|

Fig. 24: East Prospect of Philadelphia

Engraving by Carrington Bowles, ca.1778 after George Heap, ca.1752 Courtesy APS

|

X. Inside Head's Shop (cont.)

|

Fig. 24: East Prospect of Philadelphia

Engraving by Carrington Bowles, ca.1778 after George Heap, ca.1752 Courtesy APS

|

1. "To a Chest of Drawers."

The earliest chest of drawers was also the earliest entry of any sort in Head's account book. In many respects, it was also Head's most significant chest of drawers: "To a feneared [veneered] Chest of Drawers," on 3/22/18, debited to James Poultis, at £8-0-0. It was the only piece of veneered furniture described in the account book.388

While there is evidence of veneered furniture having existed in Philadelphia at this period,389 surviving examples are rare,390 and tend to be of small size.391 Veneering had been a popular method of imparting a more sumptuous look to English furniture. Wood veneers, often of book-matched, highly figured walnut, were glued onto a carcass of less expensive wood, usually pine or deal.392 Given the sometimes extreme fluctuations in the Delaware Valley's temperature and humidity levels, and the fragile nature of veneer in general, it may have been difficult to maintain the appearance of such furniture in Philadelphia.393 Chipped or lost veneer no doubt helped relegate veneered furniture to less hospitable surroundings, such as barns or unheated attics, hastening their demise.

The abundance of walnut in the Delaware Valley gave solid wood an economic advantage over veneered production. Veneered furniture may also have become less fashionable in Philadelphia. Patrons wishing decorative chests of drawers could sate their desires with curled walnut or maple in the solid.394 The latter woods would have proved more durable than veneering. Head's customers of more conservative taste, many of them Quakers, would no doubt have been satisfied with pieces that were well-made, but not highly figured. Many of the case pieces from this era exhibit beauty in their proportions and turnings, rather than in their wood selection [fig. 3 & fig. 4]. This would have been in keeping with Quaker pronouncements against "superfluous furniture" and the desire for furniture "of the best Sort, but Plain."395

It is natural that Head's first recorded piece of furniture in America was veneered. Born in 1688, Head would have been about thirty at the time of his emigration. By that age, he would have long completed any apprenticeship as a joiner in his native land, and been fully conversant with its cabinetmaking techniques and styles. Therefore, he produced his first recorded Philadelphia furniture commission in a manner most familiar to him. But given the availability and relative cheapness of walnut in his adopted land, Head probably soon converted to the use of solid woods.

Head's cheapest chest of drawers cost Artha [Arthur] Jones £1-4-0. No wood was specified, but pine is a good candidate. While no "chests of drawers" were specifically noted as being of pine, simple "chests" of pine were usually priced at £0-14-0, that is, less than Jones's chest of drawers.396

Other chests of drawers appear in the account book at varying prices, but there is great consistency over long periods for certain prices, which leads to the conclusion that there were fixed prices for standard models.397 A comparison of these commonly priced objects, their frequency and the dates of their introduction, persistence, and last appearance, suggest that particular forms and models were produced at given periods by Head's shop.

The most numerous of the commonly priced chests of drawers were those at £3-0-0. Some 118 of them appear over the approximately twenty-year period from 8/22/20 to 9/28/41.398 Of that number, twenty two were debited two at a time, suggesting that they may have been ordered, and subsequently used, as pairs.399 But what did these chests look like? As none of the 118 entries for £3-0-0 chests of drawers specify wood, and because walnut was the wood Head received in greatest quantity and other woods were more costly, one may presume that they were of walnut.400 Also, the £3-0-0 chests of drawers probably stood on feet and not on frames. This may be deduced from the two debit entries, under the same date [10/3/23] for James Lippincot: "To a Chest of Drawers - £3-0-0/ To another payer apon a frame £5-12-0."401 The latter order might have been for a special form, consisting of a chest-on-chest-on-frame, or was a high chest. It does not appear to refer to two chests on separate frames. This is because Lippincot had earlier been charged only £6-0-0 for his orders of two chests of drawers at one time402 and £3-0-0 for the individual chest of drawers. Had those three chests of drawers each been on frames rather than feet, Head would have charged considerably more, as the making of frames was more labor intensive, and consequently more costly, than that of feet. Head charged Thomas Williams £2-5-0 alone, "To a fram for his Drawers."403

There are twenty five chests of drawers charged at £3-10-0, starting on 2/23/30, approximately a decade after the first entry for the £3-0-0 model.404 But as the £3-10-0 charge continued to appear until 10/23/43, a period roughly simultaneous to that remaining for the rest of the £3-0-0 chests of drawers, it cannot be said that it represents merely a price hike of an earlier model.405 As with the £3-0-0 chests of drawers, no wood was identified for any of the £3-10-0 ones, so one may again presume they were of walnut. The £3-10-0 chests of drawers possibly shared some of the other characteristics of the £3-0-0 model, but their additional cost may have been the result of their being larger or more complex. Were they larger, this would have required greater material cost. If they had more elements,406 this would have increased labor expense, such as for cutting dovetails on additional drawers.407 Alternatively, the £3-10-0 could have represented a chest of drawers with more up-to-date features, such as bracket feet, which may have been more costly to make than turned ball feet. The £3-0-0 model could have continued in production with older style turned feet to satisfy the taste of more conservative patrons.408 Like the £3-0-0 model, it is doubtful that the £3-10-0 chest of drawers would have had any support as elaborate as a frame, such as one might find beneath the chests of drawers supplied en suite with chamber tables. This is because for a chamber table on its own, Head never got less than £1-7-0, and generally £1-15-0 or more, and even his least expensive chest of drawers and chamber table combination cost £6-15-0, and generally £9-10-0 or more.409 Thus, a single chest of drawers on a frame would have cost at least £5-8-0, deducting the charge for the chamber table.

|

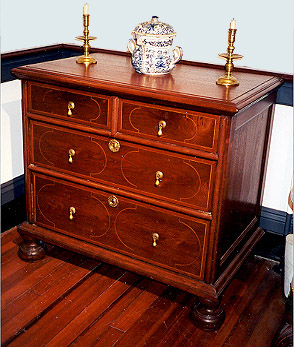

Fig. 25: Diminutive inlaid chest of drawers on ball feet

Chalfant Collection |

To recapitulate, the chests priced at £3-10-0 did not begin to be sold until roughly a decade after the first £3-0-0 model. The £4-15-0 and £5-0-0 models (if indeed there were such "models," as only three of each were sold) were sold at the beginning of the £3-0-0 production, although their sales petered out almost immediately.417 The £5-10-0, £5-15-0 and £6-0-0 models roughly coincide with the entire period during which the £3-0-0 model was sold. If one presumes that all of the foregoing were of walnut, their prices would not be a function of the type of material used. This would suggest that Head was simultaneously offering quite a varied line of chests of drawers, in terms of size or features, or both, during most of his cabinetmaking career in Philadelphia.

