Featured Fellow: Andrew Robbins, 2018–2019 Eugene Garfield Fellow

Each year, the Library at the American Philosophical Society hosts a rich intellectual community of scholars working on a wide-range of projects in fields including early American history, history of science and technology, and Native American and Indigenous Studies, among others. Read on to learn more about our fellows and their work at the APS. Additional information about our fellowship programming and other funding opportunities can be found here.

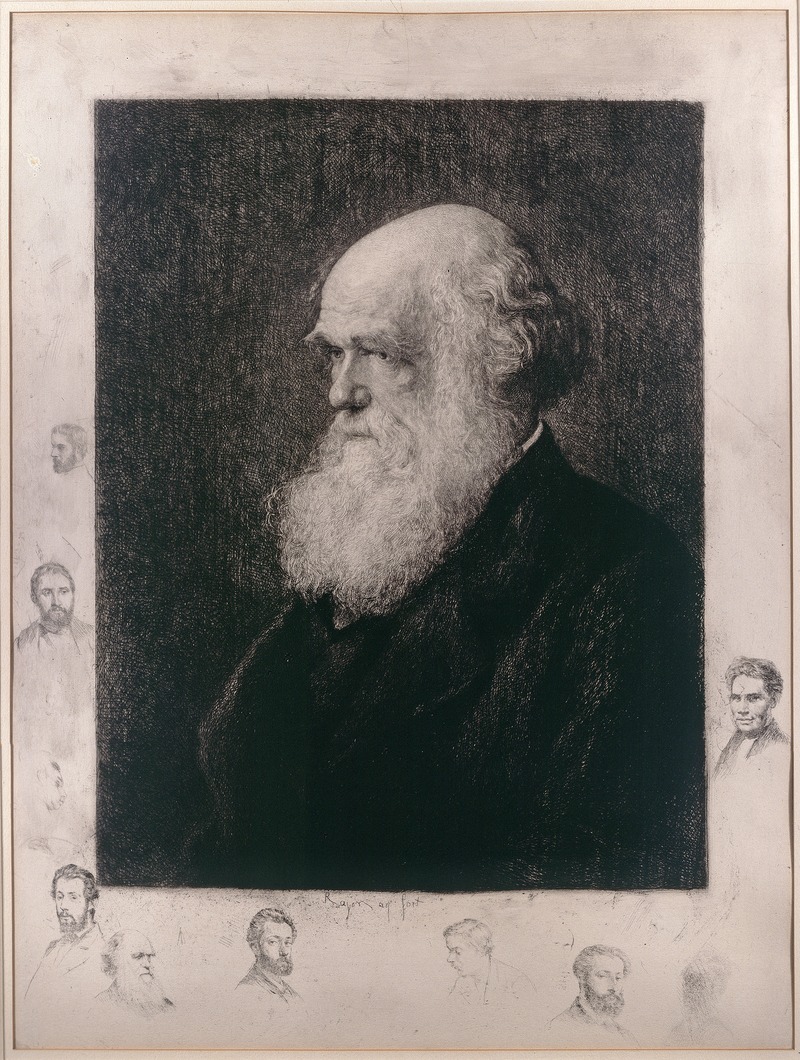

Project: “Struggling to Work, Energized to Die: Rhetorical Afterlives of Darwinism in Liberal-Era Italy”

Briefly describe your research project.

I came to the APS to get some broader context for my dissertation research, which is a cultural history of evolution in Italy at the turn of the century. It focuses on the rhetorical integration of evolutionary notions in the social sciences, literature, and the philosophy of science, all of which share a similar ambition to conceptualize Italian nationalism and to establish an Italian identity through the lens of Darwinism and Spencerian evolutionism.

What collections did you use while working at the APS?

Because my project is concerned particularly with the various afterlives of Darwin in Italy, I spent most of the time at the APS searching through printed materials in Italian, drawn mainly from the James Valentine-Darwin collection. Throughout the month, however, I studied anything that was written in Italian during my period of focus (1860-1930), some of which came from the library’s general print collection. The APS also houses a vast collection of journals, documents, and books on the electrification of Italy, which I found intriguing and hope to return to one day.

What’s the most interesting or most exciting thing you found in the collections?

Aside from the significant differences I found between the Italian-language editions of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (from roughly 1864-1932)—differences which were contingent upon the year of publication or the motivations of the publishing house—I found many other exciting tidbits at the APS. For instance, in a pamphlet on the proceedings of the African Society of Italy from 1885 (a society formed to debate the colonization of the African continent in competition with other imperial powers), I came across a speech that uses evolution to justify Italian imperialism—something I had hoped to find. Moreover, in a calendar of Darwin’s letters, I was able to trace Darwin’s entire written correspondence with Italians, which revealed many amusing, yet useful facts about Darwin and his Italian interlocutors. Finally, I did not anticipate when I began my residency that I would be so engrossed by the writings of Giovanni Canestrini, a naturalist who became the original translator of Darwin and one of his principal proponents in the Italian scientific community.

Do you have any tips or suggestions for future fellows or researchers?

I have three sound pieces of advice:

- Plan your time efficiently! There are too many interesting materials at the APS and too few hours in a day to look at all of them.

- Talk to the library staff as much as possible and make them show you the collections and stacks. Their knowledge is so intimate and extensive that you might discover something you never would have considered reading. And you’ll make some friends.

- Attend the brown bag lunches. I was always pleasantly surprised by what I learned from the speakers.

Any suggestions for must-see places or things to do in Philadelphia?

I was commuting, so I only saw endless construction on the highways or the inside of parking garages. But I hear Philly’s art museums are amazing.

Andrew Robbins is a PhD student in Italian at Rutgers University.