For Now and For Later: (Re)Contextualizing Elsie Clews Parsons from a Pueblo Perspective

Before I began my internship, I knew I wanted to conduct research about Elsie Clews Parsons, a notorious anthropologist who conducted research in my Pueblo. She used extractive, and anti-Indigenous anthropological practices to research Isleta’s culture. Based on prior conversations I have had with Isleta Pueblo’s Tribal Archivist, Parsons collaborated with, and paid, a tribal member to produce a series of paintings depicting culturally sensitive traditions.

In a series of letters exchanged between Parsons and the tribal member, Parsons promised that these paintings would never be published or shared with others. However, after Parsons’ death, her student Esther Goldfrank decided to publish and share these paintings. These paintings have since been scattered throughout museums and archives across the U.S. with some of these paintings located here, at the American Philosophical Society.

Parsons’s relationship with the tribal member revealed to me the ways in which 20th-century anthropologists exploited Indigenous informants. In this case, Parsons paid a tribal member to create culturally sensitive paintings which are at the American Philosophical Society. Given that the tribal member willingly accepted money from Parsons, I found their relationship to be especially interesting.

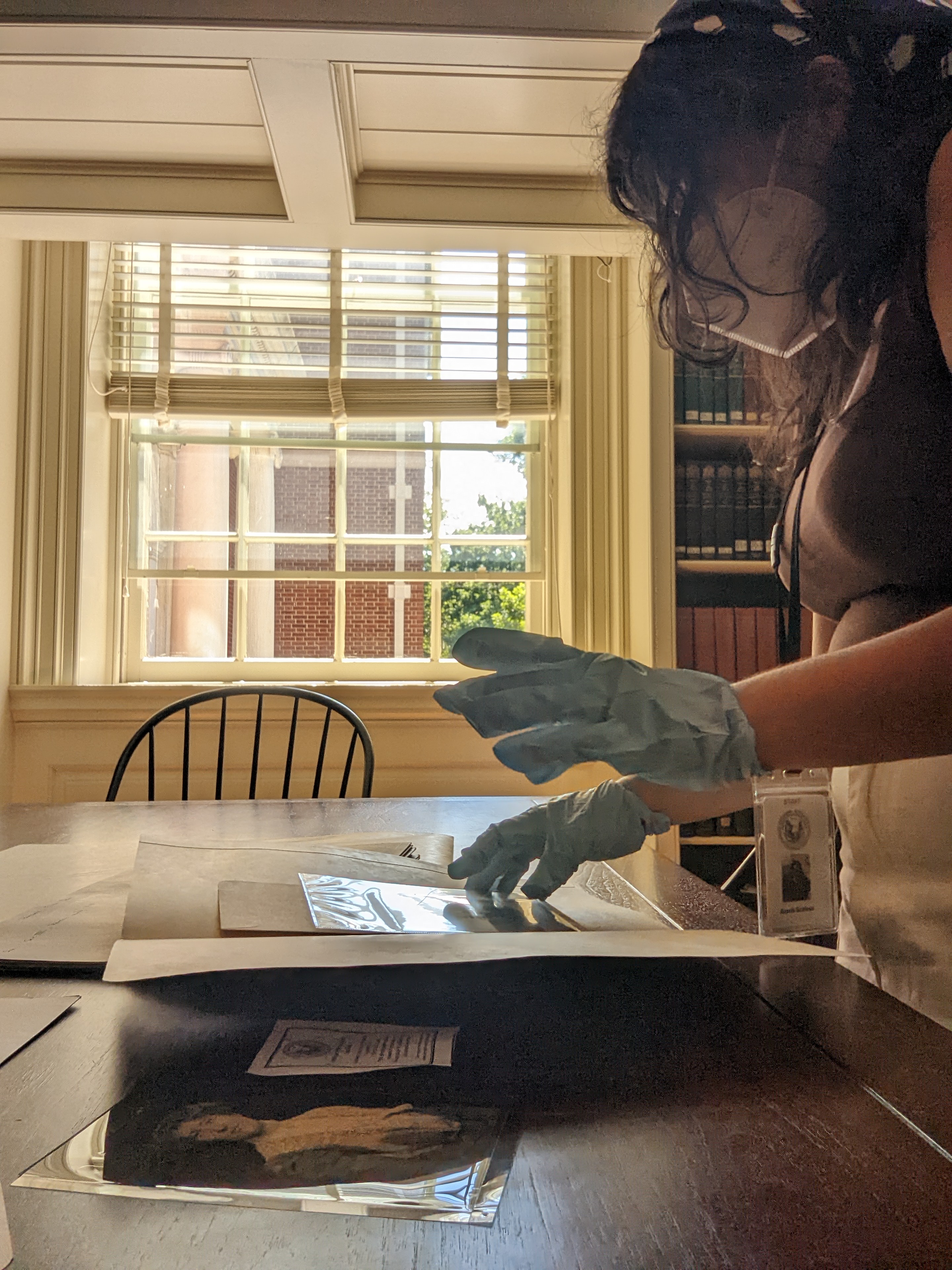

Since these paintings are at the American Philosophical Society, I spent most of my research time at the APS physically digging through and reading materials from the Parsons Collection. The collection’s finding aid is extensive and the physical collection includes over 38 linear feet of materials. The materials within the collection include: family photographs, field notes from her research trips, and correspondence between her mentors, students, professional and suffragist organizations, and a selection of unpublished manuscripts. Through my research, I was able to gather that Parsons was an anthropologist, professor at Columbia University, and a self-proclaimed feminist and suffragist who came from a wealthy family.

As I was browsing through the finding aid, I noticed one of Parsons’ unpublished manuscripts titled “Nursery and Savagery.” When I saw, I re-read the title to make sure I understood that I did in fact read the word “savagery.” Once I realized that “Nursery and Savagery” was in fact what the manuscript was titled, my stomach churned.

