The APS and Central Europe: A Bumbling Beekeeper from Bohemia

By Jonathan Singerton

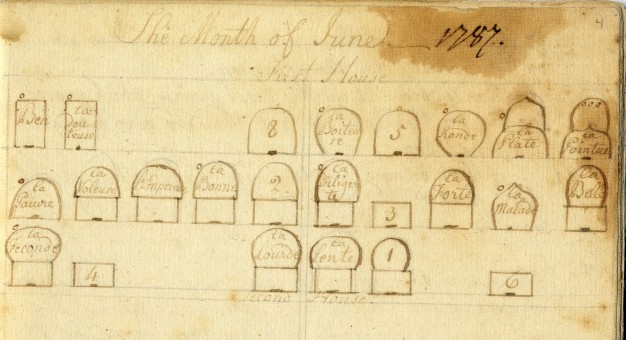

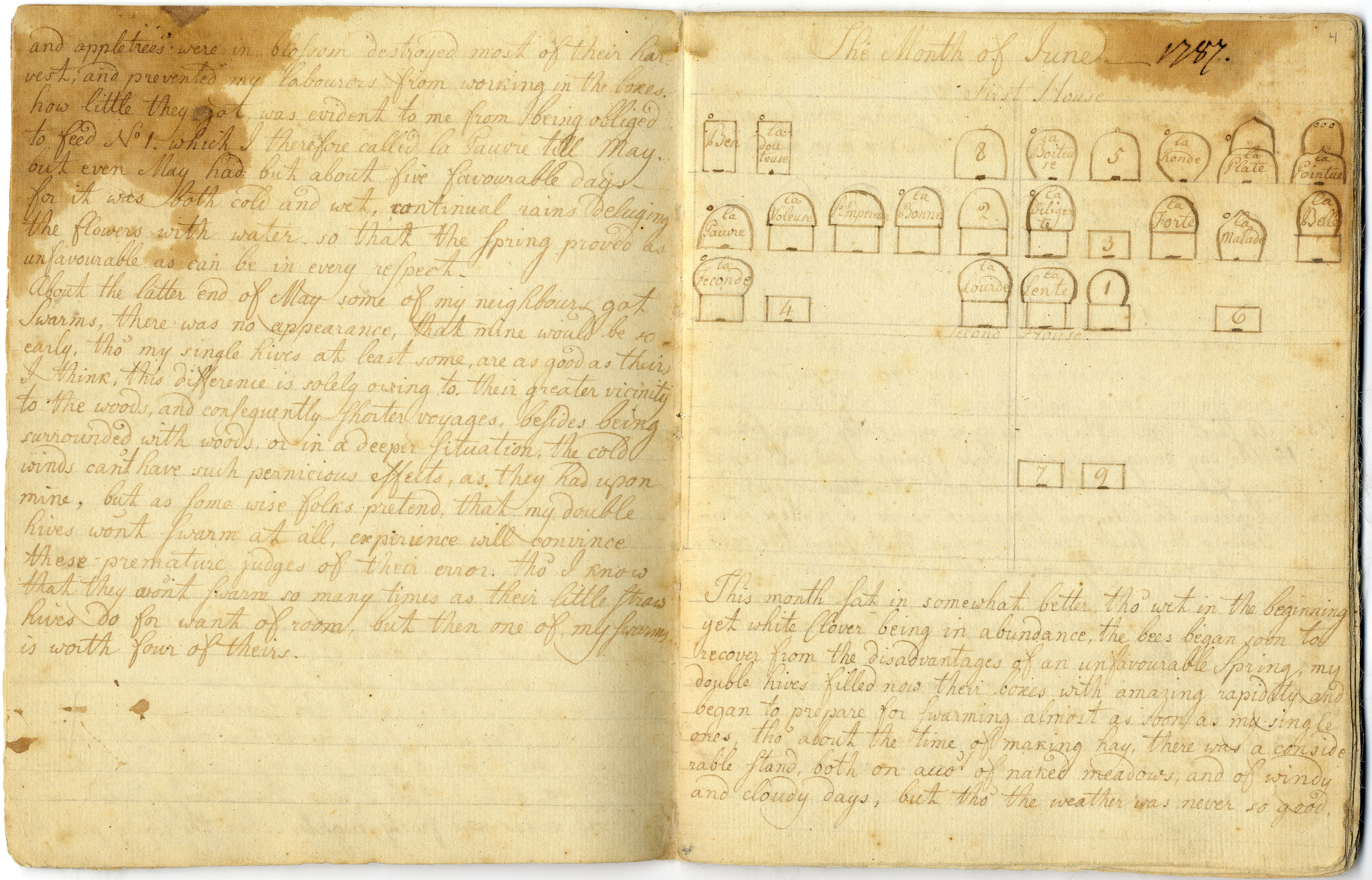

Image above: Detail of Donath’s layout of his hives, ca. April 1787, APS Digital Library

In March 1787, Joseph Donath (1751-1829) arrived at Spring Mill, fifteen miles outside Philadelphia on the bend of the Schuylkill River. Donath, a merchant in the city frequented his summer residence often but this year he decided to follow many of his friends into apiary. To learn and keep track of his new hobby, Donath kept a detailed journal from March 1787 to November 1788, which has been digitized and can be found in the Digital Library of the American Philosophical Society.

Born in northern Bohemia, Donath arrived in the United States in December 1783 as the representative of an Austrian textile merchant. His appointment came on the heels of expanding commercial interests between Central Europe and the newly independent United States. In September 1783 the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II sent an official trade delegate to oversee Habsburg interests in the United States since merchants across his realm were intent on expanding into North American markets.

Donath’s new position was a lucrative one since not only placed in him at the centre of activity but it came with a salary too. He likely obtained such an opportunity due to his political connections from his local freemason lodge in Vienna, the same one where Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was also a member. Upon his arrival in the then American capitol, Donath