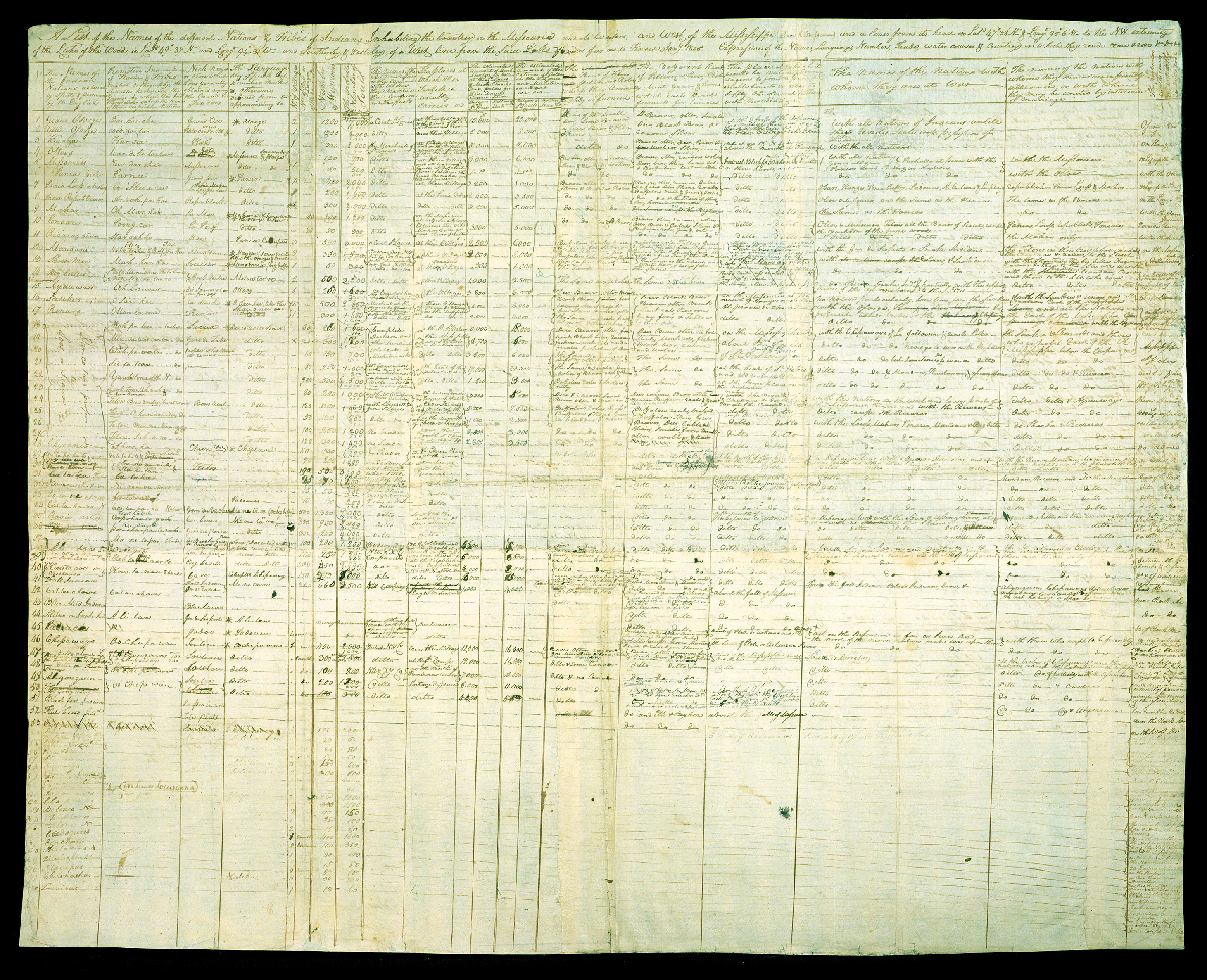

Lewis and Clark’s journals include hundreds of sketches of plants and wildlife, many of which had never been seen by Euro-American scientists before. This greatly expanded scientific knowledge of the United States and introduced scientists to the variety of species present in the territory acquired via the Louisiana Purchase. However, their journals also included information about the people they encountered. Lewis and Clark kept note of the Native American leaders they met, the kindness or hostility they experienced, and even the gifts they gave to Indigenous communities.

These two elements (the physical land and the social systems it was home to) were brought together in the maps they sketched of their travels. These primary sources show the complexities of Westward expansion. While Lewis and Clark were exploring territory that was, to American settlers, completely new, they were interacting with people who had lived there for centuries; the descendants of whom still live in those regions today. The expedition’s advances into the American West aligned with Manifest Destiny and set the tone for future relations between Native Americans and the United States. It’s sources like these that provide a more complete picture of the Lewis and Clark expedition, a picture that most of us might not have encountered in elementary school.