The term "high chest of drawers" was not recorded in Head's account book. The closest approximation was his "payer [of chests] apon a frame" for Lippincot.418 It is apparent, however, from the Head-attributed Wistar high chest of drawers and dressing table, and his entries for similar pairs, that the chests of drawers sold en suite with tables, as well as many of the other more expensive chests of drawers, were "high." "High chests of drawers" does not appear to have been a term frequently used in Head's era. The closest term I found in Philadelphia was "one high Pare [pair] of Drawers," in the 1750 probate inventory of cooper Samuel Powell.419 Hornor could not find "anything even suggestive of the word 'highboy' in Colonial lists, accounts or letters."420 The Richardson Family high chest is an example of a well-designed Willliam & Mary (early Baroque) high chest [fig. 7].

Above the £6-0-0 price range, the prices of Head's chests of drawers were seldom the same, suggesting that they may have been custom orders or models other than the previously cited models made in larger quantities at common prices. As Head started specifying woods other than walnut for chests of drawers priced at £7-5-0 and higher, the difference in price may have been a function of the wood cost. There are a total of fifteen chests of drawers individually priced higher than £6-0-0 (designated woods are parenthetically noted): one at £6-10-0,421 two at £7-0-0,422 one at £7-5-0 ("maple"),423 one at £7-10-0,424 one at £7-15-0 ("mehogany"),425 one at £8-0-0,426 two at £9-0-0 (one of "Charytre"),427 three at £9-10-0 (two variously noted as "Charitree" and "Charytree"),428 one at £10-0-0 ("mapel"),429 and two at £12-0-0 (noted as "mapel," to William Calender [Callender], on 5/19/37; and "maple," to John Leacock, on 12/22/37).430 Callender's chest of drawers may have gone to either his "house in Front street, above Arch street" or "his plantation at Richmond, alias Point-no-point."431 Thus, at least for the more expensive individual chests of drawers, it would appear that maple and cherry were more popular than mahogany, among woods other than walnut. None were of cedar. One reason for the lack of mahogany, other than matters of personal taste, may have been that the best of it was in short supply. Kalm reported that the "true mahogany, which grows in Jamaica, is at present almost all cut down."432

The highest price for a single chest of drawers was the £13-0-0 debited to one of Head's New Jersey customers, Thomas Shinn (1693-1753) of Burlington and Mt. Holly, on 10/24/31.433 No wood was designated. It was likely of maple or cherry, as Head was charging more for those woods. Moreover, at a pound more than the Callender and Leacock maple chests of drawers, Shinn's may have been of a more complex design. Perhaps it was a triple chest like the "walnut Chest of Drawers In - 3 parts and a Little Chest of Drawers," which cost John Rouse a combined £18-0-0, on 10/27/44.434 Triple chests of drawers are an unusual form. One that survives is the cherry triple chest of drawers from the Morris family.435 As Shinns and Morrises intermarried, it is tempting to speculate that the Morris chest may have been the one Shinn ordered.436 The Morris triple chest was given to PMA by Lydia Thompson Morris, but it is not known how it came into her family. It is believed to have been used at Cedar Grove, the home of Elizabeth Coates Paschall.437 The Morris chest of drawers cannot be the Rouse chest, even though each is unusual in being a triple chest, as Head explicitly described the latter as being of walnut.

The "walnut Chest of Drawers In - 3 parts" made for Rouse was also the last piece of furniture recorded in Head's account book. As such, it was fitting that Head had created something special, just as he had done with his first piece of recorded furniture, the "feneared Chest of Drawers," which was ordered by James Poultis in 1718. Because they were his first and last pieces, perhaps he also took the time to record them for posterity with greater particularity.

2. "To a Chest of Drawers and a Table."

The "table" referred to in these paired listings was undoubtedly a chamber table, or what we would now call a dressing table or lowboy.443 This may be deduced from a more descriptive 1725 entry, "To a Chest of Drawers and a Chamber Table,"444 at £9-10-0. That is the identical price found in seven contemporaneous entries, describing the "Chest of Drawers" with just a "Table,"445 and in an eighth entry, "To a Sader Chest of drawers and table of drawers." This last pair was sold to James Steel, whose probate inventory showed a bequest to his widow Martha of "1 Cedar Chest of Drawers...£3-0-0," perhaps from that pair.446 Only three of the £9-10-0 model were of undesignated wood. The rest were described as from woods other than walnut: mahogany, cedar, cherry and maple.

The next most numerous model is that at £10-0-0, of which there are six entries.447 At £10-0-0 and above, all of the entries are for en suite pairs in designated woods other than walnut: three in mahogany, two in cherry and one in cedar. As the £9-10-0 pair was available in those same woods during the same timeframe, it would appear that Head is not charging extra for the type of wood used in the £10-0-0 pair, and that the latter is either larger or more elaborate.448 In any event, among Head's most expensive pairs of "a Chest of Drawers and a Table," customer preference appears to have been for woods other than walnut.

The capabilities of the cabinetmaker who made the Wistar high chest and dressing table, now attributed to John Head's shop, have been assessed in the following words: "[T]he accomplished craftsman who made these pieces was highly skilled in the development of scale and form - an issue in American furniture - undisguised by decorative additions. The elegant proportions...reveal a thorough apprenticeship in the cabinetmaking trade, in a step beyond that of the joiner. The double mold on the case around the drawers is an early detail...outlining as well as protecting the edges of the drawers. A single mold outlines the swinging cusp curves of the skirt on the high chest and dressing table, offering a finished rounded edge which makes a smoother than usual transition between the "flat" case and the turned legs.... The trumpet-turned legs are especially crisp, and the pendants on the dressing table are subtle summaries of the leg form reduced to ornamental appendage. The curves of the flat stretchers on the high chest repeat in the horizontal plane the curves of the case apron, giving the base structure of these pieces a vitality, and visual interest transferred, in later periods, to the urns, flames, and scrolls on bonnets and pediments."449

The Wistar high chest and dressing table probably embody the basic "look" of the en suite pairs produced by the Head shop, as fifteen of the at least twenty-six pairs recorded were made in 1723-1726, contemporaneous with the Wistar order. No one was recorded as having supplied Head with turned frames. Head was undoubtedly turning such frames in-house. Thus, he supplied James Lippincot a "payer [of chests] apon a frame" and charged Joseph Chatam [Chatham] "to turning five ledges [legs] for a Chest of drawers."450 That Delaware Valley dressing tables with turned legs and intersecting flat stretchers were being made as late as 1724 is corroborated by a walnut one bearing that date inlaid on its top.451

That fifteen of Head's twenty-six pairs of chests of drawers and dressing tables were ordered during 1723-26 may be no coincidence.452 This surge in sales may have been the result of sudden increased prosperity for some of Head's customers, brought about by the issuance of paper currency in 1723 and 1726.

At some point, however, Head must have dispensed with the inherently unstable construction of tenoned legs in favor of mortised cabriole legs. After all, well past the introduction of the cabriole leg, Head continued to record the making of dressing tables (until 1737) and chests of drawers (until 1744). Even if not an innovator, such change had to have been made just to remain competitive. Regrettably, unlike the "crook'd foot" of the Fussell ledger, the Head account book does not use any terms that expressly fix when the cabriole leg was first adopted.

|

Fig. 26: Dressing table on cabriole legs with ankleted Spanish feet, between two chairs from Joseph Richardson

Fig. 26a: detail of Persian arched skirt, pendants, and double-moulds around drawers Fig. 26b: detail of four forward-facing carbiole legs on ankleted Spanish feet, dovetailing of case, and double-arched skirt with pendant Private collection, Philadelphia

|

|

Fig. 27: Dressing table on cabriole legs with squared feet and incised bead on skirt

Private collection

Photograph courtesy H. L. Chalfant Antiques |

A closely related, but slightly later, dressing table on cabriole legs with squared feet, perhaps from the same shop, exhibits the next stages in development of the form [fig. 27].457 Its drawers are no longer flush with the front of the case and surrounded by mouldings, but lipped and overlapping the drawer holes. In place of the applied bead on the skirt is an incised line. The Persian arches and the pendants separating them have been eliminated. But the unmortised fastening of the legs into the corners of the dove-tailed case remains the same.

|

Fig. 28: Dressing tables on cabriole legs with Spanish feet.

