Fish-Fanciers: William T. Innes, Home Aquaria, and the Rise of Fish as Pets in Modern America

Header image: The September 1913 cover of William T. Innes's long-running periodical, The Aquarium

Fish and marine mammals have long been central to the work, culture, and caloric content of Americans. The Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Coast, for instance, sustained themselves for centuries on the prolific salmon of the Columbia River. Euro-American settlers found aquatic animals no less valuable after their mass migration to North America. Generations of Euro-Americans made their livings feasting on the unusually biologically productive—but sadly now greatly depleted—portion of the Atlantic Ocean located off the coast of New England and Eastern Canada. Euro-Americans also relentlessly hunted Atlantic and Pacific seals, driving the latter nearly to extinction. Ultimately, Euro-Americans took a greater biological toll on sea creatures than the peoples that they violently displaced. The technologies of industrialization and the ideology of unchecked capitalism allowed for natural resources to be extracted and consumed at an unprecedented clip in the 19th century. This led to a “sea change” in American attitudes toward marine animals in the late 19th century, the ramifications of which historians have only partially explored.

The dwindling of marine resources prompted novel conservation and restocking efforts. The most significant of these was the 1871 creation of the US Fish Commission (USFC). Congress originally created the USFC to investigate America's declining fish populations, but soon directed the organization to resupply American waters through human intervention. This unprecedented endeavor involved the artificial propagation of tens of millions of native fish along with the introduction of several non-native species to American waters. The USFC’s activities, as well as Progressive Era international treaties limiting fish harvesting and seal hunting, enjoyed considerable, but only partial, success in stemming the long-term decline in food fish resources that we still live with today. A much less noticed effect of the changing cultural mores of Progressive Era America, though, was a rising appreciation of the intrinsic worth of animals and their potential as companions. The first dedicated animal protectionist societies sprung up in the northeastern states in the years after the Civil War. Meanwhile, American pet-keeping became a mass phenomenon. Originally focused on birds and dogs, by the early 20th century, Americans had begun acquiring fish, many of them tropical, for home aquaria.

