The Hunt for a Better Solution

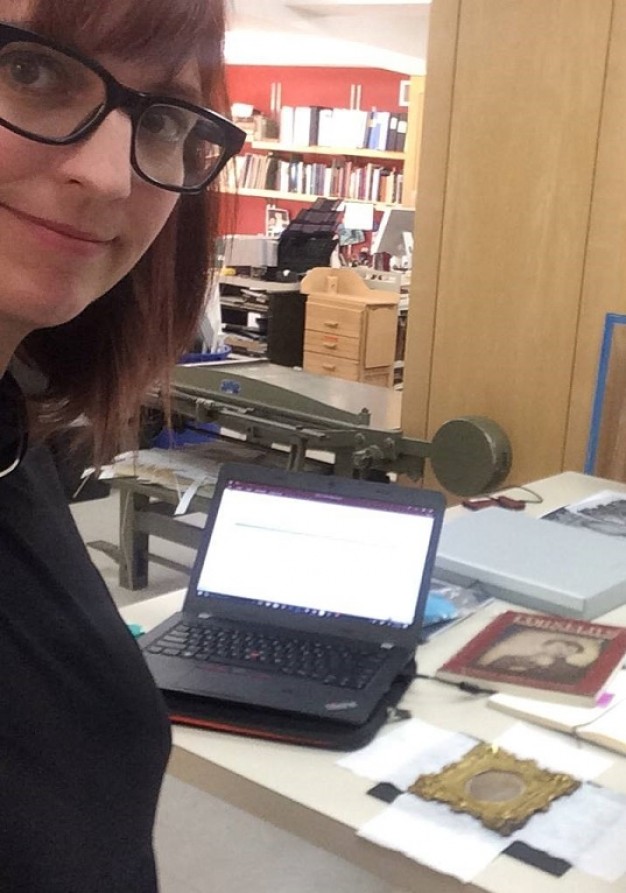

I recently had a visit from one of my favorite photograph conservators—Rachel Wetzel of the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts. Rachel’s been working with us at the APS since 2015 to document and preserve two of our most precious daguerreotypes—portraits of Paul Beck Goddard and Peter Stephen DuPonceau. These luminaries were photographed by Robert Cornelius in Philadelphia at the dawn of photography.