Right: from Smith family of Burlington, N.J., with incised bead on skirt and stamped brasses. Private Collection. Left: with protuberances in place of pendants Fig. 28a: Detail of construction, side skirt profiles, legs and knee blocking. Mones Collection |

A stockinged trifid-foot, curled maple dressing table, which sold at Christie's in 1999, has a similar skirt design to that on the Mones table, but in place of a top tier of three drawers, has a single drawer with three lipped-facings, giving the appearance of three separate drawers.461 Another with the same skirt and three-in-one top drawer design has fluted chamfered corners and an incised bead along its skirt edge.462 The Spanish-foot walnut dressing table at HSP, also part of this group, has a trefoil at the top of its skirt, as well as the incised bead. According to Rick Mones, it is the mate to a high chest of drawers at Stenton.463 The pair descended from Deborah Norris Logan, daughter of merchant Charles Norris (1712-1766). Related high chests of drawers include a Spanish-foot walnut one in the Mones collection with the trefoil and the incised bead on its skirt, and its original stamped brasses [fig. 18]. An examination of the design and construction details of this entire group is required in order to determine the extent of their interrelationship, and whether they emanated from one or more shops, including that of John Head. Any protuberant substitutes for the pendants were eventually to disappear altogether, as skirt design became ever more undulating and developed entirely new rhythms [fig. 1].

Demonstrating how difficult it is to chart stylistic changes in furniture is the December 19, 1741, four pence charge in the Fussell Ledger to "an ornament Ball for a Dressing Table."464 This should not be interpreted as a skirt pendant or as a finial atop the intersection of flat stretchers. By this time, such designs were out of fashion. Head did not record receiving any such "ornament Balls." His closest entry is for the "Balls : dd [delivered]: by John Rutor [Rutter?]," debited to the account of "Thomas Williams, plasterer." Thus, they were probably not even for use on furniture.465

The least expensive chamber table, at £1-6-0, was debited to William Clar [Clare], on 6/30/29; the most expensive were the three, at £2-5-0 a piece, debited to Samuel Hudson on 1/3/21, to Simond Hagal [Simon Edgell] on 6/30/29, and to Thomas Radman on 10/28/30.468 In between those price points, two other chamber tables were individually debited at £1-10-0 and £1-12-6.469 But Head's most popular and consistently priced model was that at £1-15-0, of which twenty-seven were sold between 2/12/21 and 1/24/30.470

In 1723, the £1-15-0 chamber tables started to be separately debited either on the same date as, or in close proximity to, the likewise popular £5-10-0 chests of drawers471 -- apparently as companion pieces -- and in one instance, one was paired with a £5-15-0 chest of drawers.472 This coincidental dating of separately debited chests of drawers and chamber tables continues until 1729.473 It is thus contemporaneous with Head's most prolific period for the combined entries, "To a Chest of Drawers and a Table," and may be further evidence of the prosperity engendered by the currency acts of 1723 and 1726. Indeed, these separately debited "pairs" are priced, in the aggregate at £7-5-0 or £7-10-0, the same as several of the combined entries during the same period.474 This suggests that they were all like models of chests of drawers and chamber tables, and of en suite design, even though separately debited.475

4. "To an oval Table."

The least expensive oval table was a £0-18-0 "pine" one ordered by Thomas Shinn.478 Next in price was Thomas Canby's £1-5-0 otherwise undescribed oval table.479 Both of these may have been diminutive in diameter, as a "Smal" oval table cost only £1-15-0. Tables of similar dimension may also have been used in pairs, as two oval tables were purchased at double that price by Matthias Aspdin.480

It is open to debate whether the least expensive, undesignated oval tables were of pine or of walnut. Eleven of them were priced at £1-10-0, of which only one, that ordered by Edmond [Edmund] Woolley, had its wood designated: "pin."481 On the same date as his £0-18-0 pine oval table, Shinn also ordered a walnut one at £2-10-0.482 The only other oval table for which a wood was described was Thomas Masters's "mehogany oval table som stuf & Joynts & draps & Glew" [joint hinges & drop pulls & glue], at a combined price of only £1-18-0. 483 Thus, it was entirely possible that Head's £1-10-0 oval tables included not just Woolley's pine one, but some of other woods, as well. Tables not of pine may have been smaller in size, reflecting the greater expense of the wood chosen.

The most popular model of oval table cost £2-5-0. Fifteen were ordered.484 In addition to the Shinn walnut one, two other oval tables at £2-10-0 were recorded. One of them was expressly noted as "with two Loks."485 This would indicate that this table must have had two drawers, presumably back-to-back under the mid-section. Perhaps the popular £2-5-0 model, therefore, had only one drawer or none. Certainly the least expensive oval tables would not have had drawers and might not even have had the two drop leaves suggested by the "Joynts" for the mahogany oval table.

Oval tables described as "Larg" included ones at £2-5-0, £2-11-6, and £2-12-6.486 An "oval Table: 4 foot 1/2" cost £2-12-26.487 The most expensive oval tables, obviously popular, were those ordered, at £3-0-0, in six different accounts.488 The £3-0-0 tables were probably the same size as the one at that price debited to Thomas Hill, that was specified as an "oval Table : 5 fot Bad [5-foot board]."489 The largest oval table documented as made in this period was the seven by eight foot one ordered, in 1725, for the Chester County Grand Jury Room from John Owen (d. 1752).490

Head's account book does not expressly state that his oval tables were on frames. However, Head charged Joseph Chatam £0-4-0, "to turning a table frame."491 Also, many surviving examples of oval tables from Head's period, in the same sizes as made by Head, attest to their popularity.492 Further confirming that oval tables on frame were contemporaneous with many of Head's own oval tables is one inlaid "1725 IEB," for James and Elizabeth Bartram.493 That oval tables had frames may be supported from another documentary source. In 1729, Thomas Shute consigned to Thomas Chalkley (1675-1741) for sale in Barbadoes, "One Oval Table & Frame," at £6-10-0.494 As with the high chests and dressing tables, there probably came a point when Head switched his tables to cabriole legs, but his account book does not tell us.

5. "To a squar walnut Table."

|

| Fig. 29: tray top tea table with scalloped skirt on cabriole legs with pad feet

Private collection Photo courtesy H.L. Chalfant Antiques |

6. "To a Stand for a Candle"

7. "To a Table."

