Back to exhibits

|  Back to exhibits |

Social and technological change

|

The technological changes in anthracite mining in Schuylkill County also sparked social change among its residents. Into what had been a predominately German and English farming community came an influx of Irish, Welsh, and English immigrants lured by the prospect of employment in the expanding coal industry. These ethnic groups brought with them from the old country different customs, experiences, and beliefs that influenced the course of their lives in their new home -- and in some cases led to ethnic conflicts, often violent, particularly between the Irish and the Welsh. Although they shared common Celtic origins, the Irish and Welsh found themselves separated by differences in religion, prior mining experience, and potential for advancement in the mining industry. The mix of differences proved as volatile and explosive as mine gases.

|

of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Co. |

On the rare occasions that historians devote more than a passing mention to Pennsylvania coal region history, the Molly Maguire story takes center stage. Said to have been a semi-secret organization of Irish workers who during the 1860s and early 1870s resorted to violence to attain their goals, at the extremes, the Molly Maguires have been portrayed either as heroes of the American labor movement or as terrorists persecuting law-abiding citizens. Both perspectives contain elements of truth, but both overlook the complexities involved. Inevitably the Molly Maguire story is refracted through the lenses of prejudice against the Irish, a tradition of retributive justice among the Irish, ethnic conflict and its effect upon workers' attempts to organize, draft resistance during the Civil War, conflict between labor and management, and the struggle between small-scale and large-scale coal operators.

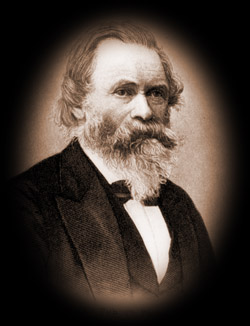

During the Nativist years of the late 1850s, Benjamin Bannan, editor of the most influential newspaper in the region, The Miners' Journal, had begun to use his paper to criticize Irish violence. At the time, the Irish Catholic population of Schuylkill County was soaring both in number and political power, and staunch Republicans like Bannan perceived the growing numbers of largely Democratic voters as a threat. Many native-born citizens expressed their outrage at what they saw as local "Irish" officials who ignored rampant disorderliness and violence committed against law-abiding citizens. Ironically, Franklin B. Gowen, born to an Irish Protestant immigrant father, was among those accused of ignoring Irish crime during his term as Schuylkill County district attorney.

|

The Miners' Journal |

The Molly Maguire story began in earnest in the mid-1860s when Gowen, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company, asserted that an organized band of Irishmen had plotted and carried out several murders of mining officials. Many Irish immigrants had known the Molly Maguires in Ireland as a semi-legendary vigilante group that had fought Irish landlords for tenants' rights. The group's name was said to derive from an Irish widow whose landlord had evicted her from her home. Gowen claimed that Irish immigrants to the Pennsylvania coal regions had transplanted a form of this organization and were employing the tactics they had used against Irish landlords against mining officials. Gowen's initial instructions to Pinkerton detective James McParlan included a directive to research Irish agrarian violence and vigilante organizations.

The conflicting emotions generated by the Civil War fueled the conflict, as many Irish immigrants aligned with copperhead Democratic resistance to the war and the draft. Opposed, in many cases, to aiding Blacks in any form, many Irish immigrants also objected to the war because, as non-naturalized residents of the country, they were expected to fight while they were yet unable to vote. For them, the war was a "rich man's war," symbolized by the ability of any draftee to buy exemption for $300 - any draftee, that is, with $300 to spare.

The simmering resentments boiled over during the summer of 1863. As New York City was prostrated by three days of racially-tinged "draft" rioting during July the Irish in Cass Township, Schuylkill County, also rioted. With a high immigrant population, the township had not met its manpower quota for the war, precipitating a call for draftees. Draft opponents went from mine to mine, recruiting men to block the trains carrying draftees from Harrisburg passing to Philadelphia. Benjamin Bannan, the draft commissioner at the time, resolved the conflict only by crediting the names of soldiers registered in Philadelphia to the Schuylkill County quota. Despite the prominence of Irish opposition to conscription, the proportion of Irish who served in the military was not significantly different than that of any other ethnic group relative to their representation in the general population.

|

Their interests coinciding, Gowen and Bannan both began to assail the "Molly Maguires" and to use allegations of violence and criminality for their own ends. By claiming that Irish workers were using violence to intimidate mine owners, Gowen and other mine owners, in complicity with criminal justice system, effectively squelched union organizing in the coal regions, and were able to rid themselves of their most vocal opponents. Believing that the Molly Maguires used the Ancient Order of Hibernians to conceal their violent activities, they set out to besmirch and destroy that organization as well.

In 1873, Gowen hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to infiltrate the Ancient Order of Hibernians, an Irish fraternal and beneficial organization that he believed concealed a violent terrorist organization known as the Molly Maguires. With the aid of evidence gathered by Detective, James McParlan, Gowen brought charges against dozens of Irish workers for crimes stretching back almost fifteen years to the murder of Frank Langdon, a man killed after speaking at a Civil War rally in 1862. The Miner's Journal enumerated fifty murders in Schuylkill County between 1863 and 1867, of which only handful could be attributed to Irish conspirators. These were, however, singled out as the handiwork of "the incarnate fiends who rule the County."

John (Jack) Kehoe, a former miner who had become a saloon owner and High Constable of Girardville was executed for the murder of Langdon in 1877. Kehoe was said to have had prior grievances with Langdon and reportedly stated at the rally that he would kill him. In all, dozens of Irishmen were brought to trial for murders and assaults committed in the name of the Molly Maguires, and at least twenty were executed. Kehoe, perhaps the best known of the men executed, received a posthumous pardon from Pennsylvania governor Milton Shapp in 1979 due to efforts of Kehoe's great-grandson, Joseph Wayne.

Controversy has surrounded the Molly Maguire story from the beginning. All agree that there were murders, but how many and whether the perpetrators and the accused were one and the same remains an open question. It is more certain that nearly all of the murder victims were employees of small coal companies rather than large ones, like the Philadelphia and Reading, which later took them over. Some historians have suggested that the presence of the Philadelphia and Reading's police force might have prevented murders of their employees, however others suggest that it is more likely that Philadelphia and Reading detectives provoked, or committed, the murders as a pressure tactic to persuade small coal operators to sell out. The end result is certain: a number of small operators were wholly consumed by the Philadelphia and Reading and a handful of other large corporations.