Papers of Amelia Susman Schultz, Franz Boas' last surviving student

In 2015—her hundredth year—Amelia Susman Schultz donated a portion of her papers to the American Philosophical Society, a small but important and unusual collection. They joined other materials of hers that had been brought to the Library 70 years earlier (and created up to 80 years earlier) as part of the American Council of Learned Societies Committee on Native American Languages (ACLS) Collection, comprising the research of Franz Boas and his colleagues at the end of Boas' life. Since its arrival, the ACLS collection has been central to the development of our Indigenous American strengths at the Library, and it is likely that no other contributors to the collection still survive.

The Amelia Susman Schultz Papers do much to fill in the gaps of her work as an anthropologist and linguist and later as a genetic researcher. The Papers are divided into three sections: fieldwork in the mid to late 1930s at Round Valley Indian Reservation, California; fieldwork at the end of the 1940s on the Brienzerdeutsch variety of German in Brienz, Switzerland; and much later work in the 1970s on Huntington's disease in Washington State. Susman's papers in the ACLS collection are mostly on Ho-Chunk, from her second dissertation at the end of the 1930s, in addition to a wordlist of Catawba and some notes and correspondence on Sm'álgyax/Tsimshian.

In the spring of 2018, after the release of our Indigenous Subject Guide for which I was brought to the Center for Native American and Indigenous Research to help finish, I sat down with Curator of Native American Materials Brian Carpenter to discuss the unprocessed collections that might be a priority. Brian mentioned Susman's more recently received papers, and their prominence and context, and I am quite sure I started processing them the same day, very eagerly, finishing them by the end of the month.