At least seven of Head's tables, perhaps including his oval ones, were turned by Alexander Foreman, one of his chair suppliers.508 It is conceivable that the "Tee table," for which Head charged Steel £1-7-0 on 1/9/26 was the "Round Tea Table" listed in Steel's inventory.509

Head also produced "a frame for a slat [slate] Table," for James Steel, charging him £0-15-0. Two other customers appear to have gotten frames for slate-topped tables from Head. Edwd [Edward] Horn was debited £0-18-0, "To a frame for a Slate;" and Boulah Coates £0-16-0, "To a fram[e] for a slat[e] & a pine Tope for an ould frame."510 Pieces of "black slate" were plentiful in "some parts of the Skullkill," and were "four feet and above square." Their color and configuration was the same as "Table slate."511

8. "To a Chest."

Not to be confused with Head's most popular seller, the "Chest of Drawers," was his simple "Chest." The wood choice for the latter was of the commoner sort, usually of pine or cedar. Of the fourteen debited, ten chests were described as being of "pine" or "pin," two of "Sader," and two were undesignated.513 Head's chests probably shared some of the same features. As he had purchased at least twenty pair of butt hinges,514 and 5 dozen till locks,515 and considering unascribed surviving examples of that period, the chests were probably dovetailed boxes on feet (or in the cheaper price ranges, without), surmounted by a lid, hinged in back and lockable in front. There may or may not have been a till inside.

The most common model of chest was that at £0-14-0, of which 6 were noted, all of pine. It probably was drawer-less, as the only chest listed with drawers, a "pin chest with 2 drawers," cost Cristofar Topam [Christopher Topham?] significantly more, £1-5-0, on 6/5/20.516 That was also the earliest chest recorded.

The latest chest was "dd [delivered] to Elizabeth Whals [or Whaly?],"on 4/23/36, and was charged to John Coster, at £0-6-0.517 As no wood is designated, and this is the cheapest chest recorded, it must have been of pine, like the other less expensive ones, and quite small.518 Head had previously obtained "on[e] dosen small Buts [butt hinges]," which he may have used to secure the lid of just such a chest.519

A "Larg pine Chest" cost Jon [Jonathan?] Lade £1-0-0 on 6/9/26.520 The most expensive chest recorded is the "Sader" one, for which Artha [Arthur] Jones paid £2-0-0 on 8/4/27.521 While another entry, "To maken a Sader Chest som my stuff," clearly establishes that Head's shop was making these simpler chests and not serving as a middleman, its price, £1-5-0, is probably less because Head was apparently supplying only part of the "stuf[f]" from which it was made.522 What is surprising, is that Head, in "1728," credited £2-0-0 to the account of George Cosins [Cousins?], "By an ould Sader Chest," the same price he was getting for a new one. Perhaps there was something special, albeit unstated, about the chest taken in. Alternatively, as cedar was used as a prophylactic against infestation of garments and fabrics, maybe the chest could still be resold at £2-0-0, as Head's customers were more interested in its use than its appearance.523

9. "To a Badstad."

Head's earliest debit entry for a bedstead was that on 9/13/20, to the account of Thomas Masters. It is also his most expensive single entry including a bedstead. At a cost of £2-0-0, it was described as "To maken a badstad & Cornish [cornice] & fotpost." Although no wood was identified, it is conceivable that it was made of "mehogany," the wood specified for the cradle and oval table, which Masters also ordered from Head that year. This may, in part, account for the additional expense. Head's latest bedstead was debited on 11/26/36 at £1-0-0 to John Coster and "dd to Mikel Hilliges [Michael Hillegas].528

The Masters entry also leaves no doubt that Head's shop was "maken" bedsteads. Another debit entry shows Head turning bed posts.529 An examination of the credit side of the ledger, however, shows that Head was not always making his bedsteads from scratch. Most of the time, Head was supplied by others with substantial numbers of "badstads."530 As these were credited at a fraction of the price at which Head was selling his bedsteads, they were probably unfinished components, such as bed posts or frames. Thus, Head credited John Hains £2-0-0 on 9/19/20 "To - 10 : badstads." That was the same price Head had gotten "To maken a badstad & Cornish & fotpost" for Thomas Masters the prior week on 9/13/20."531 It would then have been up to Head to do any additional turning, planing, pegging or finishing. On at least one occasion, however, he clearly got someone else to turn bed posts.532

Head nowhere specifies the wood from which his bedsteads were made. Many may have been of red cedar, the preferred wood for bed enclosures, posts, and the horizontal planking supporting the mattress. In its absence, white or black oak was commonly used. Head credited his neighbor, house carpenter Edward Worner [Warner], £0-0-6 on 7/9/35 "By a Bad post," which may have been cedar. On the same date, he credited Warner £0-4-11 "By - 59 foot of Sader bords;" and on 2/17/34 £0-0-1 "By a sader post." Head may have also made beds from maple, a wood used for "feet [legs?] for chairs and beds."533

Head's least expensive bedsteads were priced at £0-14-0. They were also among his most popular. Nine were sold as early as 11/9/22 and as late as 5/26/35, to a diverse group of customers, two of whom Head helps to further identify for us: John Williams, "the Tailer," and Jno [Jonathan] Fisher, "ye Shoumaker."534

By far the most popular model was that at £1-4-0, of which thirty-four were ordered.535 Head charged £1-9-0 "To a Badstad and painting of it."536 Even more expensive was the 7/9/22 order to brickmaker Abram Cox, which was broken down into several entries, and provides the clearest indication of the appearance of a Head bedstead: "To a Badstad £1-4-0/To 2 posts Blakit And varnishit ["blackened and varnished] £0-4-0/To a Cornish Blakit & varnishit £0-10-0/To Comperst Rods £0-16-0/To 8 hoks & 2 scrues £0-2-6."537 The "Comperst Rods" refer to a tester that was compassed, or arched, as in a "compass roof."538 Cox is recorded as having had a "Canopy Bedsted," perhaps this one.539 The "scrues" probably refer to bed bolts.540

There is the intriguing possibility that Abram Cox's "Blakit & varnishit" bedstead may have been "Japanned," and meant to go en suite with the "1 large Japand Looking Glass" he is recorded as having in 1735.541 "Japanning" was a process whereby less expensive woods were painted (usually with lampblack) and varnished to emulate Oriental lacquer work. Boston and New York have previously been recognized as major centers for such work in this country, long popular in England.542 Japanned furniture had been advertised and probated in 18th century Philadelphia.543 But, the lack of surviving Philadelphia examples has impeded knowledge of how such pieces were made, and whether they were made here or solely imported.544 A contemporary Philadelphia newspaper reveals that a "Mrs. Dickson, from Scotland," proposed "to teach young Ladies to...Japan upon Glass or Wood, and Varnishing...," but nothing per se shows that furniture was being Japanned in Philadelphia.545 Head's "Blakit And varnishit" bedstead may evidence Japanned furniture being made in Philadelphia. If that entry was meant to refer to Japanning, it would also be the earliest to document the names of a Philadelphia cabinetmaker and original owner of Japanned furniture, and the order date and price.546

