3. Furniture Hardware.

Head both bought and sold vast quantities of nails. His earliest purchase was "To : 6 pound of nails," on 11/24/20, for which he credited Joseph Masters £0-4-6. That was part of 137 pounds of nails he bought from Masters between that date and 3/5/24.

286 Alexander Wooddrop was also an early large supplier. His nails and tacks, however, were priced per thousand pieces and not by the pound.

287 On 4/11/21, Wooddrop sold Head "1 m [1,000] nails d/2 [two penny nails]," at £2-2-5; and "5 m [5,000] - Larg Taks," at £0-8-4; and "6 m [thousand] - d/2 Brads [two penny brads]."

288 The last order credited, from Thomas Maul [Maule], on 11/9/47, at £3-3-3, was "By - 47 1/2 pound of nails."

289 Head, in turn, sold nails by the pound and, in one instance, by "a Bage [bag]."

290 Among the types of nails sold by Head were the "10 pond [pound] : hobd nails [hobnails], debited to Richard Luis [Lewis], at £0-5-0, on 7/23/21.

291

Not all of these nails were meant for use in furniture. Some were clearly for construction, such as the "28 pound of Larth [lath] nails," which Head bought from George Kellay.292 Head sold lath nails to brickmaker John Coats, in 1736, together with " 152 foot of oke scantlen [oak scantling]," and eight bushels of lime, obviously for a lathwork job.293

Head's earliest purchases of locks were the "Till Loks," of which he obtained significant quantities. Five dozen of them were bought from Alexander Wooddrop, on 4/11/21, apparently in two sizes. The cheaper, and perhaps smaller, ones were the "2 dosen," at £0-13-0. The slightly more costly were the "3 dosen," at £1-2-6.294 Wooddrop was an associate of Thomas Rutter (d. 1730), the "father of the iron industry in Pennsylvania.295 Cheaper till locks were also purchased from Jon [John] Copson, on 10/14/23, at £0-3-0, described as "To : 24 Loks plain Till."296 What Head meant by "plain" is unclear. Also, he gave no further description of the others. Head appears not to have sold any of his till locks in bulk until late in his career. On 8/1/45, Thomas Maule was debited £1-0-0, "To - 2 dosen of Till Loks." Maule also was debited £1-13-0, on 3/1/47, "To - 28 drawer loks and som Kies [keys]."297 As by this period any furniture sales had ceased to be recorded, he may no longer have had a need to stock so many till and drawer locks.

Most of the undescribed locks which Head purchased were at a shilling apiece.298 They were cheaper by the dozen.299 Edmund Woolley's "6 Loks", debited at £0-6-0, on 5/23/23, were probably for the £10-0-0 "Chest of drawers & Table Charytrewood" he purchased on that same date.300 Without seeing those two pieces, however, it is impossible to know on which drawers these locks were mounted. By comparison, the "Chest of drawers and a Chamber Table," which by tradition were made for the marriage of Caspar Wistar and Catherine Johnson, and may be the ones debited to his account, on 4/14/26, have key holes in their hardware to accommodate four locks. Three are on the three large drawers of the high chest's three-over-three drawer configuration. The fourth is on the central of the three drawers of the dressing table.301

James Cooper was debited only £0-3-0, "To 3 Loks & 3 scuchens [escutcheons] & puten [putting them] on."302 These were thus cheaper locks than those supplied Woolley. A cupboard lock was slightly more expensive, as Head charged Edward Williams, £0-1-6, "To a Lok for a Coberd." Thomas Canby was debited £2-10-0, "To an oval Table with two Loks." Josier [Josiah] Foster was debited £3-2-0, "To a Chest of Drawers & a Loke." That was probably for one of the standard £3-0-0 chests with the extra two shillings for the lock. A "Chest Lok" cost Maule £0-2-0.303 As this is twice as much as the shilling locks which accompanied Woolley's chest and chamber table, the locks for Foster and Maule may have been something either larger or more elaborate.

There was good reason to have locks on cupboards and table drawers and other places where food was kept. Attempts to domesticate the raccoon had failed in one vital respect: "[I]t is impossible to make it leave off stealing....Sugar and other sweet things must be carefully hidden from it, for if the chests and boxes are not always locked up, it gets into them, eats the sugar, and licks up the treacle with its paws...."304

Some locks were even more costly, and may therefore have been meant for other purposes than mounting on furniture. Mary Davis sold Head "2 : Loks," at £0-11-0, and another two, probably smaller or simpler, at £0-10-0. Head also credited Isaac Shute £0-1-6, "To a Hors Loke," on 7/15/25.305 Even second-hand locks had some value. Head appears to have given Richard Blakham £0-2-6 credit for "an ould lok, on 7/8/44.306

Not every lock may have needed a key. Head sometimes may be using the term lock to mean fastener. Thus, the £0-2-6, which Abram Cox was charged, on 7/9/22, "To 8 loks & 2 scrws [bed bolts?]," may have been to secure the "Comperst Rods [arched tester]" to the "Cornish" and "Badstad," which he had ordered from Head that same date. Other types of fasteners included the "Six Staples," which cost Samuel Asp £0-1-6, on 4/8/30, the same date he purchased his "Badstad" and "Comparst Curtin Road [arched curtain tester] and 2 scrues [bed bolts?]."307