For those who may not know, the term ‘savagery’ is a derogatory, racist term used to dehumanize Indigenous people.

Despite feeling discomfort from the title alone, I decided to request the material to read in the reading room. I did this to get a better sense of the frameworks Parsons was working under while conducting her field research in Indigenous communities. In addition to trying to make sense of Parsons, I also requested this material because I plan to return to APS with staff from Isleta’s cultural center, Yonan An, to conduct a formal review of culturally sensitive materials from the Parsons collection. Because working with the Parsons collection during my internship made me feel uneasy, I wanted to create a project that would allow me to share my experience of reading materials included in it.

For my project, I wrote a series of poems titled For Now and Later which is composed of three different poems each written in response to different excerpts from Parson’s manuscript, Nursery and Savagery. There were many materials in the Parsons collection that made me feel uncomfortable. But I specifically wanted to write poems in response to “Nursery and Savagery” because it was the first material of hers that I read during my internship.

Although using poetry may seem like an unconventional method in sharing research findings, my approach to using poetry in this manner is grounded by critical texts in the field of Native and Indigenous Studies.

The first text that guides my work is Decolonizing Methodologies by Linda Tuhwai Smith (Maori). Her approach in centering Indigenous knowledge systems and incorporating them into research practices is seminal to my own project.

The second text that grounds this project is Layli Longsolider’s (Oglala Lakota) poetry collection, Whereas. In the second part of her text, Long Soldier writes in response to President Obama’s 2009 Apology to Native Americans. My project draws on Longsoldier’s choice to write poems in response to a document and to use poetry as a way to show the impact documents have on Native people.

The third text that is fundamental to my project is Leanne Simpsons’ book, As We Have Always Done. Simpson’s text is a prime and empowering example of how research can be led by traditional knowledge and personal experiences. For me, Simpson’s text demonstrates that Native peoples can do research about ourselves and our communities because our ways of existence are worthy of taking up space within the realm of academia and research.

