Sitting with the Washington Family

Header image: Edward Savage, The Washington Family, 1789-1796. Oil on canvas. 213.6 x 284.2 cm. (84 1/8 x 111 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art

While curating the exhibition Mapping a Nation: Shaping the Early Republic, lead curator Erin Holmes and I knew early on that we would put a bench along the back wall of the gallery. We could not put an object on the wall behind the bench where visitors would sit, but we did not want a huge empty space on the wall. We decided to make a large vinyl reproduction of The Washington Family painting by Edward Savage (1789-1796). The museum staff now jokingly refer to it as the “selfie wall” because we know that many visitors will see the image and think that it’s a great photo op.

But we chose to include The Washington Family for a number of reasons and we hope that it becomes a conversation piece. Apart from being a visually compelling image, The Washington Family illustrates a number of the themes and objects from the exhibition. Here is a quick summary of some of the connections between the image and the exhibition:

1. Perhaps most obviously, the Washingtons – George, Martha, and their grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis – engage with a map and a globe. Geography was an important subject for citizens to learn in order to understand their country and place within the world. Both men and women learned geography and how to read maps, so the first family of the United States was modelling good citizenship in this portrait.

2. We’ve placed the image between terrestrial and celestial globes. Globes, mostly imported during this period, were expensive mathematical devices and geographic tools. The globe in the image emphasizes the Washington family’s status and education.

3. Custis also holds a set of dividers, a drafting instrument used to draw surveys and maps. Two of these are on view in the exhibition. Throughout the exhibit we include various tools used by mapmakers to represent the processes of mapmaking and the power of mapmakers to shape our understanding of land and borders.

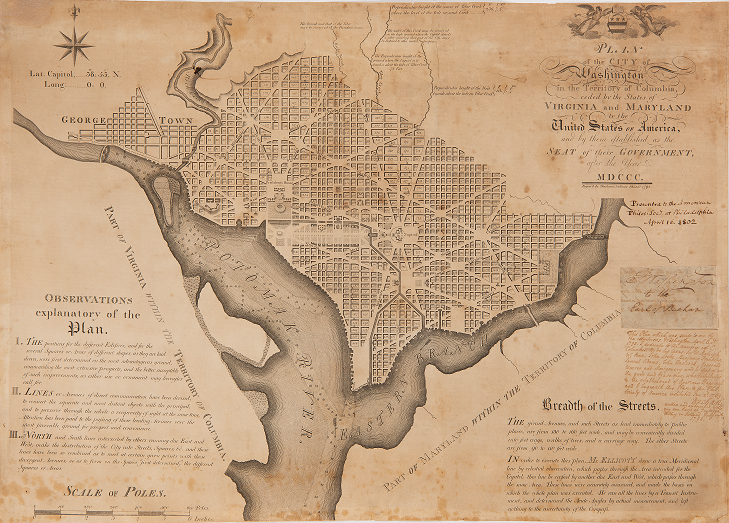

On display nearby will be George Washington’s personal copy of the Plan of the City of Washington, the same map that appears in The Washington Family. George and Martha point to land they had purchased in the federal city, a reminder of the land speculation going on during the early national period.[i]

4. A black manservant appears behind Martha. This man is often called Billy Lee, George Washington’s enslaved valet. However, the man depicted is not Billy Lee.[ii] Regardless, this unnamed man’s presence is a reminder of slavery’s existence in early America. Contributions of enslaved people and the role of slavery and the slave trade in empire- and nation-building are explored throughout the exhibition.

5. The black man’s marginal position in the portrait also represents the marginalization of people of color. The contributions of people of color to geographic knowledge, maps, and surveys often went unrecognized. Benjamin Banneker, a free black scientist who participated on the team surveying the federal city, is recognized by history and he became quite famous. But he was paid less than other team members and, according to an early biography, he ate separately from the white surveyors.

6. In the background is a view of the Potomac River filled with ships. Both the northern and southern shorelines appear. Washington, D.C.’s location along the Potomac was chosen because it was a geographically central site between the North and South. Regional tensions were heightened during this period and are explored through a number of objects in the gallery.

7. The Potomac River was also understood by many, including George Washington, to be a gateway to the West. It could link the capital city and the eastern seaboard to the Ohio River Valley, increasing trade. Interest in the West is a running theme throughout the exhibit.

There are many more things one could talk about when viewing this portrait, but hopefully this blog post provides a starting point for conversation and shares insight into the curatorial choice to reproduce it.

Mapping a Nation: Shaping the Early Republic is open Thursday-Sunday, 10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. until December 29, 2019. The APS Museum is located at 104 S. 5th Street.

[i] This “Easter egg” was recently pointed out by Ross Barrett in “‘Capital Likeness’: George Washington, the Federal City, and Economic Selfhood in American Portraiture,” in Beyond the Face: New Perspectives on Portraiture (National Portrait Gallery, 2018): 60-81.

[ii] The manservant was painted by Savage while in London. The model may have been John Riley, a free person working in London for the American ambassador. See the catalog entry for The Washington Family in American Paintings of the Eighteenth Century, pp.146-158 for more on this portrait.