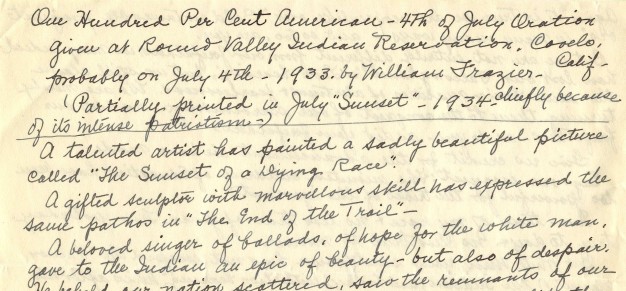

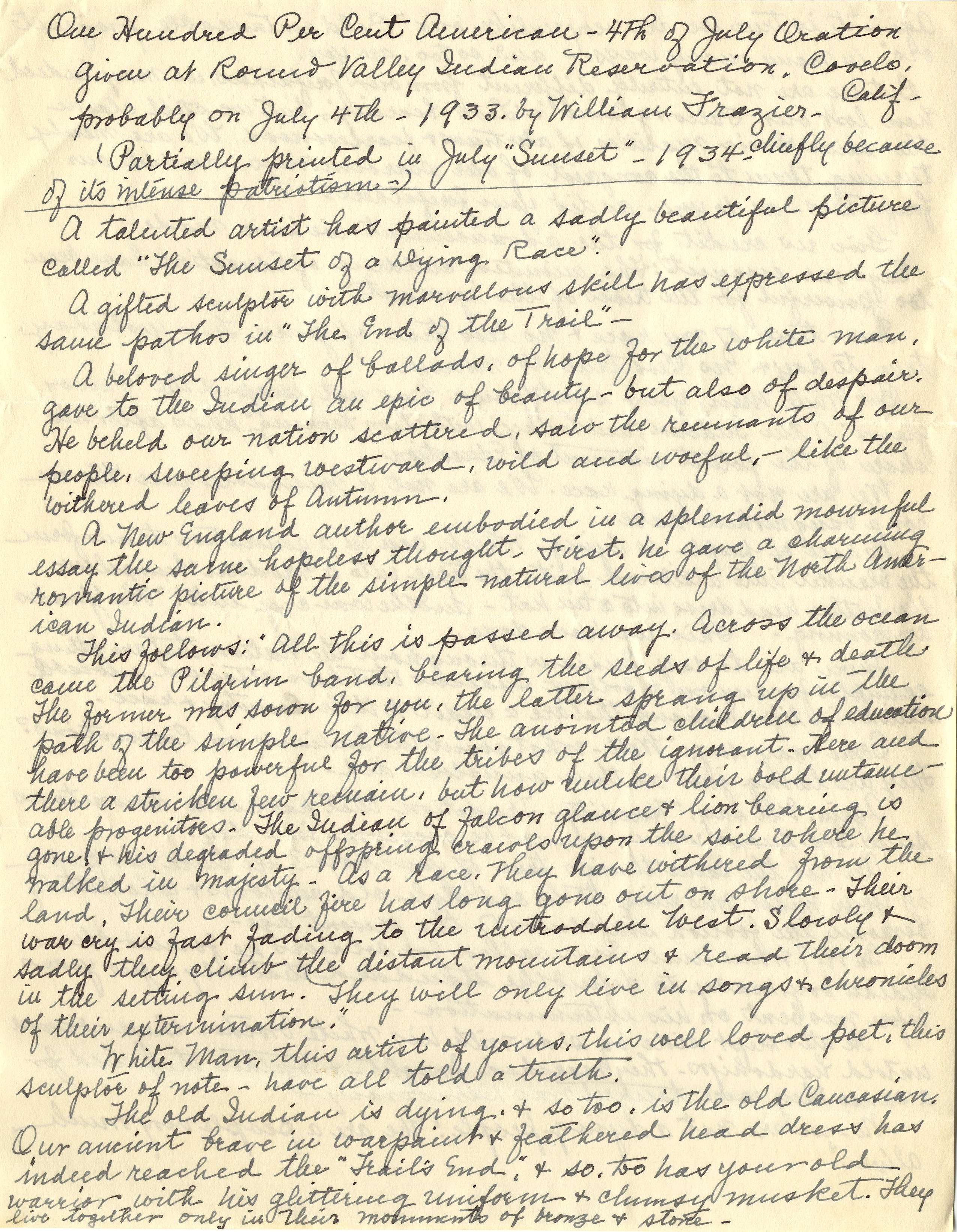

Susman’s work with residents of the Round Valley Reservation of California (Series II of the finding aid) involved a great many conversations about the social and economic life of the community at Covelo. Only a few generations after the creation of the reservation on Yuki land in the 1850s, in which settlers massacred Yuki people and forced removal of other peoples to the reservation, it is a unique portrait of the time, framed as a study of their “acculturation” to white culture—a dominant theme in anthropology in this era. Working under the direction of Ralph Linton—a colleague but ideological rival to Franz Boas at Columbia University—Susman expected to publish the resultant dissertation as part of Linton's edited volume "Acculturation in Eight American Indian Tribes," publication being at the time a requisite for completion of a Ph.D. Susman was asked by Linton, through Ruth Benedict (also a rival of Linton's), to withdraw her contribution to the book, citing potential for libel. Accounts differ as to the exact cause of the controversy: Susman posited around the time that it was to do with the mention of representatives in court cases involving Native Californian groups, while M. A. Baumhoff (1977:330) thought it more likely to be the "straight medicine" that was Susman's frank description of the genocidal treatment experienced by those at Round Valley at the hands of white colonizers.

Whatever the cause, Susman's book chapter would not appear until 1976. Having her publication rejected meant she was still without a doctorate, and so had to start from scratch on a second one. This is what brought Boas out of retirement to assist her on the production of a Ho-Chunk (formerly called Winnebago) grammar with Sam Blowsnake (Crashing Thunder) and his family as the main contributors. Eleven notebooks and two papers from this period between 1938 and 1939 are in the ACLS collection.