Only one locksmith is identified by Head. "Ladwik Sipel the Dutch Loksmith" appears to have done no work for Head, as no credits appear on the contra page of his account. Head, however, supplied Sipel. In addition to 42 bushels of lime, Sipel was debited £4-17-0, on 1/30/43, "To - 3=0=26 pound of Iron;" and £3-7-6, on 2/15/43, "To - 2=1=0 pound of Iron."308 The first iron order was gotten through John Leacock, whose account was credited in the same amount, on the same date, for a like quantity.309 John Ludwick Seipel advertised the sale of his "Commodious brick house, conveniently built, with other additional tenements thereon, between William Branson's and John Kampher's, in the Northern Liberties of this city, containing in front 20 feet and 120 feet deep, at the lock smith's sign, in Second Street...."310

Head used and dealt in a variety of hinges. He purchased pairs of "Buts [butt hinges]" from William Branson, paying £0-6-0, "To 6 payr Buts," and £0-10-0, "To on[e] dosen small Buts."311 Branson's iron works were at Reading Furnace.312 Among the joint hinges he bought were "3 payer Bras Joynts," from Andrew Duche [Duché], at £0-6-0. Clockmaker William Stretch was credited £0-3-6, "To a payer Clock Cas Joynts," the same price Head later credited Peter Stretch, "By a payer of Inges." Hinges with hooks were bought in large quantities. Abraham Kinzing, for example, was credited £0-4-7, "By 5 pound and 1/2 of hooks & Inges."313

|

Chalfant Collection |

|

Fig. 13: Miniature chest of drawers on five legs with peened drops and an escutcheon

Formerly in the collection of the late Robert Simpson Stuart |

The earliest recorded hardware pulls acquired by Head were the "7 dosen & 1/2 drops & scuchens [escutcheons]," for which he credited William Branson £1-8-1 1/2, on 9/30/21.

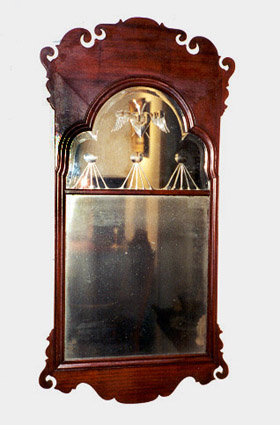

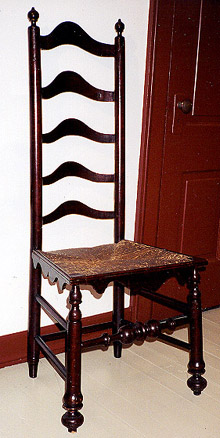

314 Drops and escutcheons were a popular choice of hardware on the earliest Philadelphia furniture, such as those shown on the drawers of a trumpet-turned leg, cross stretchered dressing table [figs. 12, 12a], and a miniature chest of drawers on frame [fig. 13]. The drops were secured with a a cotter pin, inserted through a hole in the escutcheon and then peened onto the back of the drawer front. Contemporaneous with drops were handles, which eventually supplanted them. Jon [John] Copson, on 4/6/24, was credited £0-2-4, "To on dosen scuchens;" and £0-8-0, "To: 2 Dosen handles."

315 At first, the handles, too, were peened through the drawer fronts with cotter pins. At some point, cotter pins disappeared in favor of the sides of the handles fitting into threaded posts, which could be inserted through holes in the drawer fronts, and be held fast by nuts.

316 Perhaps, Head may have been referring to that kind, when he recorded selling "2 Screu Handles," to Bangman Rods [Benjamin Rhoads?], on 10/18/20, at £0-1-0.

317

Indicative of the high activity of Head's cabinetmaking business was his hardware-buying binge in 1726. Pewterer Simond Hagal or Edgal [Simon Edgell] was credited "To : 4 : dosen & 1/2 of drops and scuchens" [4/11/26, £0-13-6]; "To : 3 dosen of drops & scuchens" [4/14/26, £0-15-0]; "To - 27 drops and scuchens" [4/18/26, £0-10-1 1/2];" and "To 4 dosen Cofen scrues" [8/14/26, £0-4-0]."318 Thus, in addition to his pewter business, Edgell seems to also have had a thriving business in decorative brasses and other hardware for furniture. This makes sense, given that Edgell left 1,183 pounds of brass moulds.319 John Whit & Abram Tailor [Taylor?] were credited "To : six dosen of drops [4/12/26, £0-15-0]." Boulah [Beulah] Coates was credited "To : 9 : dosen of handles & scuchens" [5/2/26, £2-0-6], in what appears to be the last order for this type of hardware that Head placed. Beulah Coates (d. 1741), the widow of Thomas Coates (d. 1719), was said to have been a "woman of considerable business ability."320

On 7/15/27, Head sold Thomas Linley, "Ten drops and 5 scuchens," at £0-5-0.321 Thereafter, the only pulls which might have used for furniture, that Head recorded buying, were knobs. On 1/16/32, he credited £1-19-0, to Andrew Duche [Duché], "By - 19 dosen and 1/2 of Bras knobs."322 Head's last sale of pulls, to Thomas Maule, on 8/1/45, at £0-7-0, "To - 2 dosen of handles & scuchons," as with his other quantity sales of hardware to Maule, may indicate that Head had exited the cabinetmaking business.323

Illustrative of the tricky footing on which any interpretation of Head's phonetic spellings often stand, is his 8/30/31 credit entry of £0-0-10, to Lawrence Boore's account, "By Buter & scuches." As it is unlikely that Head was ordering his escutcheons slathered in butter, an alternate translation yields a more palatable result: "butterscotches."324