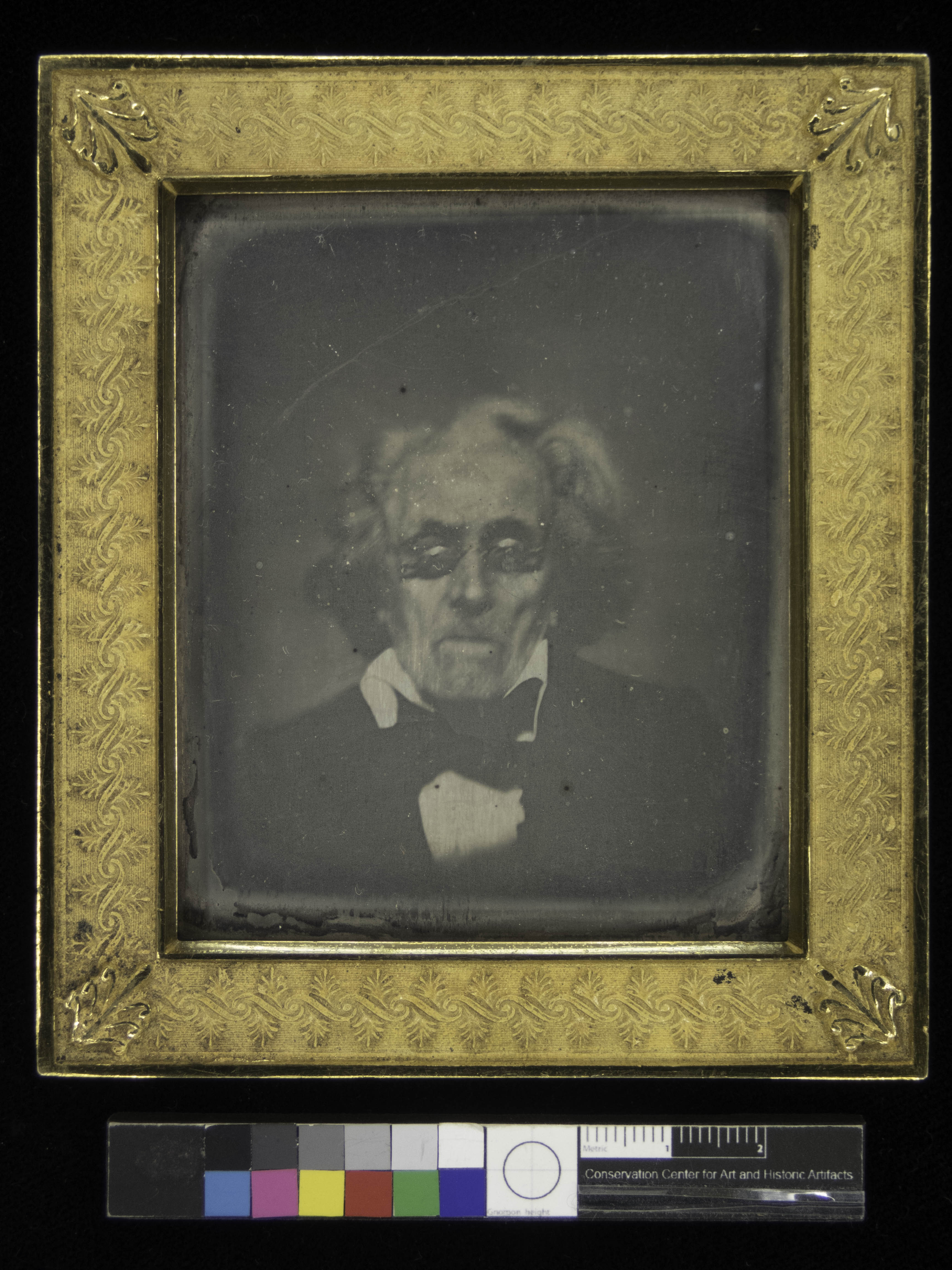

These photographic plates had undergone cleaning with thiourea—a common 20th century silver cleaner—in 1978. Residual chemistry left the plates with a white haze that obscures the image, and places the portraits at risk from increased damage over the years.

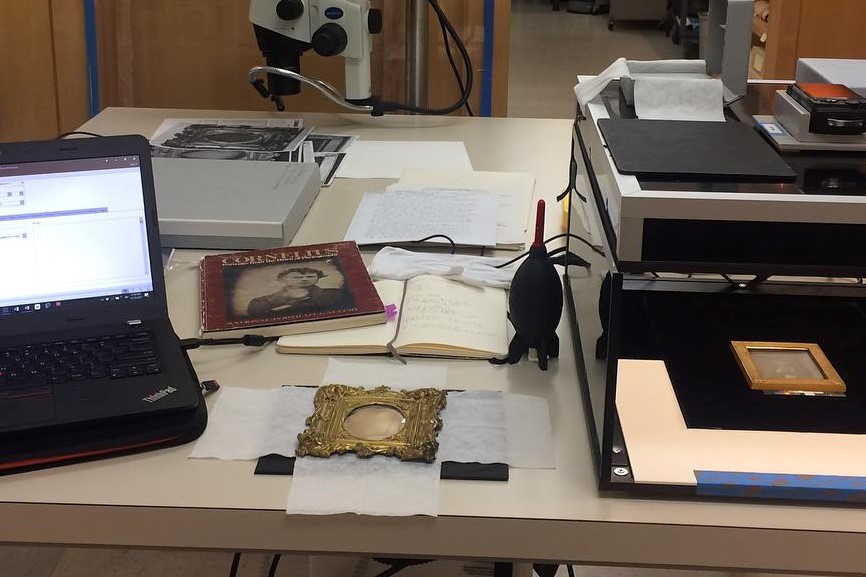

Rachel’s goal, along with her international team of daguerreotype experts, is to create mock-ups to replicate of quirks of Cornelius’ most early daguerreotypes. The mock-ups will be subjected to thiourea, after which Rachel and her team will attempt to clean the thiourea from these plates without damaging the image.