Head also sold other items required for beds. Head charged John Burr £3-0-0, "To - 30 pound of f[e]athers." "Sacken bottom[s]" were sold, at £1-2-0 a piece, to William Chanceler [Chancellor], who took two; and to John Campbell.547 Head sold "60 bad pags [pegs]," at £0-2-6, to Joseph Cooper Junor [Jr.], and another set at the same price to Benjamin Clark.548 On 9/21/19, the earliest entry in the account book concerning beds, Head charged Paul Preston £0-2-0, "To a Sat of Bad Larth," probably lath cross-pieces.549 James Steel apparently needed not just the lath, but the erection of the bedstead, as he was debited £0-2-6 on 9/21/32 "To Bad Larth and puten his Badstad up." Thomas Canan required even more help. He was debited £0-3-6 on 9/11/31 "To taken his badstead Down & puten it up & Curten rods & had & git Bords." "[H]ad" may refer to a headboard, as Head usually referred to the cornice as a "Cornish."550

Head also sold, or acquired for his own use, what was elsewhere commonly referred to as bed "furniture" from others.551 On 6/11/25, Head credited John Roberds £0-10-0 "To a Sate [set] of Curtion [curtain] Rods." On 2/1/27, he debited Joseph Endecot [Endicott?] for £0-8-8 "In Badstad Stuf By James Lippincot," previously identified as a supplier of bedsteads to Head. Head credited £4-5-0 to the account of Peter Cloak, on 10/20/43, "By a sut [set or suite] of Curtens and five yards of Linen."552 Others received credits in varying amounts for other fabrics suitable for curtains, including "muselen," or muslin, with which beds could be draped in summer, as a protection against mosquito and gnat bites.553 Kalm's description of his encounters with Philadelphia's airborne insect population makes for amusing reading.554

10. "To a Clock Case"

a. Clockcases.

|

Fig. 30: Arched face clockcase with Peter Stretch clock and brass-framed oculus

Fig 30a.: Detail of hood, dial, and blind fretwork Mones Collection

|

The next most popular model, of which thirty-one were debited, was priced at £4-0-0. These may all have been for arched dial clocks, as six at that price were described as arched, dating between 1721-1727, including a 1726 entry to Peter Stretch.558 These also provide the earliest documented dates for the use of American arch dial clocks.559

The description of the earliest of Head's £4-0-0 entries, that to Richard Harrison on 7/16/21, is especially intriguing.560 "To a Clockcas Archit plat" appears to refer to something more than a case for an arched top clock. The "plat" may allude to a either a "platform," i.e. a flat surface used in support of something above it. More likely it refers to a "plateau," a term once used to refer to "a removeable and usu[ally] decorated top," as an inlaid or marble top for a table.561 This may be a reference to what would today be called a "sarcophagus-top" in America or a "caddy-top" in Great Britain, one with alternating flat-vertical and ogee steps [figs. 5, 5a, 30, 30a]. Normally surmounted by finials, some also had something akin to a coxcomb atop their center. In many instances these tops simply sat on the clock hood, without being permanently secured. The ability to remove them was no doubt in order to accommodate ceiling heights during set-up, or to manipulate a tall clockcase within the bounds of the narrow staircases of Philadelphia's early houses.

Head's "Archit plat" was apparently not a pedimented or ogee top, as these terms were used contemporaneously to mean something different than arched. Josiah Claypoole, "from Philadelphia," advertised "Desk and Book Cases, with Arch'd, Pediment and O.G. Heads."562 Head also used the term "head" with respect to clocks, spelling it phonetically as "had." On 3/27/32, Peter Stretch was debited £1-0-0, "To a had for a Clock."563 Head may have been using "had" to describe something above the hood, such as a "plat," the hood, or both.564 There was no such confusion when Head charged Richard Harrison £0-3-0 on 4/29/22 "To a had for a Looking Glas & mending bak." A simpler form, the looking glass was getting what today would be called a new "crest."

An "Archit plat" or a "had for a Clock" might also have had "freezes [friezes]," now referred to as blind fretwork. On 4/28/42, Head debited Thomas Maul [Maule] £0-3-0 "To - 2 Clock Cas freezes;" and on 4/21/43 (£0-1-6) "To a Clock Cas frees."565 In 1755, a year after Head's death, Thomas Maule advertised "clock-case freezes" for sale.566 The hoods of Head's clocks were also decorated with columns, as is evident from his charge of £0-1-0 to turner Alexander Forman [Foreman], on 8/14/26, "To dameg To ye Clockcas pilers."567 Blind fretwork and pillars are found on a Peter Stretch clock in a walnut case [figs. 30, 30a].

All of the cases from designated woods other than walnut were priced at £5-0-0, and were the most expensive Head sold.568 Four were of cedar, all dating from the early 1720s.569 Cedar would thus appear to have been the most popular of the designated woods among Head's earliest clockcases. Perhaps demonstrative of a change in taste, the three of mahogany date from the mid- to late 1720s and, despite being made of imported wood, were priced no differently than the cedar or cherry cases.570 The four of cherry all date from the 1730s, with one exception from 1723.571 One clockcase, sold to Peter Stretch, was described as "Blak."572 Japanned pieces were painted on less expensive wood, but this case was priced at only £2-0-0.573 Therefore, it is open to question whether it was Japanned, or merely painted black with no additional decoration.574

The least expensive clockcase appears to have been one priced at £2-5-0, together with a table.575 Given the relatively modest combined price, this 1738 entry may refer to a case for a bracket clock, sold with an accompanying table on which to display it.576 A year earlier, on 4/7/37, Head had given Peter Stretch £2-10-0 in credit for what was probably a second-hand bracket clock, "A Little ould Clock.577 According to Hornor, in 1742, Philadelphia sailmaker William Chancellor had "One Table Clock" in his "Parlour."578 "A Small Spring Clock £1-10-0" was owned by joiner Joseph Claypoole in 1744.579

b. Glazing Clockcases.

That some clockcases were sold without glazing may have been a precaution against breakage, particularly for those that had to be shipped longer distances or were to be exported. As an extra precaution, at least one glazed clockcase was shipped within a packing case. The "Clock cas and Glasen," debited to John Leacock, at £3-6-0, on 3/14/36, was accompanied by a charge of £0-8-0, on the same date, "To a paken Case." Four other clockcases, not specifically designated as glazed, also had packing cases charged for them.584

c. Clockmakers Doing Business with Head.

[1]. "John Hood Clock maker."

The only John Hood appearing in the Will Books of the Philadelphia Register of Wills during the period of Head's residency is "John Hood of Darby," who died in 1721, too early for the Hood transactions in Head's account book. While his son of the same name is noted as deceased, one of his heirs was his grandson of the same name. However, no indication is given in the will as to the profession of any of them.590 The next will proved for a John Hood does not occur until 1775, a date which may be too late for Head's clockmaker. His bequests do not confirm him as a clockmaker. He left a "silver watch" to a brother in Ireland; and, to Thomas Paul, his "Turning Lathe & Turning Tools such as Gouges & Chesils."591 The latter suggests he may have been a turner of wood rather than metal clock parts.592

Head did business with clockmaker John Hood from at least 1740, when Head delivered to Hood the clockcase charged to Cresson.593 Just before the debiting of the other clockcase on 7/29/43, Hood's account was credited £3-10-0, on 7/14/43 "By a Laram [Alarm] Clock,"594 which Head simultaneously debited in the same amount to Thomas Brown.595 These entries provide a firm date by which alarm clocks became available for sale in Philadelphia.596 In their last recorded transaction, on 12/4/48, Head credited Hood's account £0-7-6, "By Cleanen a Clock."597

John Head provides another clue as to the personal life of John Hood. In the account of Mary Snad Junor [Mary Sneed, the Younger], he notes "1730 new wife of John Wood." Here Head did confuse Wood with Hood. "A Lot of Ground situate in High Street, adjoining to David Evans's, belonging to Mary Sneed, deceased" was later advertised for sale, noting that inquiries could be directed to "John Hood, living in said House."598 It would thus appear that Mary had been married to John Hood, not John Wood. The advertisement would also suggest that Hood conducted his business from their High [Market] Street residence, as that was the most commercially used street in Philadelphia.

