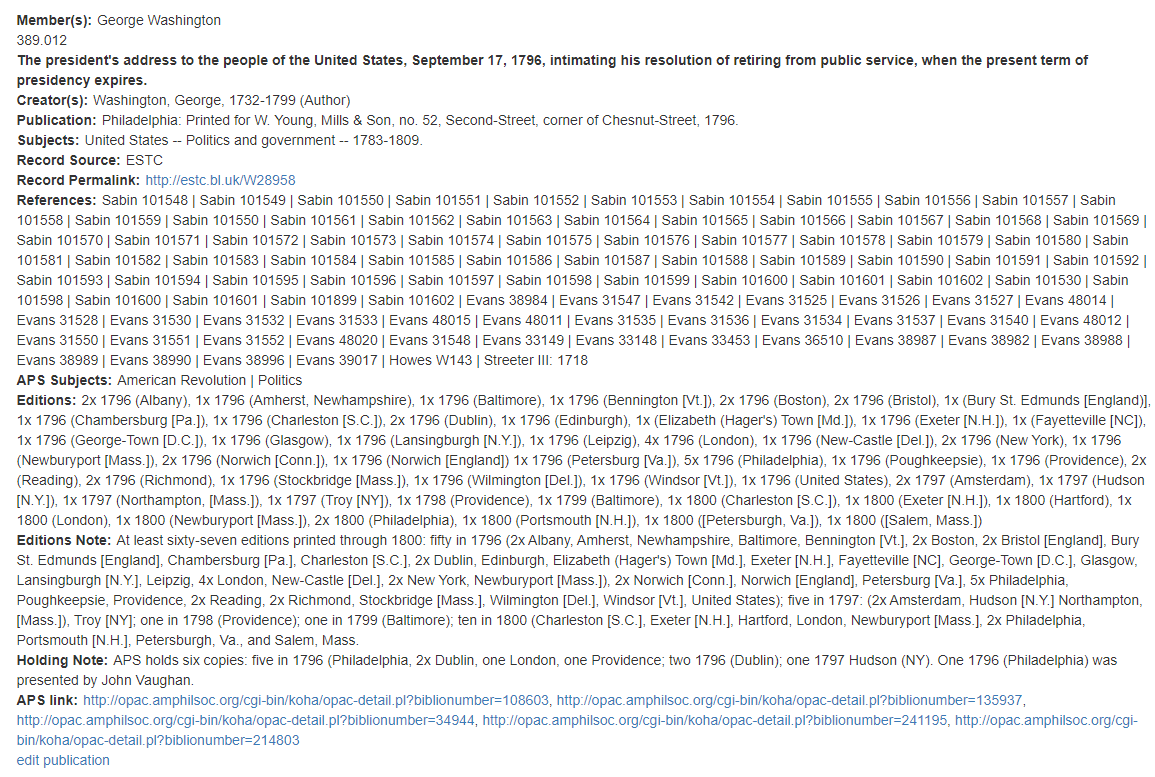

APS Fellow Julie Fisher has taken on the task of transcribing early minutes of the APS, covering between 1774 and 1787. Her transcriptions, or copy of what was documented in these written records, will present, for the first time, an unabridged edition of the Society's early meeting minutes. Not only does this edition provide a new way to examine or interrogate the Society's early history, it also allows the opportunity to align these records with current standards. This project ends up covering both history content and historical research skills through the minutes themselves and the process of transcribing, respectively.

About the APS

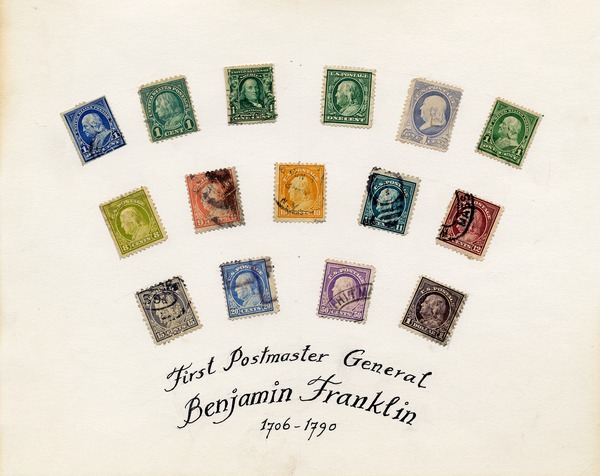

“The first drudgery of settling new colonies is now pretty well over,” wrote Benjamin Franklin in 1743, ''and there are many in every province in circumstances that set them at ease, and afford leisure to cultivate the finer arts, and improve the common stock of knowledge.” The scholarly society he hinted at here became a reality that year, in the form of the American Philosophical Society (APS). The dual influences of Franklin and the Enlightenment along with the needs of American colonists led the Society to pursue equally "all philosophical Experiments that let Light into the Nature of Things, tend to increase the Power of Man over Matter, and multiply the Conveniencies or Pleasures of Life." At the time of its founding, natural philosophy, the study of nature, comprised the kinds of work now considered as science, technology, and the humanities. Early members included doctors, lawyers, clergymen, and merchants interested in science, and also many artisans and tradesmen like Franklin. Members of the APS encouraged America's economic independence by improving agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation. Notably, however, this group was largely limited to white men of wealth and privilege.