set up shop between the corners of Market and Chestnut Street and reported back on sales directly to the government in Vienna. However, it became clear that any long-term trade between the Habsburg Monarchy and the United States would require a favourable deal to reduce tariffs and boost Central European exports. By 1787, talks between Thomas Jefferson and the Habsburg ambassador in Paris had broken down. US-Habsburg trade, including Donath’s business, effectively collapsed.

Downtrodden and perhaps in need of a break and a new venture, Donath began his journey to Spring Mill in March 1787. Although Donath was a merchant by trade, his apiary journal details his endeavours in trying to break into the apiary business and community. He suffered some teething problems as, he recorded bitterly, local apiarist vendors inflated their prices when selling him starting bees and hives. By mid-March 1787, Donath managed to secure twenty-four hives of “tolerable quality” for the considerable sum of $525.

Donath’s journal is replete with sketches of his various hives, each allocated a name, and details about their arrangement. He even gave them names. Yet as an inexperienced practitioner, Donath suffered ruin over the harsh winter of 1787-1788 and lost seven hives. After several absences from recusing his beleaguered stock, Donath returned to Spring Mill in mid-August 1788 to find his remaining bees had all but died from “invasion and a lack of food.” He quit shortly afterwards. Despite the failure of his experiment in beekeeping, Donath produced around fifteen gallons of honey which he likely tried to sell back in Philadelphia.