[2]. John Wood, Sr.

|

|

Fig. 31: Arched face clockcase with John Wood, Sr., clock

Fig 31a.: Detail of hood and dial Mones Collection |

Fig. 32: Arched face clockcase with John Wood, Sr., clock

Fig 32a.: Detail of dial Private Collection, Philadelphia |

[3]. The Richardsons.

There are no references in the Head account book directly linking Head's shop with either the case for the Francis Richardson, Sr. clock, or with an "Arch Moon Clock and case," for which Joseph Richardson, Sr., debited his uncle Lawrence Growdon £19-0-0, on August 25, 1732.608 However, there is no question, that Head did business with at least one member of the Richardson clan. Francis Richardson, Jr., son of Francis Richardson, Sr. and brother to Joseph Richardson, Sr., had an account with Head.609 "Frances Richerson" was debited £4-0-0, on 8/13/36, and £3-0-0, on 9/25/36, on each occasion "To a Clockcase dd to himself."610 That year and the next, Francis Richardson, Jr. advertised as a maker, cleaner and repairer of clocks.611

[4]. The Stretches.

In the course of restoring and authenticating many early Philadelphia clockcases in the last twenty years, conservator Christopher Storb recognized that approximately seventeen of them bore construction and design details linking them to a single cabinetshop. Most of the group housed movements labeled "Peter Stretch" and, in some instances, "William Stretch" and "John Wood." However he had no way of identifying which of Philadelphia's cabinetshops had made the cases. The several dozen entries in the John Head account book to clockcases for Peter Stretch, William Stretch, and John Wood have now enabled Storb to establish a basis for attributing cases in the group to the Head shop.614 One Peter Stretch clock, with one of his "top-of-the-line" tide dial movements, is in a walnut case with a cyma-curved base characteristic of Head [figs. 5, 5a, 5b, 5c]. The case is thought to be by Head's shop.615

Some forty-one clockcases in the Head account book were debited to the account of clockmaker Peter Stretch.616 Of these, the least expensive, at £2-0-0, was recorded, on 5/1/32, as "Blak," presumably a reference to a less expensive wood either painted black or Japanned.617 This also provides some idea of what may have been paid for the "Square faced black Case & Clock" in Hannah Cox's home in 1747, cited by Hornor.618 Head's next least expensive clockcase to Stretch was charged at £2-15-0, without further description.619 Twenty-two were debited at £3-0-0, one of which was identified as "Walnut" and two as "Squar Case."620 Another fifteen cases were at £4-0-0, of which two were "Arched."621 Only two cases were priced any higher, at £5-0-0, both in cherry.622 No other woods were noted as being used for clockcases debited to Peter Stretch.623 The same is true for the two cases shown as debited or delivered to others on the same dates as clocks delivered by Peter Stretch. Both of these were debited at £5-0-0, to the account of John Leacock, together with £15-0-0 clocks by Stretch. One was on 3/31/34; and the other was on 8/25/34, "dd [delivered] to William Calender [Callender]."624 This latter clockcase also may have been of cherry, as the 1763 inventory of Callender's estate listed "an Eight Day Clock with Cherry Tree Case" in the "Front Parlour."625 If this was the same clock and case as in the Head account book, it also confirms that Stretch's £15-0-0 clocks had eight-day movements, as would be expected, given their high price.

The earliest case debited to Stretch was the "Walnut" £3-0-0 model on 5/3/24.626 The latest, on 2/23/42, was also at £3-0-0.627 The £4-0-0 cases were produced simultaneously, the earliest being the "Arched" one debited 2/26/26, and the latest recorded on 4/22/41.628 As previously stated, the £5-0-0 cases were both debited in 1734.

Peter Stretch was also recorded by Head as delivering two clocks debited to other accounts, neither of which references clockcases. These individuals must have already had cases or were getting them from other sources.629 The first, a "1726" debit of £11-10-0, to Joseph Taylor Junor [Jr.], "To Clock Work de:d by Peter Stretch," was obviously meant to settle up a huge credit which Taylor had in Head's book, "To a parsel of Chary Tree Bords and Logs," on 8/24/25.630 Head had apparently paid half down, as debits to Taylor's account, on the same date, show a total of £11-10-0.631 The remaining half was thus made up by Stretch's delivery of the "Clock Work." The only other clock delivered by Peter Stretch without a case to a Head customer was debited to the account of John Guest, in the amount of £6-0-0, on 3/16/38.632 These entries demonstrate how the interrelationship of Head's and Stretch's businesses facilitated the operation of the barter system on which they were both dependent.

Peter Stretch's account, apart from clockcases, was also debited for many other items, including furniture,633 and the mending of it.634 Between 1/22/22 and 3/13/25, Stretch was charged for twenty-five "Scal[e] Box[es]," one of them "Larg."635 These may have been the type of box to hold scales and weights for the weighing of precious metal, advertised by Philadelphia silversmiths.636 Scale boxes with labels of Philadelphia silversmiths and merchants survive. The labels bear the values of coinage at that time. Most of these scale boxes are of oak and otherwise identical to those with English labels.637 One, however, which descended in the Stretch family, is of walnut [fig. 9]. It bears two labels, both of Philadelphians. The label of silversmith Joseph Richardson is superimposed over that of merchant Joseph Trotter, presumably because the value of the coinage had fluctuated in the interim.

One of the most informative debit entries in Peter Stretch's account is "To mending a pine Table and Three round peeses to Cast By," at £0-5-0, on 10/18/39.638 This confirms, what had been previously only been suggested by his inventory, namely that Stretch cast at least some of his own clock parts.639 Head does not disclose what wood he used for those "peeses," but Kalm recorded the following regarding moulds made from Liquidambar Styraciflua or Sweet Gum-tree: "Mr. Lewis Evans told me, from his own experience, that no wood in this country was more fit for making moulds for casting brass in than this."640

Peter Stretch often paid his account to Head in clocks. His account was credited for several clocks, four of which were described as "ould."641 Among nine new clocks credited to Stretch, four were identified in debit entries of Head's customers as being delivered (and thus presumably made) by Stretch, on the same dates and at the same prices as credited to him. These were the two £15-0-0 clocks to William Calender [Callender] and John Leacock, both charged to the latter;642 the £13-0-0 clock debited to Jonathan Miflen [Mifflin];643 and the £6-0-0 clock debited to John Guest.644 But without the £13-0-0 credit, on 3/2/39, for a clock "dd [delivered] to Benjamin Lee," one would not have known that this clock, too, involved Peter Stretch, as the simultaneous debit entry to Lee's account, in the same amount, made no mention of him.645 The £13-0-0 clocks to Miflen and Lee were probably eight-day "Arch face" clocks, like the one appraised for that amount in Stretch's probate inventory.646