The period covered in this project, 1774-1787, comes after a period of fits and starts for the Society. It wasn’t until after the 1769 Transit of Venus that the Society really achieved international status and acclaim. The scientific endeavor of mapping the path of Venus across the sun was led by prominent Member, David Rittenhouse. With one of his telescopes, erected on a platform behind the State House (now Independence Hall), he successfully marked the celestial pathway during this rare phenomenon. Achieving this large feat and coordinating the American efforts, he successfully attracted the recognition of the scholarly world.

This achievement led to the revival of the APS during the American Revolution. Francis Hopkinson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Samuel Vaughan, a recent immigrant, led the APS through this era of growth. In 1780, Pennsylvania had granted the APS a charter guaranteeing that the Society might correspond with learned individuals and institutions "of any nation or country" on its legitimate business at all times "whether in peace or war." This charter lends an international scope to the conversations of the Society, which is reflected in the minutes. The state also deeded to the Society a portion of present-day Independence Square, on which it erected Philosophical Hall in 1785-1789. The construction of this building brings in conversations and historical figures in Philadelphia that floated outside of the Society’s more scholarly crowd.

The Enlightenment’s influence on the Society's charter and the location of Philosophical Hall adjacent to the seat of government clearly illustrate how closely the new nation linked learning and freedom, regarding each as the support and protection of the other. Until about 1840 the APS, though a private organization, fulfilled many functions of a national academy of science, national library and museum, and even patent office. Accordingly, political figures and presidents often consulted the Society. The Society also served as the prototype for a number of other learned societies, and gave birth to organizations for agriculture, chemistry, and history. For many years the Society's hall provided space for the University of Pennsylvania, Thomas Sully's studio, Charles Willson Peale's Museum, and several independent cultural and philanthropic organizations. Thus, politics and the deeper histories of Philadelphia organizations are also revealed in these minutes.

About Transcription

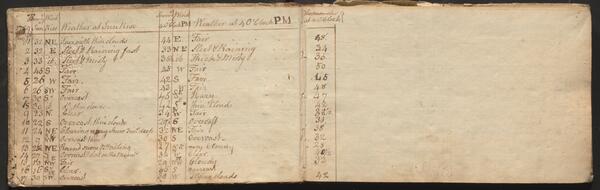

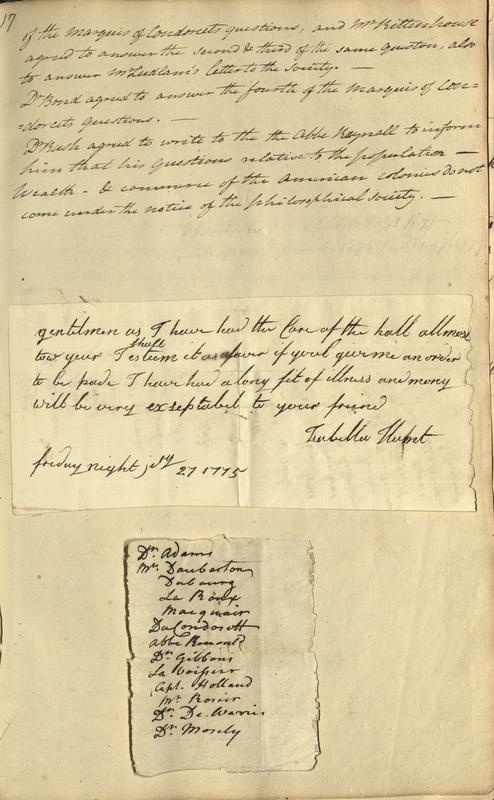

An original note found within the early minutes of the Society leaps into a conversation on the importance of updating transcriptions.

gentlemen as I have had the Care of the hall all most

tow year I shall esteem it as a faver if youl give me an order

to be pade I have had a long fit of illness and mony

will be very exseptabel to your frind

Isabella Hunt

friday night [jary] 27 1775

Skimming comes easily to researchers of all kinds, and it can be tempting to skip over difficult lettering or unfamiliar wording. Transcribing, however, provides no such refuge from the sticking points of the past. A transcriber must confront every strange turn of phrase, quirk in capitalization, or phonetic spelling. This practice of slow pacing is seemingly at odds with our reading habits today. What other benefits might this slowing down unlock for students? Notice the uneven line breaks, the misspellings, but also the content. A note like this would be among the items not included in the initial transcriptions of the minutes from the 19th-century. Historians today now see this as an essential piece of history. In order to copy a note like this, you have to read and write slowly, transcribing the text as it appears. This pace can connect the transcriber to the content more closely and in a more empathetic way than other types of reading.

Learners should begin to interrogate historical records, both published and in manuscript form, early on -- this is a skill that should not only be left to graduate students and scholars. A researcher’s emotional responses to manuscripts, the conditions under which the researcher is transcribing, should all be considered. After all, give two people the same manuscript to transcribe and you may get two different transcriptions. What impact might choosing one over the other have on future researchers?

Reading a heart-breaking petition in print can be sad enough; seeing such words put down in the petitioner’s own hand can pack an unexpected emotional punch. Most people from early America did not leave behind portraits, but the existence of such handwritten material can provide an all too rare glimpse into these lives, their emotions, educational level, and other personal details.

Overall, transcription, and ultimately archives like those at and of the APS, are concerned with access to the past, in particular, who has access to which pasts and whose pasts are easily discovered. Another point of access is created while transcribing though: access to the historical figures themselves. Sometimes that figure happens to be a learned society! The APS invites learners of all ages to explore the Society’s early history and gain essential history skills by trekking through the early Minutes.

Written by Dr. Julie Fisher, APS Fellow, with the assistance of Mike Madeja, Head of Education Programs