With my poems, I hope to illustrate the knowledge that I carry as a Pueblo woman into the archive when working with materials from the Parsons Collection and my response to Parsons’ work. Creating this collection of poems was a special experience, as I have never used archival materials to produce research that takes a creative form. With my project, I hope that folks can get a sense of what a Native person’s experience may be like working with materials in an archive.

Each of the three poems that follow is paired with a passage from Parson's Nursery and Savagery:

![Like Savages, children [too] have their ritualistic food. I suspect that cake, candy, and ice cream, lemonade, tea and coffee all mean something to them besides a pleasant taste. Wine certain[ly] does. To drink it means that they have passed from one age glass to another-whether or not they promise Father not to touch it until they are twenty-one.](/sites/default/files/inline-images/ParsonsQuote1%20%28Poem_%20_A%20recipe%20for..._%29%20%281%29.jpg)

A recipe for savage food, the savage way

Take your freshly ground, beige, bleak, boring, stale masa into both hands

lick your right hand like a dog grooming

appreciate the soft play-dough texture

press both sweaty hands together

forming a

round face of a laughing auntie as she

washes each husk, and drinks the dirty, starchy water

ridden with insect carcasses from the GMO cornfield far past the East mountains

A handful more,

grab a bright yellow husk, strings like the long hairs of a savage

three sisters

corn tassels

hanging

using only the tips of your brown fingers, press the dough into the ridges of the husk

Intentionally,

as if you were murdering a gringo, but peaceful and docile as they force you into a box

cramped, tired, breathless, suffocating while

feeding the guests after dancing

in the scorching solar flames

to the pounding beat of

delicately placing the peeled green chiles picked from a garden of dust and weeds

mixing them with meat from a pig skinned alive nearby

on top of the soft mesa

using your hands once more,

roll the tamale like a cigarette purchased at Zuni’s by your uncle

ensuring a cylindrical shape like a plastic bottle floating along the Rio

Take an unused husk and tear into two large strips

So wide, a yucca leaf could not compare to the size

And tie a knot,

like the knots used in 1680 against the Spanish

hung above the fire, burning

On each side.

The ritual way.

Unable to break away, passed on,

- Nursery and Savagery pg 3

Gasping for Green Chile Air

savage Restrictions make me think of

a sash pulled so tight around your waist you suffocate

while laughing with your cousin before the Feast dance

Or, the honorable duties of a Pueblo woman

the gracious, delicate wrapping of the supple, white, elk skin moccasin

the caretakers of the young ones,

the make-sure-you-come-home-before-sundown ones,

the gossiping and laughing until the tears of down their eyes flows like the rio,

the bearing of knowledge so powerful the Spanish coward

Without shame, without worry of the rest of

At the possibility of a world where rules defy

the dos and don’t of colonial society

of oppressive structures

permeating into our temperate adobe homes

like the fracking of the land below

contaminating our ways of life

Savage Rules, Savage Ways, For The Past is Now

A suffragist you say, one who fights for women’s rights

Misunderstanding

Between us

Rules

of life divide us

Oppression

seemingly opposing

Rules, limiting you from access and understanding

The dynamics between us and the sacred,

a boundary, a line, a division, a gate, a barbed wire fence

Between the sacred and you

Far away from understanding distance

Of rules, of regulations, of oppression, of laws, of

Boundaries.

Knowledge to be known to those who understand and those who don’t

Rules, divisions forced upon by greater forces of colonialism

A parasite into the ways, limiting our women,

making them susceptible to violence

Matriarchy is sacred.

Rules of matriarchy take form in the abundance of love

of food

of drink

of cooking

a sip, a swig, a nourishing splash of fresh water from the river that flows through

like the knowledge of elders, the storytellers, the medicine men, the history keepers, the

knowledge bearers, the matriarchs.