Credit entries to Peter Stretch's account also enable a Stretch attribution and identification of component prices for two transactions debited in the aggregate "To a Clock and Case." Neither debit entry had broken out the prices of the clock or case, or mentioned Stretch. Thus, as Stretch was credited £12-0-0 "By a Clock" on 6/29/32, and on that same date James Steel was debited £15-0-0, it is not only clear that Steel got a Stretch clock, but that its case cost £3-0-0.647 The same is true for an otherwise identical transaction to John Hains [Haines], on 9/28/41.648 At £3-0-0, these were probably "Squar Case[s]." At £12-0-0, the clocks were likely Stretch's square face, eight-day clocks. The inventory of Peter Stretch's estate included an "Eight day Clock Square face," at £12-0-0, and another, with a "Case," at £15-0-0.649

As four of the clocks Head credited to the account of Peter Stretch were described as "ould," not all of the credited clocks may have been originally made by Stretch.650 None of these old clocks show as being debited to any of Head's other customers on the same dates or at the same amounts. It is possible, however, that Head sold them in combination with certain of his clockcases that he debited jointly in a single transaction. Thus, it would appear that the "ould Clock" that Head got from Stretch, on 8/4/33, at £4-10-0, was the "Clock" component of the "Clock and Case," that he debited to Thomas Fitswarter [Fitzwater] the next week [8/10/33], at £7-10-0, presumably in one of his "Squar" cases.651 Likewise, the £3-10-0 credited Stretch for another "ould Clock", in 5/37, was probably part of the "Clock and Case," that Head charged Thomas Carrall [Carroll?], on 5/14/37, at £7-10-0, presumably in one of his arched cases.652 This would also explain why the £7-10-0 clocks and clockcases are cheaper than what Head had been charging for new clocks and clockcases aggregated in single entries.

Other credits to Peter Stretch's account with Head are what one would expect of a clockmaker. Stretch twice supplied Head with clockcase hinges.653 Other credits were for cleaning and repair. Stretch was credited £0-12-0, "By Cleaning 8 day Clock" [12/14/36]; £0-5-0, "By Cleaning an old Clock and top for pendelun" [1/37]; £0-11-0, "By Clening and mending a Clock" [4/28/37]; and £0-7-6, "By Cleaning a Clock" [11/23/37]654

Other than the few clocks that survive him, little has been known about William Stretch (d. 1748), Peter's son.655 One clock by William Stretch, in a walnut square dial case, has been attributed to Head's shop [figs. 6. 6a]. Mones Collection.656 After Peter's demise, in 1746, William succeeded to his father's business, his brother, Thomas, having already been separately established.657 Head sold four clockcases to William Stretch, each at £3-0-0. The first was in 1727, and the rest in 1730.658 The price of these cases infers that William Stretch was making square face clocks for what were apparently "Squar Cases," although not so described. William Stretch had previously been credited for providing two "payer Clock Cas Joynts [joint hinges]," at £0-3-6 each pair, and a "clock" at £13-0-0.659 The £13-0-0 clock may have been an eight-day "Arch face" clock, like the one appraised in that amount in his father Peter's estate.660 Final settlement of William's account, on 11/29/30, included £1-4-0, "By Cash paid by his Father."661

No mention is made in Head's account book of Peter Stretch's other son, Thomas Stretch (d. 1765).662 Thomas is best known "for making the State-house clock."663 Thomas was also the first "governor" of the "Colony in Schuylkill," a fishing club founded in 1732, whose charter members included Head clientele James Logan, John Leacock, and coroner Caleb Cash.664

Samuel Stretch (d. 1732), a nephew of Peter, also worked in the family business. The one mention of him in John Head's account book was a posthumous one. His uncle Peter's account was debited £2-10-0, "To Samuel Stretches Cofin," on 1/30/32.665 This shows that Samuel survived less than a month, after making his will on March 7, 1732.666

11. "To a Dask;" "To a scrudore and Bookcas apon a Chest of drawers."

While no further description is supplied regarding any of the above desks, some of them may have been on frames. William Robens [Robins], was debited £0-7-6 by Head, on 2/17/24, "To a Dask fram," and then £0-15-0, a day later, "To a Writen Table."675 Robins, as a teacher of "WRITING, Arithmetick, Book Keeping and the Mathematicks," may have had need of the table for his students.676 Head also gave ship carpenter and fabric importer Thomas Wells a credit of £1-7-6, "By an ould desk apon a frame," on 11/26/31. The description is perhaps an indication that, by this point in time, a desk-on-frame was a form passé.677

Head made two bookcases and mended another, but there is no indication in any of those accounts that they were meant to go atop desks.678 However, the account of James Steel does list bookcases in combination with desks. On 2/7/36, Head debited Steel £14-0-0, "Left to pay for a Desk and Book Case and - 2 paken Cases By his order was sent to marriland [Maryland]."679 On 7/3/36, Head also debited Steel £15-0-0, "To a scrudore and Bookcas [secretary desk and bookcase] apon a Chest of drawers."680 One of these was probably the "Desk & Book Case w[i]th Glass Doors," valued at £15-0-0 in Steel's probate inventory.681

12. "To a Cradle."

Thomas Masters (c. 1684-1724) had been born in Bermuda. He held many governmental posts, both on a municipal and provincial level, serving two terms as Philadelphia's mayor, and also on the Provincial Council. He became one of its most prosperous citizens. Masters was a Quaker, whose meeting attendance, at least from 1707-1717, was described as "extremely active."686 Whatever the degree of his religious devotion, it does not appear to have conflicted with Masters's taste for mahogany. Apart from the cradle, Masters also ordered a "mahogany oval table."687 The cradle and oval table were the only mahogany examples of those forms recorded by Head. Mahogany was a wood seldom ordered by Head's largely Quaker clientele, perhaps because it generally was more expensive, or because it had a more extravagant look than walnut.688 Masters's death, on January 11, 1724, occasioned the settling of his account with Head by his son William, in the amount, on 3/5/24, "To Cash paid by His son William After His Dath."689

13. "To a Corner Coberd."

14. "To a Clos Stol."

15. "To a Close Pras"

16. Boxes and Cases

Another relatively expensive container made by Head was the "Raser Case of mehoganey," that he debited to George Cunningham, on 3/6/24, at £1-5-0. As Cunningham shaved Head, perhaps Head had the pleasure of seeing his handiwork whenever the razor was removed for use.701

Head also sold a variety of boxes and cases for utilitarian purposes that were priced much cheaper: "To a Wige Box" [George Roach, 8/23/30, £0-2-0]; "To a [k]nife Box" [Hinery Clifton, 5/21/24, £0-2-0]; "To - 12 Candle Boxes" [chandler Thomas Canan, 8/13/31, £0-15-0]; "To a pine Case of Drawers" [clockmaker William Stretch, 7/16/25, £1-2-0], possibly for specialized use within his trade. There is no question that Head's shop made its own boxes, as he charged James Steel "To maken a Box" [8/11/27, £0-3-0]. On occasion, he even remade them. Steel was charged "To maken 2 Boxes of one" [5/9/28, £0-0-8].702 "Paken" boxes and cases were made to protect shipment of clockcases, clocks, other furniture, and a "marvel [he]arth" for Steel.703

17. "To a Trof"

A "Candle Trof" was charged to Alexander Wooddrop at £0-7-0, on 2/7/22. A "banch to Sat a candletrof on," which cost John Mocombs Junor [McComb, Jr.] £0-4-0 on 2/25/21, appears to describe a bench on which to set a trough for dipping candles, as on that same date, McComb was also charged £0-5-0 "To 25 Candle Rods."705

18. "To a Mould"

19. "To a Tray;" "To a Qwilting frame & Trusels.