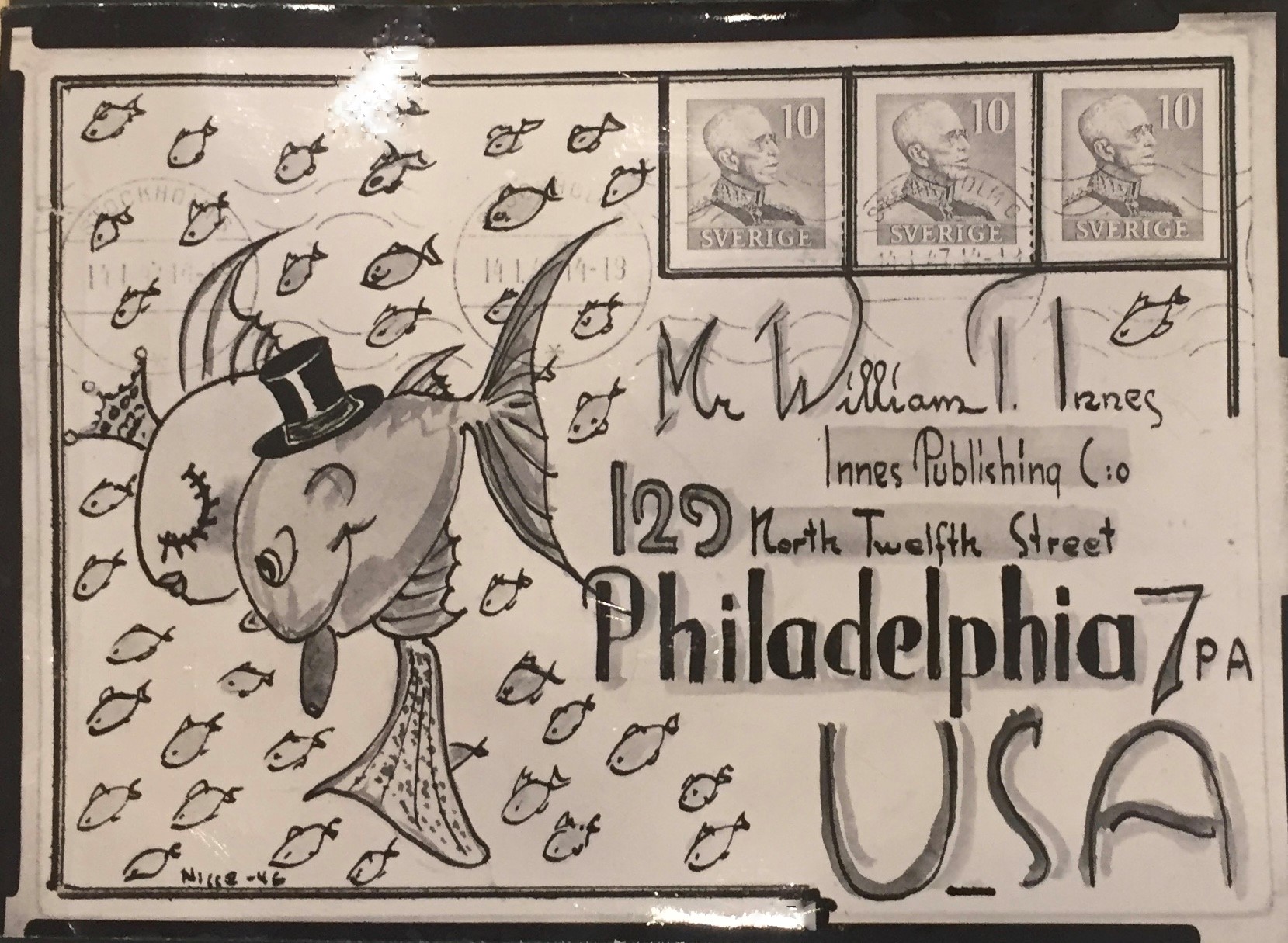

The American Philosophical Society’s William T. Innes Papers (Mss.B.In6) provided a unique aperture into this understudied subject. This voluminous collection, spanning the first 70 years of the 20th century, charted Innes’ long career as an aquarium hobbyist and editor of The Aquarium, a long-running Philadelphia-based periodical with national reach. Through it, one can glimpse the growth of the American consumer market in tropical fish—which exploded in the 1930s in particular—and the mechanics of the industry. Tropical fish had to be brought from abroad, usually from the Amazon River, to American homes. The long trip—from fishers to shippers to retailers, before finally reaching consumers—often resulted in high levels of fish morbidity and mortality en route.

Yet the collection focuses on Innes’ views on aquaria best practices and his friendly correspondence with many merchants, scientists, and enthusiasts—not the effects of the pet fish trade on the animals. The Innes Papers are often whimsical and humorous, too. One writer dubbed Innes “Mr. Tropical Fish,” a sobriquet he seemed to have liked. A 1937 letter from the professional wrestler Monroe Wells clearly tickled Innes, too. Wells told Innes that he had had a special ring robe made by the Tropical Fish Fanciers of Houston, and inquired “Have you ever heard of such a combination as a wrestler and a fish-fancier?” Innes replied in good humor, informing Wells that he was a wrestling fan.

Such levity, though, should not obscure the occasional insight the collection gives into the impact that mass commodification as pets had on fish. Innes lamented in 1944 that 100 million aquarium fish die every year, mostly because of consumer ignorance leading to poor aquaria maintenance and the grouping together of incompatible fish. There is also evidence that America’s vast consumer appetite caused problems abroad—the ichthyologist and Innes correspondent George S. Myers reported that Brazil temporarily banned the export of Amazonian fish in the 1940s. Ultimately, the Innes collection highlights a paradox at the heart of American petkeeping. Americans’ interest in fish as pets indicated the increasing socio-cultural value of animals, and their penetration into the familial sphere. But the mass consumerism of the pet animal trade had—and still has—a lot in common with extractivist 19th-century fishing, even if the pet trade's exploitative side is less obvious.