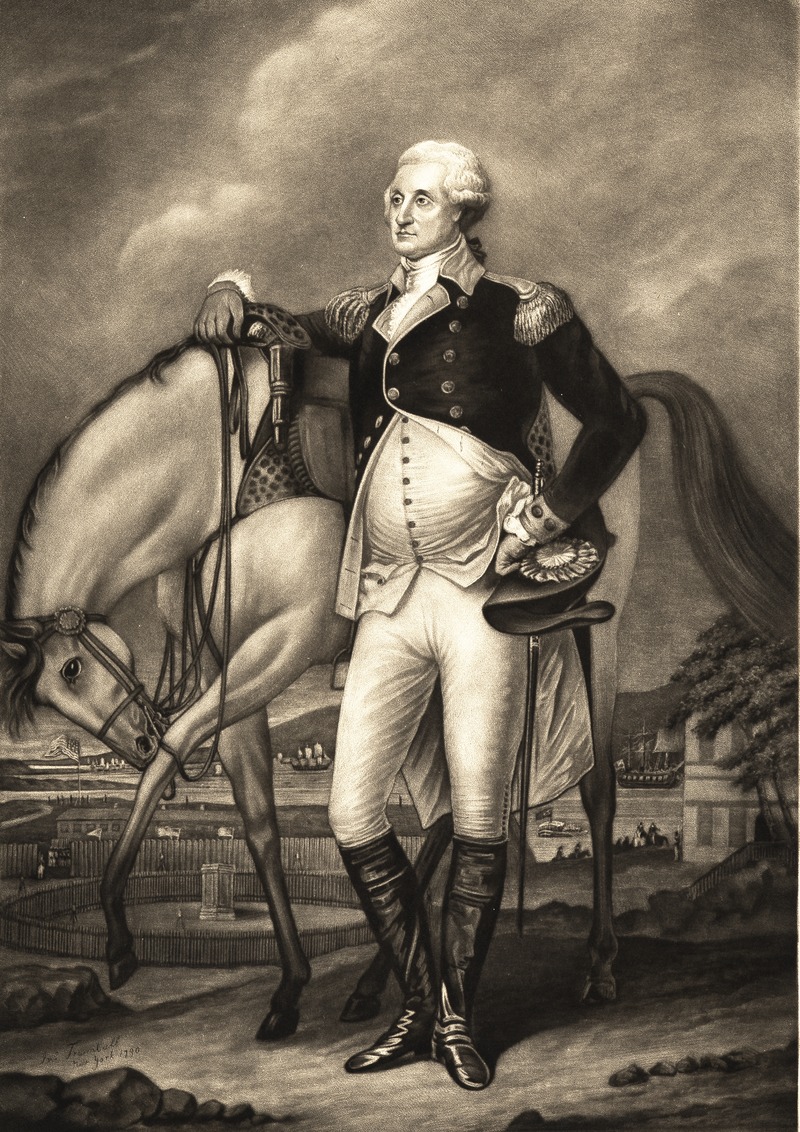

Donath’s journal holds many more insights beyond the details of his beekeeping escapade. It is clear the journal already tells us about his mercantile state after the collapse of US trade with Central Europe. One highly significant detail is Donath’s account of a visit by George Washington on July 22nd 1787. Washington was in Philadelphia for the Constitutional Convention but visited Spring Mill and bought some honey from Donath. As a wealthy plantation owner, Washington may have been inspired by Donath’s attempts. Less than a week after his visit to Donath’s budding apiary at Spring Mill, Washington began his own apiary at Mount Vernon.

Donath’s journal is also part of the wider eighteenth-century attempts harness and to profit from nature. Beekeeping, especially in during the Age of the Enlightenment in the New World, was a widespread obsession. The eighteenth century was awash with books and manuals on the topic. French traveller John Crévecoeur noted the popularity in his Letters from an American Farmer and as Tammy Horn notes, beekeeping symbols pervaded early American society from banknotes to calling cards through the colonies. To the eighteenth-century mind, bees and their collective beehive symbolised industriousness and fraternity. Donath, as a merchant and a former freemason, probably knew the social status that could be derived from his leisurely pursuit in such an enlightened pastime.

A rich journal with connections beyond the humble venture on the banks of the Schuylkill River, Donath’s journal holds illuminating insights into the commercial and intellectual world of the early republic and holds value for historians of science and the environment.

Jonathan Singerton is a historian at the University of Edinburgh currently defending his doctoral thesis 'Empires on the Edge - The Habsburg Monarchy and the American Revolution 1763-1789' which looks at the transatlantic diplomatic, economic, and intellectual links between Central Europe and the early United States. He is also writing a biography of an Austrian noblewoman who lived on the American frontier around the same time. He is interested more widely in global approaches to the Enlightenment and the Age of Revolutions. In 2016, Jonathan visited the APS Library to conduct research in the Benjamin Franklin papers and other collections for his dissertation research. He can be reached via Twitter (@JonSingerton) or via his professional website.