20. "To a Cofin"

At least seventy-three coffins were sold by Head. All were obviously debit entries with no returns to be credited - a good business. The earliest coffin was billed to Thomas Shut [Shute], on 10/6/18, at £2-0-0, "To a Cofin for his Son."710 The latest, on 11/24/40, at £1-10-0, to Benjamin Mason, was "To his Daughters Cofin."711 Mason's wife's coffin had been ordered only a week earlier.712 She had probably not died in the childbirth of this daughter, as the cost of the daughter's coffin was considerably more than the six or seven shillings which Head charged for the youngest occupants of his coffins.713

The greatest expense for a "Child's Cofin," was the £1-7-0 charged William Coats, "To a Walnut Cofin for his Child," on 3/3/31.714 We know that at least twenty of Head's coffins were for children.715 That so many children's coffins followed closely the ordering of cradles, is a poignant reminder that death in early Philadelphia was no respecter of age. Cristhofer [Cristopher] Thompson's "Dafter" and "Son" died in the same month.716 Pewterer Simon Edgell was particularly hard hit, ordering coffins for three of his children within five years.717 Infant mortality, particularly for those among the lower economic strata, would remain high into the 19th century.718

William Coats, Head's best customer for coffins, appears to have experienced a personal calamity to rival Job's. After purchasing a coffin for his servant on 9/15/27, in the next five years Coats bought five coffins for members of his family: his mother, two children, his "dafter," and, finally, on 11/3/32, for his "wive."cdlx719 These were his only purchases from Head.720

The only set of entries regarding coffins that provides a bit of levity are those concerning the account of James Way. On 6/21/28, he was debited £2-5-0, "To his Wives Redged Cofin," a handsome sum for Head's most elaborate model - obviously for a beloved spouse.721 The first installment was paid quickly, £0-15-0, "By Cash," on 8/9/28. But the second and last payment recorded, £0-5-0, on 5/28/29, "By Cash paid by his [next] Wife," still left a considerable balance of £0-9-0 remaining.722 Whatever Way's devotion to the memory of his first wife the year before, it apparently did not keep him from marrying soon after or from failing to settle the balance due on her "Redged Cofin."

But, perhaps Way couldn't afford to settle up. As tight-fisted as Head appears on occasion, even to including a charge of two pence, "To 2 Cofin Screws," in the account of the wealthy Alexander Wooddrop, he may have been generous to those who could not afford to pay, especially under the trying circumstances of a wife's death. After Joseph Hooper, "a Shomaker," was debited a modest £0-12-0, "To his wives Cofin," on 7/28/38, the only credit shown was an incomplete one, a month later, on 8/14/38, £0-7-0, "By a payer of shoues."723 Head may simply have not pressed payment.

Unlike cradles, the prices of coffins varied greatly, according to size, as well as material. In this respect they were unlike cradles, which Head could price more or less equally, as dimensions would be closer to one another, even for the one "Large Cradle." The least expensive, non-child size coffins were probably of pine. Head describes only two pine coffins. The cheaper was debited to Joseph Elger, on 9/19/22, at £0-15-0, as "To a pin[e] Cofin."724 More unusual was the entry, "To: a Pine Cofin Blact [blacked]," to Charles Hansly, on 2/30/23, at £0-16-0.725 Was the coffin blackened to make it appear more like a darker, more expensive wood, like walnut? But the entries to blackened coffins for servants, including a Negro woman, suggest the possibility of a different conclusion. Perhaps the color had something to so with the religion or skin color of the deceased. Thus, William Coats, on 9/15/27, was charged £0-16-0, "To a Blak Cofin made By his Order for his man."726 James Steel, on 12/5/30, was debited £0-16-0, "To his nagro woomans Cofin Blaked."727 Blacks were "buried in a particular place out of town," rather than churchyards or in the other out of town burial places reserved for Quakers, the English church, the "Newlights," and "Germans of the reformed religion."728

On 11/4/36, James Steel paid £2-0-0 "To his man Tobiases Cofin," for whom Steel must have held great affection to have paid so much. Tobias may have met an untimely death. The absence of a finely-dressed, "Indented Servant Man, named Tobias Shewen, aged about 23 Years," had been advertised by Steel several months earlier.729 Presumably, he is the same person.

The most expensive coffins often came ridged. This meant that their tops were not flat but came to a point like the top ridge of an "a-frame" roof. On 11/20/34, George Hawell [Howell?] paid £2-10-0, "To his Wifes ridgd Cofin."730 Thomas Redman's "Childs redged Cofin walnut," on 9/8/37, cost £0-18-0. Altogether, five ridged coffins were sold by Head.731

If not the most expensive, at £1-0-0, the entry for the coffin ordered by Caleb Ransted [Ranstead], on 7/17/29, was certainly the most descriptive and unusual: "To a Cofin for his Child 3 foot and Three Inches Long With Chandler."732 The "Chandler" was not a chandelier, but probably some form of candleholder or sconce. If as a light source for pre-interment viewing, this would be extremely important, as open casket viewings have hitherto not been recognized as having occurred in this period.733

Head sold a total of six coffins described as "walnut," and probably more.734 Unfortunately, the wide variance in pricing makes difficult their comparison with coffins of unidentified woods. The only other designated woods were the two in pine and the cedar one for Edgell's child. No mahogany coffins were listed. These would become de rigeur for the elite later in the century, as may be seen from the numerous entries for them from 1779 onward, in the daybooks of Philadelphia cabinetmaker David Evans.735

Nothing so extravagant housed the last remains of Head's clients and their families. Apart from sometimes being "ridged" or walnut, Head's coffins also may have had handles. While no coffins are so described, Head carried coffin handles in inventory. His debit transactions list a number of transactions, in the early 1720s, debiting "Cofin handles" and "Cofin Screws,"736 but only to individuals to whom no coffins were sold.737 Handles may not have been separately noted in the transactions with those individuals who bought coffins as the handles may have been included in Head's price for the coffin. While the account book does not disclose from whom such early coffin hardware was bought, it does identify his suppliers for a later period. On 1/3/37, Head credited the account of Stephen Paiten £1-1-0, "By 2 dosen of Cofin handles," and £0-9-0, for an equal number of "Iron Bolts," presumably for affixing the handles to the coffins.738 A decade later, on 10/19/47, the account of Thomas Maul [Maule] was credited £0-2-6, "By - 3 payer Cofin handles."739

XI. Conclusion.

Every nation, when sufficiently intellectual, has its golden and heroic ages; and the due contemplation of these relics of our antiquities presents the proper occasion for forming ours. These thoughts, elicited by the occasion, form the proper apology for whatever else we may offer to public notice in this way. There is a generation to come who will be grateful for such notices.John Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia740

APS home |

Bulletin home |

Issue table of contents |