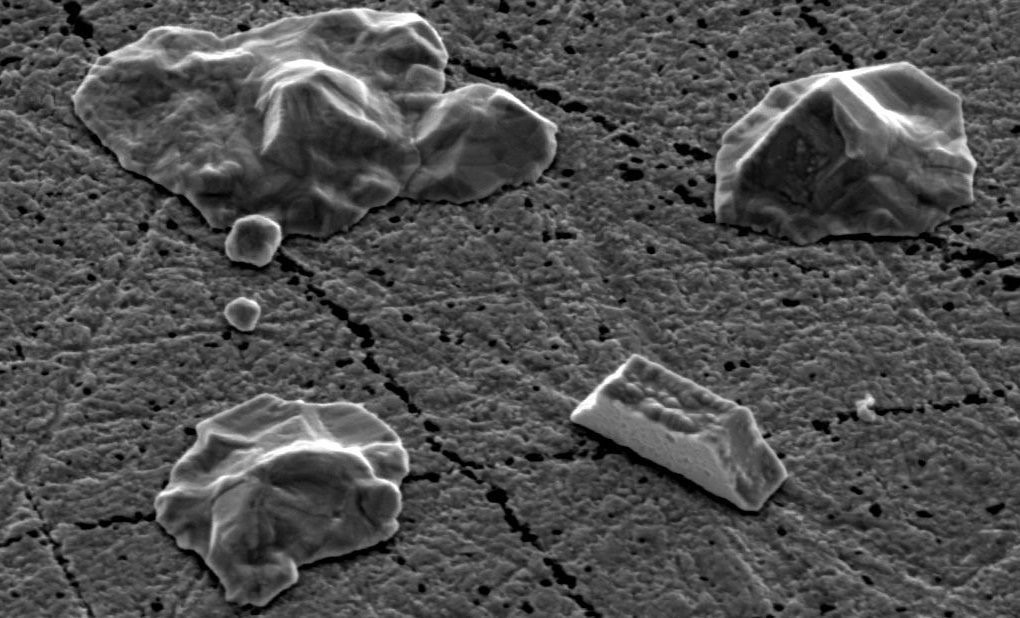

Rachel reports steady progress on this front: the mock-up plates have been made, and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of these plates yielded data about the plates’ surface topography, chemical composition and crystalline structure. The plates were artificially aged, producing a tarnish film that replicates a tarnished daguerreotype from the 19th century. A second round of SEM imaging followed.

Next, Rachel and “Team Cornelius” will clean the tarnished plates using historic cleaning solutions, followed by another SEM round. They expect that the historic recipes for cleaning will damage the plates in much the same way our two Cornelius works were damaged. This will give the team data to enable them to study the damaging effects of these solutions, with the hope of finding a way to safely clean these mock-ups. Ultimately, this study will produce a safe way to perform conservation treatment on our two treasures.

Simultaneous to this study, and in order to collect as much pertinent info about these early photos as possible, Rachel is creating a database (funded by the National Endowment for Humanities) which aims to collect all known Cornelius-produced daguerreotypes. As a part of the database, she is photographing the daguerreotypes with a specially created traveling photo studio. The mirror-like finish of the plates is challenging when attempting to capture an image; this system eliminates reflections that can obscure the plate’s image.

It’s important to note that conservation photography is typically very different from images one may view on the web. Our goal as conservators is to produce an exact replica of the image as it exists in real life: we attempt to simply document the item. This is why conservation photographs have a color rendition chart and other markers inserted into the photo. Most other photography—for goals too great to enumerate—usually includes image enhancement, often to the extent that the photo-shopped image rarely looks 100% true to the original item.

In the end, this elaborate study is necessary because production of these exceedingly early and unique photos involved much experimentation and change over the first few years of photography. Due to individual inconsistencies, these early plates may not respond to a typical cleaning that would be successful in the instance of later daguerreotypes. Our hope is to find that singular solution.