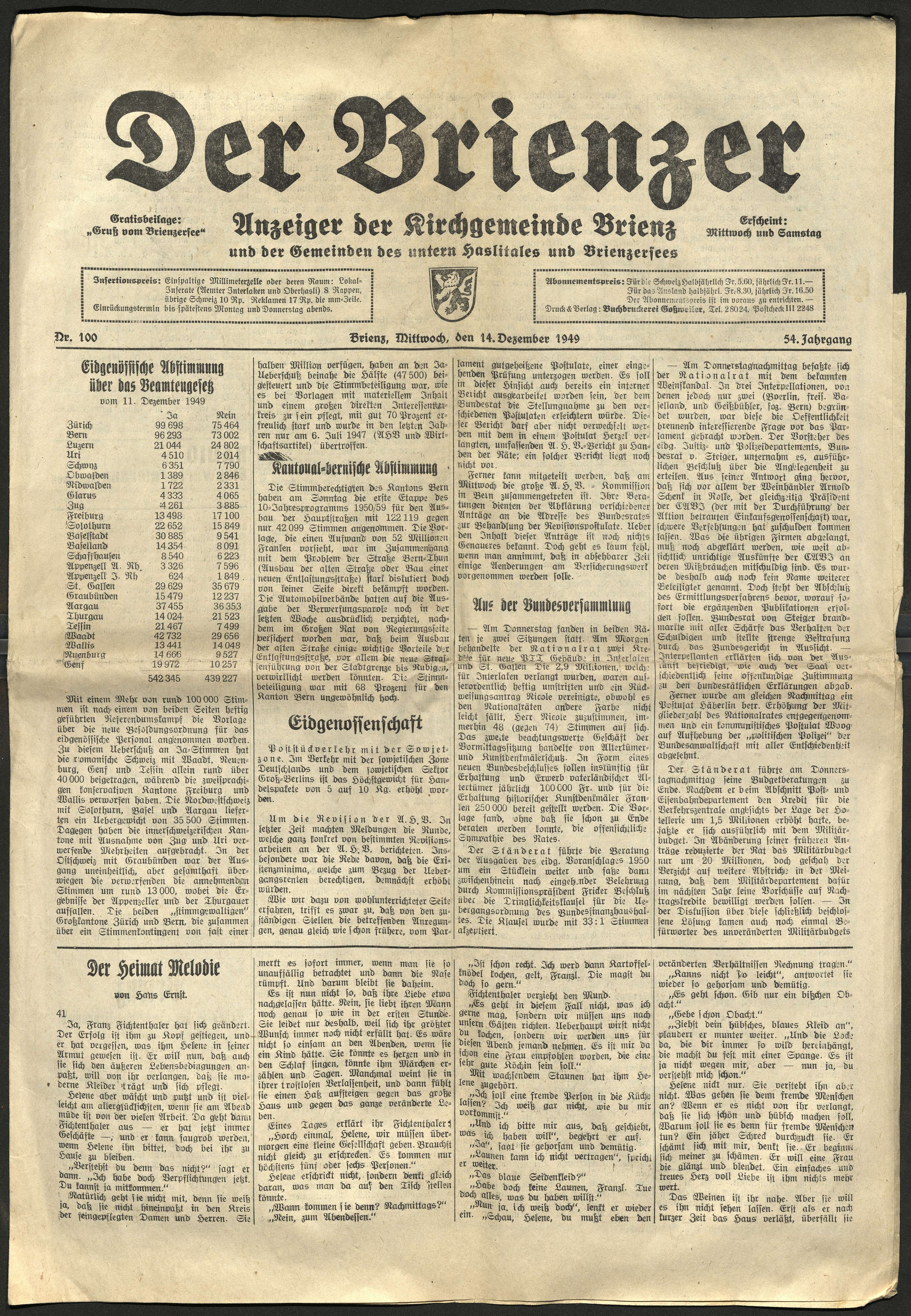

Susman later spent time in the village of Brienz, Switzerland, documenting the local social life and economy in field notebooks, slips, local printed materials, and a reel-to-reel tape (Series I in the finding aid). She wrote on Brienzerdeutsch (the local variety of German) as well as social organization and economy, including a paper on distinctive insults. For the majority of the remainder of her career, Amelia Susman Schultz left linguistics and anthropology, heading into social work and genetic research (a snapshot of which is in Series III). She has returned occasionally to remark on her increasingly unique position as someone who shared time with Boas, however. In 1977, while working at University Hospital at the University of Washington, she published a brief note in the International Journal of American Linguistics (IJAL) addressing claims about Boas' transcription preferences, and how much he mandated that his students follow his example, by quoting from correspondence he had sent to her. Much later in 2011, she gave a talk to the Society for Applied Anthropology titled "A Tribute to Boas", with chair Jay Miller.

Miller, a fellow anthropologist, deserves praise for helping to bring unpublished or difficult-to-find materials produced by Susman to light. In 2018 he self-published her full dissertation along with a biography and other related materials as "Acculturating Amelia"; he was also instrumental in ensuring that more of Susman's materials reached the American Philosophical Society, and we worked with him and the History of Anthropology Newsletter to digitize and publicize Susman's 1940 syllabary for the Ho-Chunk language. Having so many of her materials together at the American Philosophical Society Library is important not only for their long-time preservation and the opportunity to reconnect them with the communities with whom she worked, but for the broader picture they provide of her life and the pivotal moment in North American anthropology in which she participated.